The Ugandan church is full of widows and orphans.

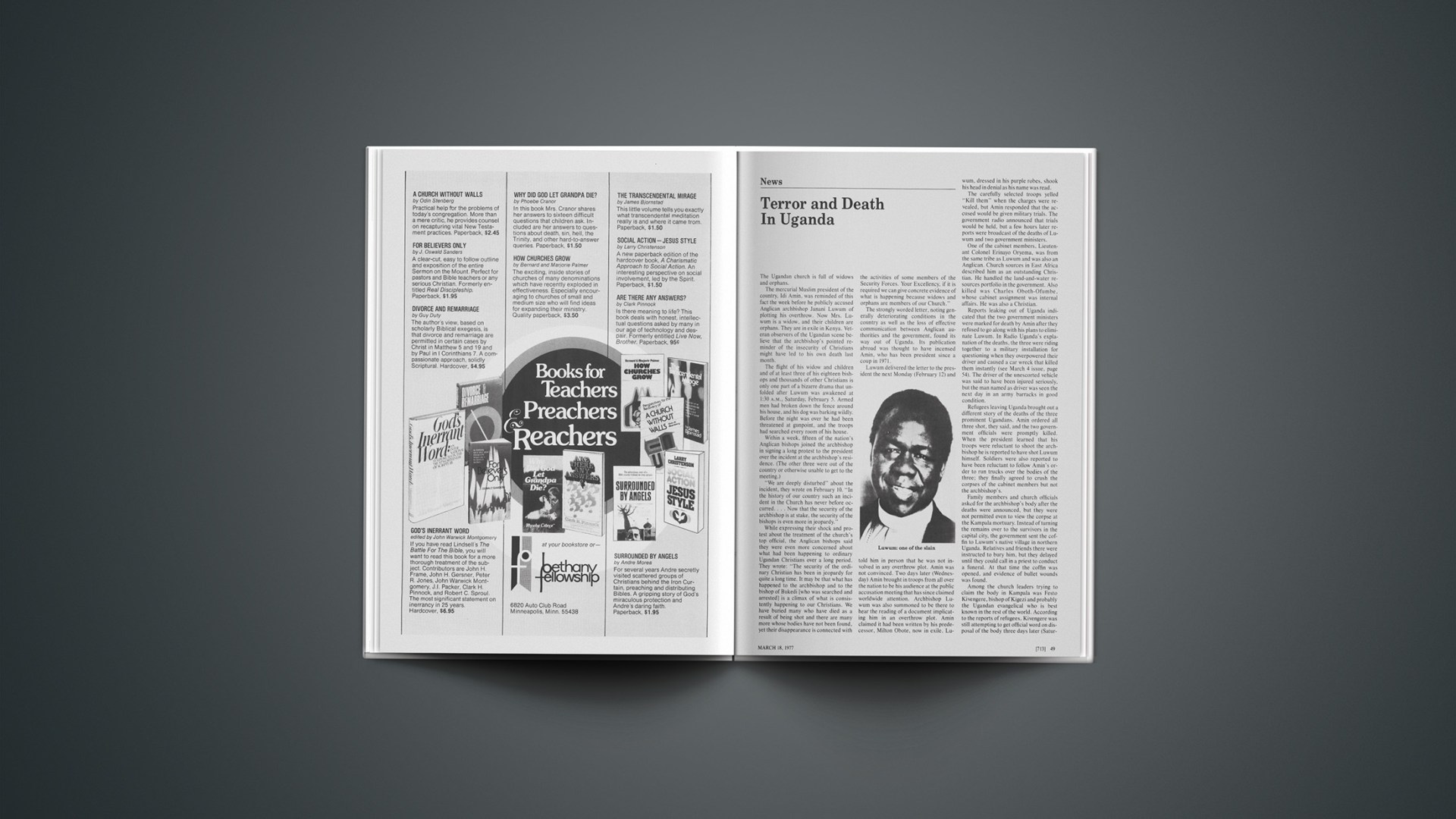

The mercurial Muslim president of the country, Idi Amin, was reminded of this fact the week before he publicly accused Anglican archbishop Janani Luwum of plotting his overthrow. Now Mrs. Luwum is a widow, and their children are orphans. They are in exile in Kenya. Veteran observers of the Ugandan scene believe that the archbishop’s pointed reminder of the insecurity of Christians might have led to his own death last month.

The flight of his widow and children and of at least three of his eighteen bishops and thousands of other Christians is only one part of a bizarre drama that unfolded after Luwum was awakened at 1:30 A.M., Saturday, February 5. Armed men had broken down the fence around his house, and his dog was barking wildly. Before the night was over he had been threatened at gunpoint, and the troops had searched every room of his house.

