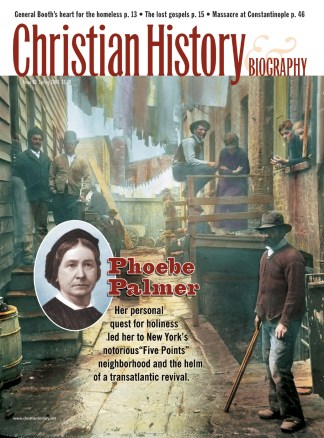

In January of 1857 the editors of a national magazine published a portrait of Phoebe Palmer (facing page). Being honest men, they admitted that the woman herself was neither as young nor as pretty as the picture made her appear. They did say, however, that she was smarter than she looked. Palmer was probably not offended by their comments. She was friends with the editors and shared their Wesleyan heritage of plain speaking. Anyway, physical beauty was unimportant to her; what mattered was the beauty of the soul. She wanted “the beauty of holiness” that empowered one to live a well-balanced, useful life.

During her life (1807-1874) Palmer spoke to over 100,000 people about Jesus and sparked a revival that brought nearly a million people into the church. Her influential theology paved the way for such modern holiness denominations as the Church of the Nazarene and the Church of God (Anderson, Indiana), and for Pentecostalism as well.

Being a well-known female speaker made her a feminist, though what would today be considered a “conservative” one: she championed the right and duty of women to speak publicly for the Lord. But Palmer did more than talk about Jesus. She put his love into action in New York City’s worst slum, pioneering a new kind of incarnational philanthropy.

Youthful yearning

The heart-felt Methodism in which Phoebe was raised insisted on emphatically emotional experiences of conversion and sanctification. A bright, intense girl, Phoebe could never feel she had attained this. At the age of 13, she did have a vision of Jesus coming to enfold her in his arms and bidding her “be of good cheer.” Yet despite this and other experiences, she continued through her teens to wrestle with the Methodist emphasis on emotional experience.

Distracted by the comforts and the social duties (for example the perpetual “visiting”) of middle-class life, Phoebe yearned for a steady consciousness of her redemption and union with Christ—in short, for the Wesleyan sanctification experience that would overcome her constant failure to live for God, replacing it with “perfect love” towards God.

Consecrated through crisis

After ten years of marriage and the birth of three children, Palmer’s yearning was intensified by a shattering experience. On July 29, 1836, Phoebe rocked her beloved 11-month-old daughter Eliza to sleep and placed her in her crib before retiring to her own room. Soon after, Phoebe heard screaming from the nursery and came running. A careless helper had tried to refill an oil lamp without putting it out. When the flames shot up, she had thrown the lamp away from her. It had landed in the crib, splashing burning oil all over the child. Stricken, Phoebe cradled the infant in her arms. Within hours, Eliza was dead.

Phoebe paced the floor, filled with anger and grief. This was the third of her children to die in infancy. She cried out in anguish to God and heard an answer that, though it seems harsh, brought her comfort: God had taken her children because she had loved them too much and was spending too much time on them. “No other gods before me” was his command. At that moment, she resolved that she would surrender to God everything she held dear. She wrote in her diary: “Never before have I felt such a deadness to the world, and my affections so fixed on things above. God takes our treasures to heaven, that our hearts may be there also. And now I have resolved that the time I would have devoted to her [Eliza] shall be spent in work for Jesus.”

A year later, almost to the day, Phoebe Palmer at last received the longed-for experience of entire sanctification. On July 27, 1837 she wrote, “Last evening, between the hours of eight and nine, my heart was emptied of self, and cleansed of all idols, from all filthiness of the flesh and spirit, and I realized that I dwelt in God, and felt that he had become the portion of my soul, my ALL IN ALL.”

A four-fold ministry

In 1840, Palmer began presiding over the “Tuesday meetings for the promotion of holiness” started by her sister Sarah Lankford Palmer in the parlor of her New York home. Soon these meetings, with their strong emphasis on testifying to one’s experience with God, spread the holiness message across America.

