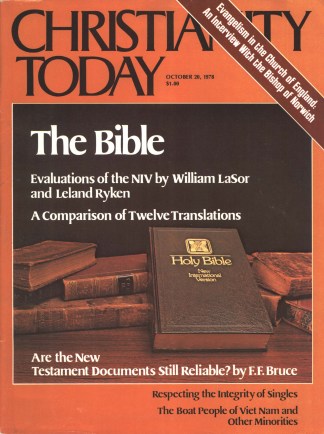

With the number of new translations of the Bible that have been published in the past thirty years, I am constantly being asked, “Which is the best version?” What I do when a new translation appears is to use portions of it for private devotional reading, portions for public reading in my classes or chapel messages, and portions for careful critical analysis in my preparation of exegetical lectures or scholarly articles. This article is based on a small sampling of the New International Version (NIV).

TYPOGRAPHY. The page proofs that were supplied to me were at once pleasing to the eye. The type is a modern type-face, clear and sufficiently bold, set in paragraphs (not in verses, like the King James Version or the New American Standard Bible) that occupy the width of the page (not in two columns, like the Revised Standard Version or the Good News Bible), with the poetic portions set in poetic form. Double-column editions are available in the NIV also. The text is divided into sections, with editorial headings set in italics as shoulder-heads before each section. Footnotes are rarely used, and then to explain the meanings of words in the text (e.g. “Lo-Ruhamah means not loved,” Hos. 1:6), or to give variant readings (e.g. “Masoretic Text; Samaritan Pentateuch, Septuagint, and Syriac: ‘He jammed the wheels of their chariots’;” Exod. 14:25), or to indicate conjectural readings or translations (e.g. “angels” in Job 38:7 has a footnote “Hebrew the sons of God”). There are no references to other passages in the side margins (as in the NASB).

READABILITY. Reading the NIV, both silently in my private use and aloud in my classes, I was pleased with the style of the work. It does not have the freshness of the GNB or the high style of the New English Bible, nor does it have the somewhat stilted style of the NASB. It reads well. On the other hand, I had the feeling that it was not markedly different from the RSV (which deliberately tries to retain the style of the KJV). In fact, when a student recently asked me, “What is the reason for the New International Version?” I was hard put for an answer, and I remarked, somewhat facetiously, “So evangelicals won’t have to use the RSV.” In my sampling, I did not find the NIV measurably superior to the RSV.

ACCURACY OF TRANSLATION. Far more important than any other critique when we are dealing with the Bible is the question, “Does it accurately translate the original text, whether Hebrew, Aramaic, or Greek?” Since we believe that the Bible is the Word of God, and since we believe that the original Scriptures were inspired so that they had the authority of God himself, we must insist that this authority be in no way diluted or diminished by faulty translation.

But before we take up the quality of the NIV translation, I would like to raise the question “What is a good translation?” There is a view that insists on word-for-word literalness. To anyone who will give this careful thought, it will become apparent that such a translation will sometimes result in nonsense, for we do not speak in words but in phrases and clauses, in sentences and paragraphs. A second view claims that a good translation must render the phrases and clauses in literal equivalents, taking into consideration figures of speech, poetic imagery, and so forth. The NASB is perhaps the best example of this kind of translation, although the KJV in the Old Testament is generally a fairly accurate translation of the Hebrew and Aramaic text. The modern trend is to insist upon a “dynamic equivalent,” the purpose of which is to create in the reader or hearer of the translation the same emotional effect that the original Scriptures would have had on their hearers and readers. The Good News and Jerusalem Bibles—and to a large extent the Living Bible—are examples of dynamic equivalents.

The New International Version is not a dynamic equivalent translation, and in this respect it is not a “modern” translation. Compare the following:

Rebuke Egypt, that wild animal in the reeds;

rebuke the nations, that herd of bulls with their calves.

until they all bow down and offer you their silver.

Scatter those people who love to make war!

Ambassadors will come from Egypt;

the Sudanese will raise their hands in prayer to God (Ps. 68:30–31, GNB).

Rebuke the beast among the reeds,

that herd of bulls among the calves of the nations.

Humbled, may it bring bars of silver.

Scatter the nations who delight in war.

Envoys will come from Egypt;

Cush will submit herself to God (Ps. 68:30–31, NIV).

The NIV is notably closer to the Hebrew text in this passage. The difficult word Mitrappēs, translated “humbled” in the NIV, is rendered “trampling under foot” in the NASB and “till every one submit himself” in the KJV. The RSV has “trample under foot.” Now, let us turn to some of the passages that present problems in any translation, and see what the NIV has done with them.