Within a week, fifteen of the nation’s Anglican bishops joined the archbishop in signing a long protest to the president over the incident at the archbishop’s residence. (The other three were out of the country or otherwise unable to get to the meeting.)

“We are deeply disturbed” about the incident, they wrote on February 10. “In the history of our country such an incident in the Church has never before occurred.… Now that the security of the archbishop is at stake, the security of the bishops is even more in jeopardy.”

While expressing their shock and protest about the treatment of the church’s top official, the Anglican bishops said they were even more concerned about what had been happening to ordinary Ugandan Christians over a long period. They wrote: “The security of the ordinary Christian has been in jeopardy for quite a long time. It may be that what has happened to the archbishop and to the bishop of Bukedi [who was searched and arrested] is a climax of what is consistently happening to our Christians. We have buried many who have died as a result of being shot and there are many more whose bodies have not been found, yet their disappearance is connected with the activities of some members of the Security Forces. Your Excellency, if it is required we can give concrete evidence of what is happening because widows and orphans are members of our Church.”

The strongly worded letter, noting generally deteriorating conditions in the country as well as the loss of effective communication between Anglican authorities and the government, found its way out of Uganda. Its publication abroad was thought to have incensed Amin, who has been president since a coup in 1971.

Luwum delivered the letter to the president the next Monday (February 12) and told him in person that he was not involved in any overthrow plot. Amin was not convinced. Two days later (Wednesday) Amin brought in troops from all over the nation to be his audience at the public accusation meeting that has since claimed worldwide attention. Archbishop Luwum was also summoned to be there to hear the reading of a document implicating him in an overthrow plot. Amin claimed it had been written by his predecessor, Milton Obote, now in exile. Luwum, dressed in his purple robes, shook his head in denial as his name was read.

The carefully selected troops yelled “Kill them” when the charges were revealed, but Amin responded that the accused would be given military trials. The government radio announced that trials would be held, but a few hours later reports were broadcast of the deaths of Luwum and two government ministers.

One of the cabinet members, Lieutenant Colonel Erinayo Oryema, was from the same tribe as Luwum and was also an Anglican. Church sources in East Africa described him as an outstanding Christian. He handled the land-and-water resources portfolio in the government. Also killed was Charles Oboth-Ofumbe, whose cabinet assignment was internal affairs. He was also a Christian.

Reports leaking out of Uganda indicated that the two government ministers were marked for death by Amin after they refused to go along with his plans to eliminate Luwum. In Radio Uganda’s explanation of the deaths, the three were riding together to a military installation for questioning when they overpowered their driver and caused a car wreck that killed them instantly (see March 4 issue, page 54). The driver of the unescorted vehicle was said to have been injured seriously, but the man named as driver was seen the next day in an army barracks in good condition.

Refugees leaving Uganda brought out a different story of the deaths of the three prominent Ugandans. Amin ordered all three shot, they said, and the two government officials were promptly killed. When the president learned that his troops were reluctant to shoot the archbishop he is reported to have shot Luwum himself. Soldiers were also reported to have been reluctant to follow Amin’s order to run trucks over the bodies of the three; they finally agreed to crush the corpses of the cabinet members but not the archbishop’s.

Family members and church officials asked for the archbishop’s body after the deaths were announced, but they were not permitted even to view the corpse at the Kampala mortuary. Instead of turning the remains over to the survivors in the capital city, the government sent the coffin to Luwum’s native village in northern Uganda. Relatives and friends there were instructed to bury him, but they delayed until they could call in a priest to conduct a funeral. At that time the coffin was opened, and evidence of bullet wounds was found.

Among the church leaders trying to claim the body in Kampala was Festo Kivengere, bishop of Kigezi and probably the Ugandan evangelical who is best known in the rest of the world. According to the reports of refugees, Kivengere was still attempting to get official word on disposal of the body three days later (Saturday. February 19) when he was warned by friends that Amin planned to pick him up next. At the insistence of colleagues, he then began a dramatic flight to safety in an undisclosed location outside Uganda.

Kivengere and his wife almost drove into a trap set for them by security personnel, according to the reports. They were diverted by Christians who were waiting on the highway for them outside the town where troops planned to apprehend the bishop. Another vehicle was provided for a night-time ride to the border of a neighboring country. Driving over rugged and unfamiliar terrain in darkness, they lost their way once, and once they stopped just short of driving over the side of a cliff. They traveled the last five miles out of Uganda on foot. They reached the border about 6 A.M. Sunday (February 20).

