"In order that men might have knowledge of God, free of doubt and uncertainty, it was necessary for divine truth to be delivered to them by way of faith, being told to them as it were, by God himself who cannot lie."

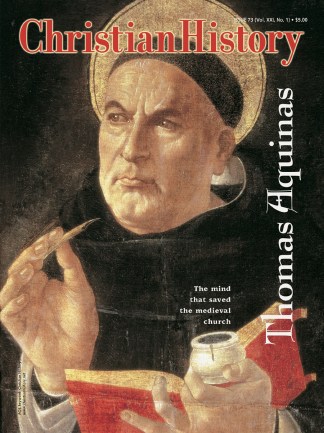

No one claimed Thomas Aquinas got famous on his looks. He was colossally fat, suffered from edema (dropsy), and one huge eye dwarfed his other. Nor was he a particularly dynamic, charismatic figure. Introspective and silent most of the time, when he did speak, it was often completely unrelated to the conversation. His classmates in college called him "the dumb ox." Today, recognized as the greatest theologian of the Middle Ages, he is called "the doctor of angels."

Timeline |

|

|

1208 |

Francis of Assisi renounces wealth |

|

1215 |

Magna Carta |

|

1220 |

Dominican Order established |

|

1225 |

Thomas Aquinas born |

|

1274 |

Thomas Aquinas dies |

|

1302 |

Unam Sanctam proclaims papal supremacy |

Temptations of a future theologian

He was born in an Italian castle to "Count Lundulf" of Aquino (though he was probably not a count) and Lundulf's wife, Theodora. At age 5, the pudgy boy was sent to the school at the nearby monastery of Monte Cassino (a community founded by Benedict seven centuries earlier). At age 14, Thomas went to the University of Naples, where his Dominican teacher so impressed him that Thomas decided he, too, would join the new, study-oriented Dominican order.

His family fiercely opposed the decision (apparently wanting him to become an influential and financially secure abbot or archbishop rather than take a friar's vow of poverty). Thomas's brothers kidnapped him and confined him for 15 months; his family tempted him with a prostitute and an offer to buy him the post of archbishop of Naples.

All attempts failed, and Thomas went to Paris, medieval Europe's center of theological study. While there he fell under the spell of the famous teacher Albert the Great.

Wrestling with reason

In medieval Europe, all learning took place under the eye of the church, and theology reigned supreme in the sciences. Still, non-Christian philosophers like Aristotle the Greek, Averroes the Muslim, and Maimonides the Jew were studied alongside the Bible. Scholars were especially fascinated by Aristotle, whose works had been unknown in Europe for centuries. He seemed to have explained the entire universe, not by using Scripture but by his powers of observation and reason.

This emphasis on reason threatened to undermine traditional Christian beliefs. Christians had believed knowledge could come only through God's revelation, that only those to whom God chose to reveal his truths could understand the universe. How could this be squared with the obvious knowledge taught by these newly discovered philosophies?

Thomas wanted to explore this issue, and he determined to extract from Aristotle's writings what was acceptable to Christianity.

His thoughts consumed him. According to one story, he was dining with Louis IX of France (later "Saint" Louis), but while others engaged in conversation, he stared off into the distance lost in thought. Suddenly, he slammed down his fist on the table and exclaimed, "Ah! There's an argument that will destroy the Manichees!"

At the beginning of his massive Summa Theologica (or "A summation of theological knowledge"), Thomas stated, "In sacred theology, all things are treated from the standpoint of God." Thomas proceeded to distinguish between philosophy and theology, and between reason and revelation, though he emphasized that these did not contradict each other. Both are fountains of knowledge; both come from God.

Reason, said Thomas (following Aristotle), is based on sensory data—what we can see, feel, hear, smell, and touch. Revelation is based on more. While reason can lead us to believe in God—something that other theologians had already proposed—only revelation can show us God as he really is, the triune God of the Bible.

"In order that men might have knowledge of God, free of doubt and uncertainty," he wrote, "it was necessary for divine truth to be delivered to them by way of faith, being told to them as it were, by God himself who cannot lie."

In other words, someone looking at nature could tell that an intelligent creator exists. But that person would have no idea whether the creator was good or if he might work in history. Furthermore, though a person apart from Christianity can practice certain "natural virtues," only a believer can practice faith, hope, and love, the truly Christian virtues.

Volumes of straw

Thomas's writings (including the Summa Contra Gentiles, a manual for missionaries to the Muslims, which also contains several hymns) were attacked before and after his death. In 1277, the archbishop of Paris tried to have Thomas formally condemned, but the Roman Curia put a stop to the movement. Though Thomas was canonized in 1325, it took another 200 years before his teaching was hailed as preeminent and a chief bulwark against Protestantism. Four years after the Council of Trent, in which his writings play a prominent part, Thomas was declared a doctor of the church.

In 1879, the papal bull Aeterni Patris endorsed Thomism (Aquinas's theology) as an authentic expression of doctrine and said it should be studied by all students of theology. Today both Protestant and Catholic scholars draw upon his writings.

Thomas, however, would not necessarily be pleased. Toward the end of his life, he had a vision that forced him to drop his pen. Though he had experienced visions for years, this was something different. His secretary begged him to start writing again, but Aquinas replied, "I cannot. Such things have been revealed to me that what I have written seems but straw."

His Summa Theologica, one of the most influential writings of the Christian church, was left unfinished when he died three months later.

Corresponding Issue