I live by a creek, Plaster Creek, in a former oak grove in West Michigan.

Every so often, I walk down a busy street in my part of Grand Rapids, past rows of brick and vinyl-sided houses, a church, and two schools, and turn onto a path that takes me to the sound of rushing water.

The creek is difficult to find unless you know where to look. Parts of its arms have long been buried in tunnels beneath the asphalt to make way for busy streets and big-box stores. Each time I reach it, my heartbeat quickens, as though I’m hearing the voice of a friend.

This friend is deathly ill. Its 25.9 miles of length is overrun with toxic substances, thermal pollution, and E. coli contamination—sometimes orders of magnitude higher than what is safe. When it rains, flash floods eat away at its jagged banks. The neglected undergrowth is caked in layers of old garbage, and plastic bags are caught in the branches of overhanging trees—many of which lie tipped on their sides, roots exposed. A sewage smell hangs in the air.

One early winter day last year, I arrived at the creek to find two rotting pumpkins sticking out of the water like orange sores. Human contact with the water is prohibited, so I simply stood on the bridge for a few moments.

Looking at the overwhelming list of creation care priorities—disappearing rainforests and glaciers, species on the brink of extinction, extreme weather patterns, the warming ocean—it would be easy to wonder why one creek should matter. But when I stand on the bridge over Plaster Creek, I am reminded that the story of humankind began near running waters like this one, in Eden, where Adam and Eve were formed in its heart and tasked with tending it.

Only after the Fall was humanity separated from the garden and its life, set at odds against each other and the earth. “Cursed is the ground because of you,” God says to Adam in Genesis 3 before he banishes man and wife, setting “a flaming sword flashing back and forth to guard the way to the tree of life” (vv. 17, 24). Our rejection of God broke our relationship not only with him but with his creation. Millennia later, the proof is in the creek.

It’s true—gloriously so—that we are not condemned to remain in brokenness forever. We celebrate Christ’s incarnation in this season, and all around us are reminders that a return to God’s Edenic intent is nigh.

But that time has not yet come in full. We are still singing, “O come, O come, Emmanuel,” and all of creation joins us in our longing for the day when threat and decay will be no more and even the smallest creeks will be made new.

Two hundred years ago, Plaster Creek was called Ken-O-Sha (“water of the walleye”) by the Ottawa people who lived along its banks.

The Ottawa had a tenuous relationship with European settlers in the young city, as treaties were increasingly driving the Indigenous peoples farther west. Mayor Charles Belknap recounted a disagreement that happened during this time between an Ottawa elder named Mack-a-de-penessy (Chief Blackbird) and a Christian missionary.

Chief Blackbird said the best place to encounter God was outdoors; he couldn’t see why the missionary kept trying to convince his tribesmen to go inside a building. So the chief invited the missionary to come with him in his canoe to where the Ken-O-Sha met the Grand River. There, an impressive waterfall cascaded over a huge orange rock. This, the chief said, was where he and his people met the divine.

The missionary sent a sample of that outcropping to Detroit for analysis. The results confirmed that the rock was gypsum, a valuable resource used as a fertilizer and for making plaster. Until this time, plaster had been imported from as far away as Nova Scotia. But now it could be mined locally.

The first plaster mill in West Michigan opened on Chief Blackbird’s sacred spot in 1841. Not long after, Ken-O-Sha’s name was changed to Plaster Creek. By 1850, the company was mining 60 tons of gypsum a day, and by 1890, there were 13 mines in the area, shipping the resource as far away as California.

At the same time, the walleye fish that once teemed in the creek vanished, along with the Ottawa and other Indigenous groups. In 1910, one local, Charles W. Garfield, wrote, “Instead of being the beautiful even-flowing stream throughout the year, as in my childhood, [Plaster Creek] is now a most fitful affair. … A near sighted utilitarianism has snatched it away.”

As Grand Rapids moved on from gypsum mining to furniture making, the creek became a dumping ground for toxic waste. The poor water quality meant humans were not allowed to touch it, much less wade in it, while the nonhuman life in and around the creek suffered, including the endangered snuffbox mussel, sunfish, and salmon, as well as minks, herons, deer, and foxes. People growing up in the 1960s recalled that the creek would sometimes be bright red, sometimes green, from various paints poured into it, and there was always the lingering scent of lacquer.

By the early 2000s, Plaster Creek had become West Michigan’s most polluted waterway.