Anglican archbishop Festo Olang of Kenya had planned to go to Kampala to conduct Luwum’s funeral that Sunday, but the plans were canceled when Amin announced he had been “thanked” by the family for taking care of funeral arrangements in the archbishop’s village. He also prohibited public meetings in the cathedral.

At the time when the original service was scheduled in Uganda, a crowd estimated at 10,000 gathered in Nairobi, Kenya, for a memorial service. Bishop Leslie W. Brown of Ipswich, the last white archbishop in Uganda, represented the Church of England at the services. When he returned to London, he reported that his East African contacts spoke of the disappearance of prominent Christians from villages and towns throughout Uganda. Of accounts of the persecution of Christians he said, “I would never have believed this before.”

Luwum’s death and those of Amin’s last two Christian cabinet members apparently were just the beginning of a purge of Christians from important positions in the nation. Special targets in the sweep were members of the Langi and Acholi tribes, who were supporters of Milton Obote during his presidency and who are predominantly Christian.

When leaders around the world expressed disbelief in Amin’s explanation of the deaths, the unpredictable president went on another verbal rampage. He sent a message to the Organization of African Unity (OAU) naming the spiritual leader of the worldwide Anglican communion. Archbishop Donald Coggan of Canterbury, and the general secretary of the All Africa Conference of Churches, Burgess Carr, as conspirators in the plot to oust him. Both had flatly rejected the auto-accident explanation for Luwum’s death. Joining in the condemnation of Amin’s slaughters were such worldwide groups as Amnesty International and the International Commission of Jurists. The Vatican said it found the car-wreck story “unswallowable,” and the World Council of Churches’ executive committee condemned the Ugandan leader’s “inhuman behavior.” Billy Graham issued a statement deploring the “cold blooded murder.”

Amin was probably stung harder by the statements of leaders of governments, such as President Jimmy Carter’s declaration that his actions had “disgusted the entire civilized world.” Hearing that, Amin prohibited any Americans in the country from leaving, and he ordered them to appear before him at a Kampala meeting February 28. He also told them to bring along their chickens and goats. Although the United States closed its embassy there in 1973 and advised citizens to leave, an estimated 200 stayed, many of them missionaries. Among them were a few Southern Baptist, Seventh-day Adventist, and Africa Inland Mission personnel. There were also some seventy Roman Catholic missionaries representing several orders.

Against a backdrop of growing suspense and quiet diplomatic contacts through Arab and African governments, Amin postponed the meeting, then canceled it. The prohibition on exits was also lifted.

Lifting the pressure on Americans did not lift the pressure on Ugandan Christians, however. Informed African sources said early this month that the killings were continuing and that thousands of refugees were pouring into neighboring nations. Church leaders inside and outside Uganda called for Christians around the world to pray for divine intervention. Anglicans in many nations declared a day of prayer February 20. Commenting on the flood of messages reporting prayer on that day, one Ugandan churchman said, “We don’t want it to stop.”

The appeal for intercession comes in the year when the Ugandan church is observing its centennial. A year-long series of events had been planned by a committee headed by Archbishop Luwum. There was some speculation that Amin feared a successful national celebration would threaten his power. Some Christian leaders have claimed that 80 per cent of the population is affiliated with one of the Christian bodies, and no published estimates show less than half of the population of over 11 million as Christian.

Luwum, who was 53, was consecrated a bishop in 1970 and became archbishop in 1974. He, like many other Christian leaders in the area, was considered a product of the East Africal revival movement (see September 26, 1975, issue, page 48, and May 21, 1976, issue, page 10). An active promoter of evangelical work, he was chairman of the East Africa committee of the African Enterprise organization. He was a participant in the 1974 Lausanne congress on evangelization and in last year’s Pan African Christian Leadership Assembly. Before the 1975 World Council of Churches assembly he was one of the Anglican members of the WCC’s Central Committee.

Confrontation In Southern Africa

World attention was riveted on Uganda last month, but further south on the African continent there was also bloodshed and other violence involving churchmen.

Black nationalist guerrillas killed seven white Roman Catholic missionaries at a mission station thirty-five miles north of Salisbury, Rhodesia. Three Jesuits and four Dominican nuns were murdered at St. Paul’s mission, Musami, the Rhodesian government reported. Blamed for the raid were terrorists from the ZANU organization of Robert Mugabe, one of four black leaders participating in the Geneva talks on the future of the country. The missionaries were all from Europe.

