At the Battle of Manzikert, in 1071, the Seljuk Turks massacred the Byzantine Empire’s armies. The feared Turks overran Asia Minor and began to threaten even the capital of Constantinople. Meanwhile, they had also conquered Jerusalem, preventing Christian pilgrimages to the holy sites.

In 1074, Pope Gregory VII proposed leading fifty thousand volunteers to help the Christians in the East and possibly liberate the Holy Sepulchre in Jerusalem. Finally, in 1095, in response to desperate appeals from Eastern Emperor Alexius Comnenus, the new pope, Urban II, preached a stirring sermon at Clermont:

“A horrible tale has gone forth,” he said. “An accursed race utterly alienated from God … has invaded the lands of the Christians and depopulated them by the sword, plundering, and fire.” Toward the end, he made his appeal: “Tear that land from the wicked race and subject it to yourselves.”

The people were riled. They began shouting, “Deus vult! Deus vult!” (“God wills it!”) Urban II made “Deus vult” the battle cry of the Crusades.

Why the Crusaders Went

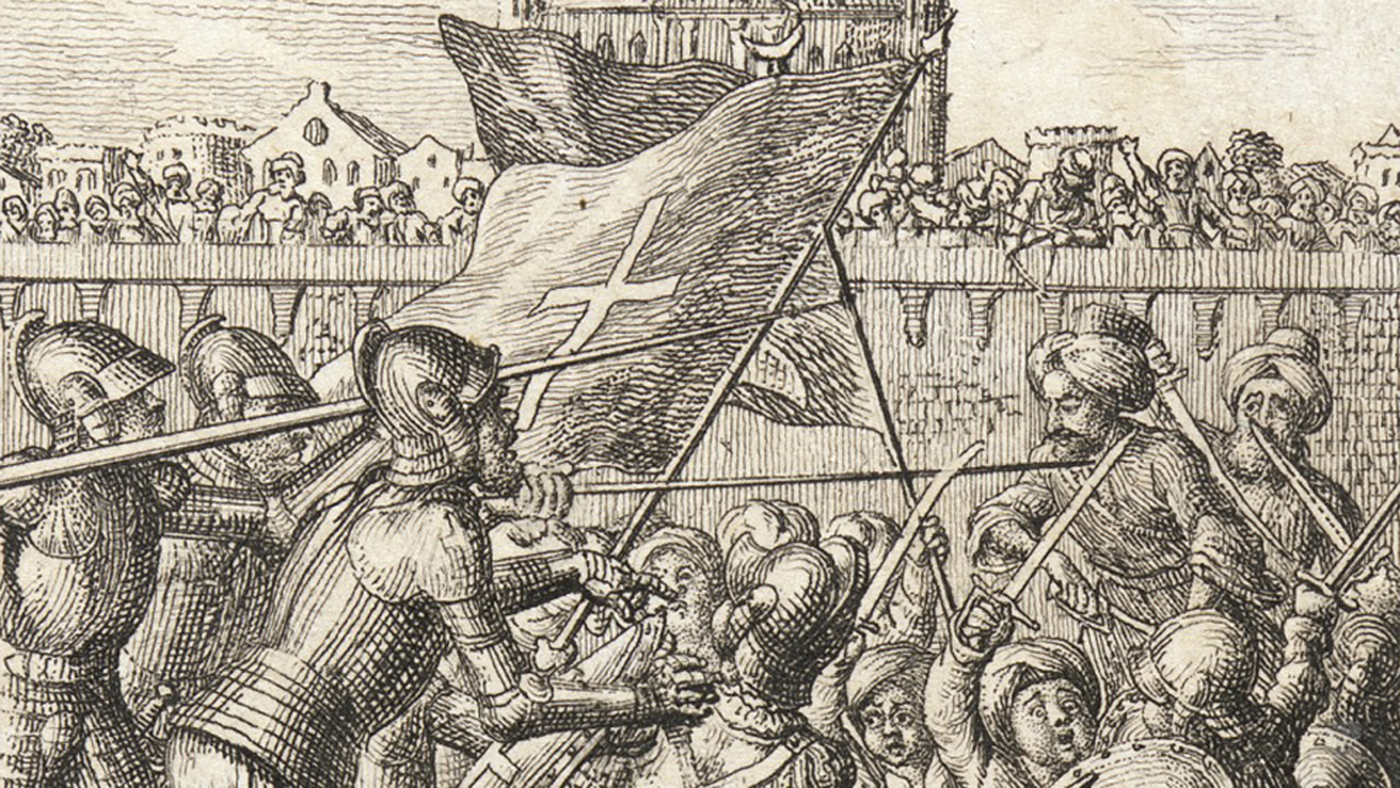

The pope’s representatives then traversed Europe, recruiting people to go to Palestine. The list of the First Crusade’s leaders read like a medieval “Who’s Who,” including the fabled Godfrey of Bouillon. Soon waves of people—probably over one hundred thousand, including about ten thousand—knights were headed for the Holy Land. Thus began over three hundred years of similar expeditions and pilgrimages, which gradually became known as crusades, because of the cross worn on the clothing of the crusaders.

Why did so many respond?

A spirit of adventure, for one thing. Pilgrimages to the Holy Land had become a feature of medieval piety, and now the pilgrimage was coupled with the prospect of fighting to recapture the pilgrimage sites, to avenge the dishonor their Lord Jesus had suffered.

The crusaders also took on an arduous journey in dismal conditions for spiritual reward. This was a holy undertaking, so participants could receive an indulgence remission of sins allowing for direct entry to heaven or reduced time in purgatory. Finally laypeople could do something that was nearly as spiritually noble as entering the monastery.

Further, many of the crusaders hoped to acquire land in the East, to plunder and grow rich.

Progress of the First Crusade