The creek in my neighborhood is only one example in a national epidemic. Today, nearly half of all rivers and streams and more than a third of all lakes in the US are so polluted that swimming and fishing in them are banned. A 2021 Gallup poll found that the pollution of drinking water—more than global warming, air pollution, or the extinction of plant and animal species—is the No. 1 environmental concern among American adults.

In 1975, Annie Dillard won the Pulitzer Prize for her book Pilgrim at Tinker Creek, a poetic chronicling of her creek-side year in Virginia’s Blue Ridge Mountains. But even Dillard’s Tinker Creek was not immune to the effects of industrialization and pollution.

In 2012, Virginia was listed as the second-worst state in the country for toxic chemical dumping in waterways, with more than 18 million pounds of chemicals like arsenic, mercury, and benzene released annually into streams. In 2017, a chemical spill in Tinker Creek killed 40,000 fish, and in 2020, petroleum-based contaminants created a malodorous sheen on the water, resulting in a ban on human contact.

If Dillard had been writing her book in the 21st century, she may not even have been able to touch it.

Waterways like Plaster Creek are small veins in a huge system, but what happens in them has large-scale consequences. Plaster Creek empties into the Grand River, and the Grand River flows into Lake Michigan, connected to the other Great Lakes. Together, the lakes comprise nearly one-fifth of the planet’s total fresh water supply.

There is a long tradition, especially in America, of seeing the ideal state of nature as pristine and removed from the bustle of civilization, what some have called the “wilderness myth.” When Yosemite National Park was promoted to the American public, for example, it was portrayed as wild, unspoiled lands, intentionally wiped clean of traces of civilization. In truth, early photographers like Ansel Adams “assiduously avoided photographing any of the local Miwok who were rarely out of his sight as he worked Yosemite Valley,” noted journalist Mark Dowie.

Environmental historians like William Cronon have said that seeing nature in this idyllic way sets up a false, mutually exclusive dichotomy between nature and people, leading to neglect and exploitation. But there’s a theological dimension here too: The wilderness myth is not just wrong; it is unbiblical.

When God made the world, he did not put humans in one place and Eden in another. He formed man from the dust of the garden and said it was very good. And even after the Fall, when the Son of Man came to earth, he did not cut humans out of the picture. He united himself with us as a helpless baby, as a man who wept and ate and slept and prayed, as a man who died. There were no rose-tinted glasses or carefully filtered photographs when Jesus shouldered the full weight of creation’s sin and decay.

“In Jesus, God dwelt among us, taking on flesh and entering into creation, participating in the very life and matter of the world,” states Christian environmental group A Rocha International’s Commitment to Creation Care. And through Jesus’ death, “God defeated the power of sin and death and accomplished the reconciliation of all things—human and nonhuman—giving hope for all that is broken and spoiled, and eternal life to all who receive Him.”

In Christ, humanity—and all of creation—is not mythologized or cut out of a picture but redeemed. In Christ, God looks at all he has made and says once more that it is good.

And just as at the dawn of creation, his words have the power to enact what they pronounce.

One snowy Sunday afternoon, 40 members of my church donned work gloves and winter coats to pick up trash along two sections of Plaster Creek. Before heading out, my husband, the pastor, read from Our World Belongs to God, our denomination’s hymn-like articulation of Reformed confessions:

As followers of Jesus Christ,

living in this world—

which some seek to control,

and others view with despair—

we declare with joy and trust:

Our world belongs to God!

With this proclamation echoing in our ears, we reached the creek. The kids in our group treated the cleanup like a treasure hunt, comparing who could get the grossest find—my 9-year-old son proudly held up a dirty diaper while his friend boasted about a moldy bottle. On my way to drop off some glass shards in the sharps pile we had demarcated with a circle of twigs, a young woman in our group silently pointed out a person sleeping in the ledge beneath the bridge, wrapped in what looked like a large plastic sheet.

At the end of an hour, we filled the entire back of a van with stuffed trash bags. The group at the other section filled a trailer and a pickup truck. I overheard someone remarking in the parking lot, “We could have done this for four more hours and still picked up more trash.” Everyone’s cheeks were red in the blustery wind, and we blinked snowflakes out of our eyelashes.

In the early 2000s, Plaster Creek wasn’t on the radar of churches like ours, and no Christian organizations advocated on its behalf. That changed when Gail Heffner, then the director of community engagement for Calvin College (now Calvin University), together with Dave Warners, a Calvin ecology and biology professor, heard that the Plaster Creek watershed was “in really bad shape.”