Genesis 1:1. In Hebrew, this is a dependent clause, to be translated something like, “When in the beginning God created the heavens and the earth,” with the main predication in the words “then God said, ‘Let there be light.’ ” The NIV translates it as a main clause (as do the KJV, RSV, and NASB, but not the JB, NEB, or GNB).

Genesis 6:2, 4. The problem here is not with translation, for the Hebrew text clearly reads “sons of God.” Rather, it is a matter of interpretation: Are these “sons of God” human or divine beings? In my opinion, a translation should not attempt to settle this question, but should leave it for the commentaries. The NIV translates the words literally. The GNB, on the other hand, interposes an interpretation by translating “supernatural beings,” thus unintentionally lending support to the fanciful theories of Von Däniken and others.

Exodus 20:13. The Hebrew word is murder, which is an entirely different word from the word to kill. NIV, and all recent versions that I am aware of, translate the commandment correctly, “You shall not murder.”

Psalm 2:12. The problem here is the meaning of the Hebrew word bar. When the RSV emended the text to get “kiss his feet,” evangelicals loosed a storm of protest, not realizing that the passage was a problem even to the Septuagint and Vulgate translators, as the margin in the NASB recognizes. The GNB has “bow down to him,” with several other possibilities in the margin. The NEB has “kiss the king,” with other suggestions in the margin. The NIV has “Kiss the Son,” with only a marginal note “or son.”

Psalm 23:6. The Hebrew clearly uses the verb to return: “And I shall return into the house of the Lord at length of days.” The NASB acknowledges this as “another reading” in the marginal note. The GNB gives a dynamic equivalent, “and your house will be my home as long as I live”—which, in my opinion, is not a true equivalent, for it speaks only of this life and says nothing about any hope for the life to come. The NIV goes along with the other versions by translating “and I will dwell in the house of the Lord forever.”

Psalm 45:6. The Hebrew text is to be translated either “Your throne, O God” or “Your throne is God.” The RSV translates “your divine throne,” with a marginal note giving alternate translations. The GNB reads “The kingdom that God has given you,” with marginal translations that follow the RSV and the Hebrew. The NEB reads “Your throne is like God’s throne.” The NIV has “Your throne, O God,” with no note. Some sort of note could be included, since the psalm is clearly addressed to the king (45:1), “the most excellent of men” (45:2).

Isaiah 7:14. The Hebrew clearly reads, “Behold, the young woman (is) pregnant and bearing a son.” This is not a denial of the virgin birth of Jesus, for that is clearly taught in Matthew 1:18–20 and Luke 1:31–35. I have discussed this at some length in a monograph on Isaiah 7:14, and briefly in a volume I coedited with Ward Gasque, Scripture, Tradition, and Interpretation (Eerdmans, 1978). The NEB correctly renders the Hebrew clause. The NIV translates “The virgin will be with child.”

Ezekiel 38:2. As pointed, the Hebrew word for “prince” is in construct, hence the clause must be translated “prince of Rosh, Meshech, and Tubal.” The NASB translates correctly; the RSV and NIV translate “chief prince of Meshech and Tubal.”

Daniel 7:13. The Aramaic reads “like a son of man,” which is an idiom for “human being.” The GNB renders the passage, “I saw what looked like a human being.” The NASB reads “One like a Son of Man.” The NEB’s reading, “one like a man,” is acceptable. In my opinion, the scriptural passage is capable of supporting the concept of incarnation, for the heavenly person is also human. The NIV renders “one like a son of man.”

Daniel 9:26. The Hebrew reads, “an anointed (one) will be cut off.” The RSV translates correctly. The NEB reads, “one who is anointed shall be removed,” an acceptable paraphrase. The GNB dynamically renders it, “God’s chosen leader will be killed unjustly,” which leaves for the interpreter the identification of this anointed one. But the NASB interprets rather than translates, using the term “the Messiah,” the capital M indicating a technical term, which did not come into use until the writing of the pseudepigraphic Psalms of Solomon probably within a century of the time of Christ. The NIV makes almost the same error by translating it “the Anointed One,” but offers a marginal note, “an anointed one.”

SUMMARY. This is scarcely enough material for a satisfactory evaluation. It will take months of work, at least, to isolate and study passages where there is some problem of meaning or interpretation. At this writing, I am reasonably certain that the NIV is a reliable translation. But, as is the case with all translations, every passage must be evaluated on its own merits. I think that a capable Bible student must have at least some ability to compare the translation with the original languages. At the same time, I believe that every translation throws light on some portions of God’s word, and for that reason I welcome new translations. I congratulate the team that labored long and hard to produce the NIV, and I hope that they will be willing to revise it as valid criticisms are presented.

G. Douglas Young is founder and president of the Institute of Holy Land Studies in Jerusalem. He has lived there since 1963.