In this series

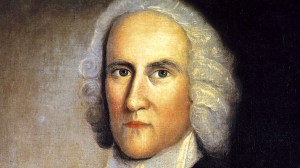

Jonathan Edwards was the only son in a family of eleven children. He and his wife Sarah had eleven children of their own.

Though John Wesley and Jonathan Edwards were born the same year (1703) and admired each other’s evangelistic work, the two men never met. Both were friends of George Whitefield and both emphasized the need for conversion and heartfelt religion. Edwards read Wesley’s Hymns and Sacred Poems and Wesley supervised the publication in England of Edwards’ Some Thoughts Concerning the Present Revival of Religion.

Edwards’ reputation as a dramatic hell-fire preacher is largely undeserved. He usually spoke quietly and with dignity, though emphatically, and his voice was unsuitable for preaching to large crowds. He never used loud volume or exaggerated gestures to make his points, for he relied on striking imagery and the logical argument of his sermons.

As part of his daily devotions, Edwards rode his horse into the woods and walked alone, meditating. He would write notes to himself on scraps of paper and pin them to his coat. On returning home, he would be met by Sarah, who would help unpin his notes.

Edwards advanced and supported the Great Awakening in New England, but viewed with suspicion the emotional excesses generated by the revival. While he encouraged repentance and heartfelt devotion to God, he was bothered somewhat by the shreiking, trances, and ecstatic deliriums that often accompanied the revivals. While the physical signs did not discredit the Awakening for Edwards, he felt some pastors placed an undue emphasis on outward signs.

Though trained to be logical and rational, Edwards insisted that true religion is primarily rooted in the affections, not in reason. He wrote the famous Treatise on Religious Affections to prove his point, and in the treatise he reveals his own deep feelings of religious devotion.

Edwards, who wrote at age thirteen an essay on spiders, always was interested in scientific matters and saw no warfare between religion and science. He read and appreciated the works of Sir Isaac Newton, and felt that good theology and good science would support and complement each other, since both were involved in the quest for truth. In writing the narrative of the New England revivals, Edwards tried to be as empirical and objectively analytical as any physicist or chemist.

After twenty-three years as pastor at Northampton, Edwards was dismissed from his post in 1750. The congregation was enraged at Edwards’ insistence that only persons who had made a profession of faith could be admitted to the Lord’s Supper. Fifty years earlier, Edwards’ grandfather Solomon Stoddard had opened the Lord’s Supper at Northampton to all who would come. The people at Northampton were determined not to have the privilege revoked, so they asked Edwards to leave.

From 1743 on, Edwards was in frequent correspondence with several Scottish ministers, all evangelical Calvinists like himself. Edwards discussed theology with his correspondents and kept them apprised on the revivals in New England. His Scottish friends helped spread Edwards’ fame in Great Britain. When Edwards was ousted from his Northampton pulpit, his Scottish friends suggested that he emigrate to Scotland and serve a Presbyterian church there.

Edwards never completed his History of the Work of Redemption, a massive theological treatise in the form of a history. To prepare himself for the task, he read every historical work he could lay his hands on. He planned to trace the workings of God from Creation to his own day. The groundwork for the treatise, a series of lectures given in 1739, was published in Scotland in 1774 and in America in 1786.

Copyright © 1985 by the author or Christianity Today/Christian History magazine. Click here for reprint information on Christian History.