Watersheds—areas of land that channel precipitation and runoff into a common body of water—are connected, like bowls that flow into larger bowls. More importantly, every human on earth lives in one. For Heffner and Warners, Plaster Creek wasn’t just any watershed—it was the one the college is located in.

“We started going to some community meetings just to listen, to find out what they were telling us,” Heffner said, shifting in her seat in the small conference room at Calvin’s Science Building where we met. “At that point, we didn’t know a lot about the Plaster Creek watershed.”

Most of the pollution in Plaster Creek today is not because of hazardous waste dumping like it was in earlier decades. That was curtailed by national laws like the Clean Water Act of 1972. Heffner and Warners learned the pollution was mostly caused by agricultural runoff from upstream areas south of Grand Rapids. When it rained, stormwater washed huge amounts of excess fertilizer in the form of high phosphorus and nitrogen content into the creek, which became increasingly polluted with livestock excrement, runoff sediments, garbage, and oils as it moved downstream into poorer urban communities like ours before joining the Grand River.

The upstream agricultural community was also made up of many Christians. In 2008, a senior staff member of the Michigan Department of Environmental Quality turned to Warners and Heffner for help. “They said, ‘Look, there are Christians upstream who are refusing to listen to us,’” Heffner recalled. “‘But maybe they’ll listen to you.’”

Heffner and Warners launched Plaster Creek Stewards (PCS) shortly thereafter in 2009 as one of the country’s only Christian watershed programs and one of the few connected to a university. But they quickly found that few believers were interested in the health of the creek. In fact, some directly opposed the work of PCS, going so far as to send physically threatening messages to its staff.

One way to help decrease pollution in waterways like Plaster Creek is to slow down the flow of water coming into it in the first place. PCS thus focuses on installing porous parking lots, rain gardens, bioswales, retention basins, and floodplains. When PCS tried to install a large floodplain at a local park, however, widely circulating misinformation led the community to believe that their beloved Dutton Shadyside Park was about to be ruined.

“We learned the hard way that public projects require intensive listening to and partnering with the community,” Warners said.

After two years of wading through an appeal process in courts, PCS received a permit to proceed, with significant adjustments to honor some of the concerns expressed by the park users, like preserving several historical trees, keeping a green space for an annual dog show, and adding a new pedestrian bridge.

When construction finally began, hundreds of local students, churches, businesses, and neighbors came to help.

“In its consciousness, ours is an upland society,” essayist and poet Wendell Berry notes. Indeed, we are unaware of the outcomes of our consumptions and practices. “The ruin of watersheds, and what that involves and means, is little considered.”

Consciousness stirs when creation care is no longer an abstract concept but actual dirt on our hands. At our church’s cleanup event, my son, his bag of litter slung over one shoulder, looked up at me and said, “Mama, this is our creek, right?” An act as simple as picking up a soiled candy wrapper sends a message: I care about the cleanliness of this place. I care about it like it’s my own.

Churches, including ours, have found that this kind of hands-on care also resonates with the communities they’re trying to reach.

“We find that a lot of folks, [when] we’d say, ‘Come to our church picnic,’ they’d say, ‘No, thanks,’” shared one man interviewed by Heffner and Warners in their book, Reconciliation in a Michigan Watershed: Restoring Ken-O-Sha. But when neighbors would find out the church was going to clean up the creek, he said they’d respond, “‘Can I come with you?’ And then it is something that we are doing alongside our neighbors, [where] we get to illustrate God’s love for creation, and his love for this neighborhood.”

Restoring the creek is slow work. Contaminants in moving bodies of water are notoriously hard to measure due to their erratic fluctuations. “It’s taken several hundred years for the creek to get this bad,” Warners said. “It’s going to probably take several decades of concerted effort to be able to get it better.”

Some of the people most passionate about PCS’s work are young people. For many students, learning, research, and experimentation extend beyond academics. They’re a tangible act of caring for the earth among a generation where more than 4 in 10 say we’ve hit “the point of no return” with the environment, according to a 2021 Deloitte survey.

Engineering students at Calvin have built a hydraulic model of a section of the creek to aid research. History students have studied land-use patterns over time in the watershed. One year, a taxonomy group found beak grass, the only known patch of the endangered species in the county.

Warners recalls how one student came to his office firing off questions about PCS’s work before saying tearfully, “It’s been hard to have hope lately. But what you’re doing for this creek is beautiful.”