The theology Palmer developed and presented in these meetings was a simplified and popularized version of John Wesley’s doctrine of Christian perfection. Her “shorter way” or “altar theology” taught that one attained sanctification through three simple steps: consecration, faith, and testimony. The believer has only to dedicate all time, talents, relationships, and goods to God; believe in his Bible promises; and then, after receiving the blessed gift of entire sanctification, tell the world about it at every opportunity. This emphasis on attainable sanctification made her the mother of the holiness movement.

As a revivalist, Palmer spoke in more than 300 camp meetings or revival services. In 1857 her preaching sparked the urban “prayer-meeting revival” that brought hundreds of thousands of converts into the American churches. In 1859 she and her husband followed the revival to the British Isles. While there Phoebe Palmer worked to reform British Christianity. Twice she wrote to Queen Victoria asking that the sovereign’s band not perform on Sunday. Once she refused to hold meetings in a church that allowed alcohol to be stored in its cellar. Despite these quirks, more than 20,000 of the Palmers’ hearers experienced salvation or sanctification. Dr. and Mrs. Palmer’s efforts were part of a movement of the Spirit that brought over a million people into the various churches in England, Ireland, Scotland, and Wales.

Palmer’s emphasis on holiness helped to remind Christians of their high calling when revivalism had flooded the church with people who were comfortable to live a merely social Christianity—holiness leaders would have said, were only “half converted.” She also civilized and systematized the methods of frontier Methodist revivalism, especially the Methodist emphasis on lay ministry. The famed evangelist Charles Grandison Finney had spoken of the role of the laity in revivals, but Palmer was the first to organize their labors effectively in a city-wide effort. Her emphasis on the role of the laity helped prepare laypeople to play a major role in urban revivalism. Palmer’s practice was one of the factors that transformed revivalism from Finney’s clergy-centered campaigns in small towns to Moody’s lay-oriented crusades in large cities.

Tongue of fire, arms of love

Where Palmer could not go in person, she went through her books and magazine. She wrote 18 books of practical theology, biography, and poetry. For 11 years she edited the Guide to Holiness and made it one of the most popular religious periodicals of the day. The Guide had an international audience with subscribers in Canada, the United Kingdom, Liberia, India, and Australia.

Just by preaching and writing, Phoebe Palmer promoted the cause of women’s rights. In addition she wrote a hefty and well-argued book defending women’s ministries, The Promise of the Father (1859), published again ten years later as the edited-down Tongue of Fire on The Daughters of the Lord; or, Questions in Relation to the Duty of the Christian Church in Regard to the Privileges of Her Female Membership. Arguing that the baptism of the Holy Spirit given at Pentecost was available to women as well as to men, Palmer said that the filling of the Spirit obligated both men and women to speak out for Jesus.

Not content to just speak and write, Palmer cared for people’s social and physical needs. She scoured New York’s slums for children for the Sunday school and took food, clothes, and medicine to needy families. With her husband, Walter (a doctor who often provided medical assistance free of charge to poor patients), she helped to establish a church in a poor neighborhood, and once she even paid a young mother to go to church with her. The woman was a cobbler and said she could not afford even two hours away from her bench. Palmer offered to replace that much of her wage, and the next Sunday church members were unsurprised to see Phoebe Palmer arrive for service with another new friend in tow.

Phoebe and Walter even, in the 1850s, adopted a teenager to help him follow Jesus. On a visit to a jail Phoebe discovered Leopold Soloman, a Jewish lad whose parents had disowned him when he became a Christian. Thrown out of his house, and with no means of support, he was arrested for vagrancy. Even after his fine was paid he was too young to be released with no place to go. Simply offering him a place to live would not satisfy the law, so the Palmers officially adopted him. (The boy’s parents later reclaimed him and persuaded him to forsake his Christianity, and the Palmers never heard from him again.)