The first crusaders ventured for Constantinople, slaughtering Jews throughout Germany and occasionally skirmishing with local peoples over food and foraging rights. By late 1096, Emperor Alexius found his city of Constantinople overrun with fifty thousand unruly visitors. In exchange for the crusaders’ oaths of fealty, he provided them with supplies and sent them on. The Muslims were divided into rival factions at this time, so the crusaders advanced fairly rapidly, capturing Antioch in 1098 and Jerusalem by the following July. The crusaders followed a “take no prisoners” line; an observer at the time wrote that the soldiers “rode in blood up to their bridle reins.” Following their conquest, the crusaders set up four Latin states, including the Kingdom of Jerusalem under the rule of Godfrey of Bouillon. They built numerous structures, especially at the holy sites, and some still stand.

The First Crusade was the most successful. The Second, preached by Bernard of Clairvaux, was a stunning failure, and later ones did little to regain territory. The infamous Children’s Crusade disintegrated before it reached the Holy Land, with most of the children dying or being sold into slavery. The last Christian stronghold in Syria fell in 1291 when the Muslims captured the city of Acre. The major waves of the Crusades had ended.

Crusades’ Consequences

We find it hard to sympathize with the crusaders. Their holy wars seem like an incredibly unchristian waste of energy and time. The medieval mind, however, easily accepted the idea of fighting for—and dying for—a holy cause. Some crusaders were truly pious, while admittedly, others were just violently adventurous.

The Crusades deeply damaged Western Christians’ relations with others. When, in 1204, the knights of the Fourth Crusade sacked Constantinople, the breach between Eastern and Western Christians became wide and lasting. The major calls to crusade invariably sparked pogroms against the Jews. And the crusaders’ brutality worked only to make the Muslims more militant.

On an economic level, however, the Crusades increased trade and stepped up Europe’s economic growth. They also led to a greater interest in travel, map making, and exploration.

Modern cynics point to the Crusades as an example of Christians’ fanaticism and intolerance. In the 1990s Christians are still living down a reputation created by bands of medieval pilgrims and soldiers intent on liberating the Holy Land.

Copyright © 1990 by the author or Christianity Today/Christian History magazine. Click here for reprint information on Christian History.