When we are children, our backyards and parks are our wildernesses—every tree and bush aflame with glory. I remember my siblings and I spending a summer hunched under the tent-like canopy of a pine tree, only several feet from the sidewalk, imagining that we were in a forest. In the winter, we tried our best to walk without a sound across the snow, exploring our tiny plot of land in an Ohio suburb. New discoveries—the long icicles on the edges of the house, the tracks of a creature leading into the brush—were as mysterious as finding a lamppost in the middle of a snowy wood.

Childlike wonder is something we as adults must relearn this side of the Resurrection: a re-visioning of nature as our home and our keeping, as something more like Eden, where creation flourished in the care of humankind.

Here in southeast Grand Rapids, that happens when I look up into the massive crown of the ancient oak tree in our yard and when I trace the hairline fractures in our old plaster walls. It happens each time I walk to our neighborhood creek and recall the vision in Revelation and what it means for creeks like this one.

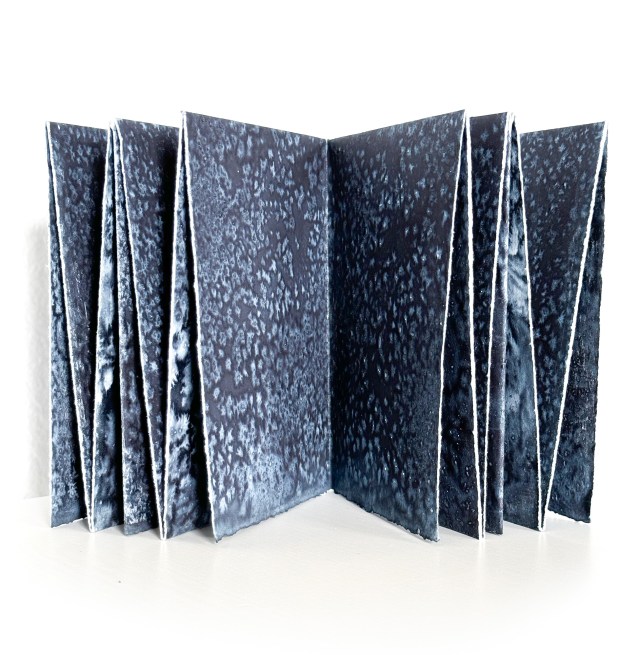

Courtesy of Gail Gunst Heffner

Courtesy of Gail Gunst HeffnerIt is a vision toward which all of history is pointing: a re-peopling of Eden, not as an untouched wilderness but as a garden-city through which runs the river of life, “clear as crystal” and “flowing from the throne of God” (Rev. 22:1). Along its banks will be planted the tree of life, the apostle John tells us, whose leaves will be used for the healing of the nations (v. 2).

That healing is not an abstract concept for nature “out there” and temporally far away. It is a promise for our own backyards, our neighborhood parks, our creeks—every place where we walk, day in and day out.

I have faith that when the new creation comes, the healing leaves will be brought to Plaster Creek too; that children, including my own, will be able to splash in its waters without fear. On that day, even the impossibly high cost of forgiveness for all that was wrought—the violent expulsion of the Ottawa, the exploiting of land and water, the conflicts that rend the body of Christ—will be paid for in full, even to overflowing.

Even now, there are glimmers of newness in every direction. Warners says that, in the spring, when new species of butterflies or birds visit native gardens they’ve placed in the neighborhoods alongside the creek, it’s like the triangle of God, humankind, and creation is restored. It’s then that he can keep hoping and working toward the day when Plaster Creek will be called “water of the walleye” again.

Meanwhile, each year in our neighborhood, I see more and more houses transforming the strips of grass between sidewalk and curb into rain gardens. Last summer, hundreds of community members painted a mural along a neglected 2,000-square-foot stretch of cement wall beside the creek. There are reports that sturgeon, another species of fish that disappeared, are returning to the Grand River.

On our neighborhood Facebook page, there’s a long thread about how we can care for those without homes camping near the creek, especially as winter draws near. Next summer, like every summer we’ve lived here, teams of high school students with PCS will walk laughing down the sidewalk outside my window with shovels in hand, off to sow more seedlings. People at our church are asking when the next cleanup day will be—pilgrims, all of us, beside Plaster Creek, waiting as we listen for resurrection to be spoken over every rivulet.

Sara Kyoungah White is an editor at Christianity Today.