Obviously the Palmers could not adopt everyone in need, so as a director of the Methodist Ladies’ Home Missionary Society, Phoebe agitated until the Society opened a settlement house in New York’s worst slum, the Five Points. This “frightening warren of brothels, low-grade dives, decayed tenements, street gangs,” as historian Paul Boyer describes it, was so dangerous that when Charles Dickens visited it, he took two tough policemen with him! But where Dickens feared to tread (calling it the hub of all that was “loathsome, drooping, and decayed”), Palmer went alone to show God’s love to the destitute.

Palmer realized that adopting individuals and visiting families would not solve the massive problem of urban poverty. The mission house at Five Points incarnated God’s love by allowing workers to live among the poor and by giving the poor a place to live as they took their first step out of poverty. Its pioneering work helped to break ground for other rescue missions and settlement houses over the next hundred years.

The freedom of a sanctified woman

Phoebe Palmer’s contributions to theology, revivalism, feminism, and humanitarianism mark her as one of the most influential American women in her century. Her achievement gives rise to the question: Where did she get her energy? Obviously, having servants helped to free her from the normal routine of caring for a family. Perhaps, however, the answer lies deeper.

Palmer knew the scriptural promise that her labor in the Lord was not in vain (1 Cor. 15:58). Because she was convinced she was entirely sanctified, she believed everything she did was a “labor in the Lord.” Thus she was encouraged to attempt great things for God, knowing that in an ultimate sense, she could never fail. She felt that God had promised to crown whatever she undertook with success. Armed with this confidence, she did not grow weary in well-doing.

It seems entire sanctification had the same effect in Palmer’s life that justification by faith had in Luther’s. In The Freedom of a Christian Luther argued that because Christians are justified by faith, they must not spend any energy trying to justify themselves. Freed from the impossible task of self-justification, they can give all the energy that used to go into scrupulous obedience and detailed confession in service of their neighbors.

In the same way, Phoebe Palmer’s doctrine of sanctification by faith freed enormous energies for the service of others. Since her “all was on the altar,” she knew God accepted and empowered her. The energy that had once gone into brooding about her spiritual state was now discharged in working for others.

Palmer, however, would have answered the question in another way. She asserted, “Holiness is power.” She believed that just as the Holy Spirit had energized the disciples after the day of Pentecost, so every Christian who receives the Spirit in entire sanctification will be similarly empowered. Her life, she felt, amply demonstrated this truth.

After Palmer died, tributes streamed in from many places. Robert Pearsall Smith said he knew of no other woman in the history of the church who had been so used of God to convert people and to build them up in holiness.

While Phoebe Palmer was well-known at her death, today she is almost unknown. But her obscurity would not irk her. In fact, she worried about the renown she enjoyed in her own life, feeling that such fame would detract from her heavenly reward. Like her hero, Susanna Wesley, she was “content to occupy a small space if God be glorified.”

Charles White is professor of Christian Thought and History at Spring Arbor University, Spring Arbor, Michigan.

Old forests, new meetings

No frontier-like shenanigans here. Just a genteel urban audience returning to nature to meet their God.In the 1840s, the Tuesday Meetings and holiness writings of Phoebe Palmer helped start the holiness revival. But the revival became a truly national phenomenon in 1867 and 1868. In 1867, the first camp meeting for the specific purpose of promoting the doctrine of Christian holiness convened. Over 10,000 came to meet God and pursue sanctification in the woods of Vineland, New Jersey. Overjoyed, the meeting’s promoters decided to form the National Camp Meeting Association for the Promotion of Holiness and hold a second encampment in 1868.

The 1868 National Camp Meeting, at Manheim, Pennsylvania, was one of the largest religious gatherings before the Moody revivals a decade later. It made celebrities of key Methodist holiness preachers and drew immediate national attention to the new movement.

Like all of the holiness camp meetings to follow, Manheim was more genteel than the frontier camp meetings of the early 1800s. The largely middle-class urban attendees had little taste for the sorts of extreme physical manifestations that had characterized those earlier gatherings. Nevertheless, as historian Melvin Dieter puts it, the atmosphere at these meetings was “packed with emotion, Methodist enthusiasm, and spiritual expectancy.”

On the opening Sunday of the Manheim meeting, over 25,000 people, including more than 300 ministers, descended on the camp area. One journalist wrote, “the weather was oppressively hot; dust was abundant, water scarce, and board most miserable.” But the attending crowd of Presbyterians, Methodists, Baptists, Dutch Reformed, Congregationalists, Quakers, and others joined in testifying to God’s goodness to them and awaited eagerly what He had in store for their week together.

The next afternoon, after a sermon by the Rev. John Thompson, another man, Dr. G. W. Woodruff, began to pray aloud, “when, all at once,” as a nationally respected minister reported, “as sudden as if a flash of lightning from the heavens had fallen upon the people, one simultaneous burst of agony and then of glory was heard in all parts of the congregation; and for nearly an hour, the scene beggared all description. … Those seated far back in the audience declared that the sensation was as if a strong wind had moved from the stand over the congregation. Several intelligent people in different parts of the congregation spoke of the same phenomenon. … Sinners stood awestricken and others fled affrighted from the congregation.” The sea of weeping, praying people was galvanized, convinced they were “face to face with God.”

Almost immediately, holiness promoters began establishing permanent camp meetings in such places as New Jersey (p. 4), Florida, Oregon, Niagara Falls, and even India. As the National Association marched across the country, it inspired numerous independent holiness associations and camp meetings, which became the movement’s backbone for the next 50 years.

So beloved were the camp meetings that many newly founded denominations (such as the Church of the Nazarene and the Pilgrim Holiness Church) began after 1900 to establish their headquarters on their sites. Denominational conferences, district and general offices, publishing houses, and even denominational Bible schools often nestled in the groves that during the summer echoed with the weeping and triumphant shouts of the saints.

—Chris Armstrong

A covenant of entire consecration

Phoebe Palmer included the covenant excerpted here in her Entire Devotion to God (1845). She counseled here readers to enter into it without delay.In the name of the Father, Son, and Holy Ghost, I do hereby consecrate body, soul, and spirit, time, talents, influence, family, and estate—all with which I stand connected, near or remote, to be for ever, and in the most unlimited sense, THE LORD’S.

My body I lay upon Thine altar, O Lord, that it may be a temple for the Holy Spirit to dwell in. From henceforth I rely upon Thy promise, that Thou wilt live and walk in me; believing, as I now surrender myself for all coming time to Thee, that Thou condescend to enter this Thy temple, and dost from this solemn moment hallow it with Thy indwelling presence.

My present and my future possessions, in family and estate, I here solemnly yield up in everlasting covenant to Thee if sent forth as Thy servant Jacob, to commence the pilgrimage of life alone, and under discouraging circumstances; yet, with him, I solemly vow, “Of all that Thou shalt give me, surely the tenth will I give unto Thee.”

Confessing that I am utterly unable to keep one of the least of Thy commandments, unless endued with power from on high, I hereby covenant to trust in Thee for the needful aid of Thy Spirit. Thou dost now behold my entire being presented to Thee a living sacrifice. Already is the offering laid upon Thine altar. Yes, my all is upon Thine altar. By the hallowing fires of burning love, let it be consumed!

O Christ, Thou dost accept the sacrifice, and through Thy meritorious life and death, the infinite efficacy of the Blood of everlasting covenant, Thou dost accept me as Thine for ever, and dost present me before the throne of the Father without spot.

And now, O Lord, I will hold fast the profession of this my faith. And as I solemnly purpose that I would sooner die than break my covenant engagements with Thee, so will I, in obedience to the command of God, hold fast the profession of my faith unwaveringly, in face of an accusing enemy and an accusing world. And this I will through Thy grace do, irrespective of my emotions.

Copyright © 2004 by the author or Christianity Today/Christian History & Biography magazine.Click here for reprint information on Christian History & Biography.