Archbishop Patrick Chakaipa of Salisbury, Rhodesia’s first black Catholic archbishop, condemned the killings, saying that the victims were “friends and servants of the African people.” The murders were puzzling to many observers because Catholics had been among those pushing for change in Rhodesia.

Another action that puzzled churchmen at least for a few days was the raid on a Lutheran mission school near Rhodesia’s southern border with Botswana. Some 400 students were marched across the border at gunpoint, and parents made desperate efforts to bring back their children. Many of the children refused to cross the border back into Rhodesia, however, and questions arose about whether they had been forced or whether they had planned to leave in order to join the nationalist guerrillas. When Lutherans from throughout southern Africa met in Botswana last month, they thanked that nation for receiving the “refugees.” Many of the young people were put on planes for training camps in Zambia.

Pressure for a quick settlement of the Rhodesian issue continued on all sides, but most of the action seemed to be inside the country rather than at Geneva. Killings continued on both sides, with the deaths of the missionaries being only the best publicized of the war deaths. Prime Minister Ian Smith unveiled a new plan to allow black participation in areas previously closed to them, startling many of his former supporters. He still maintained a hard line against guerrillas and those supporting them, however. As one example he announced plans to deport Irish-born Roman Catholic bishop Donal R. Lamont, 65. Proceedings were started to lift Lamont’s Rhodesian citizenship as soon as a high court reduced the bishop’s ten-year sentence to four years (with three suspended). He had been convicted of violating a law that prohibits aiding guerrillas. The bishop had failed to report a nationalist request for aid at a mission.

There was also church-state confrontation in the Republic of South Africa, where both Roman Catholic and Anglican authorities announced plans to step up their opposition to government apartheid policies. As a first step, schools opened their doors to blacks and white alike. Anglican archbishop Bill Burnett of Capetown said “the society we have created for ourselves is morally indefensible.” He specifically called for an end to “banning,” the South African form of house arrest that severely limits rights to speak out and to meet with others.

In the United States, meanwhile, a black clergyman made an announcement that might have as much effect on the situation in southern Africa as any development there. Leon Sullivan of Philadelphia, who is a member of the board of General Motors, said twelve of America’s largest corporations had quietly agreed to a set of six principles “aimed to end segregation” in South Africa. The agreement provides that black employees of the multi-national corporations will be treated as the whites are.

Pressure In Plains

In early February President Jimmy Carter traveled to Georgia for the weekend and dropped by for Sunday worship at his former home church, Plains Baptist. He had apparently heard reports of a move afoot to oust Bruce Edwards as pastor. A vote indeed did come up, but only to ban cameras from services. Insiders believe Carter’s presence forestalled the anti-Edwards move.

On February 20 Carter remained in Washington and taught a Sunday-school class at First Baptist. When Edwards entered the sanctuary of the Plains church that day he noticed a number of people in the congregation who hadn’t been around for a long time, including some members who had moved out of the area. There was to be a brief business meeting to discuss how to pay for a carload of corn that had been donated to a children’s home. During the meeting, Dale Gay, stepson of men’s-class teacher Clarence Dodson, moved that Edwards be requested to resign immediately. Amid the ensuing shouting and commotion Edwards realized his opponents had enough votes to fire him (procedural votes had gone against him 88 to 62), so he announced his resignation, effective April 30 but with an immediate leave of absence.

Edwards, who came to the church in 1974, feels his stand on integration was the main reason for the opposition even though race wasn’t mentioned during the meeting. Under his leadership in November the church voted to rescind a 1965 resolution that barred blacks from membership. A move to oust him at that time failed.

One observer close to people on both sides says that more than race is involved. Many Plains members resented Edwards’s campaign work on Carter’s behalf, the source said, especially since they felt he was neglecting pastoral duties to do it. Edwards attracted criticism in defending Carter’s Playboy interview; the Democratic National Committee mailed copies of his comments to Southern Baptist churches and leaders across America. Ninety-nine Plains residents, presumably all of them white, voted for Gerald Ford in the election; they included members of Plains Baptist. The pressures on Plains and the church by tourists and the media also took a toll, says the observer. And with Carter gone, there is a lack of strong lay leadership in the church.

Deacon George Harper blamed it all on “politics and a lack of communication.” Politics, said he, “will tear up any church it gets into.” The Holy Spirit led the congregation to the decision, he added.

But deacon Hugh Carter, the President’s cousin, described the occasion as “the blackest and bloodiest day” in the history of the Plains church.

A New York Times reporter quoted a handful of people in town as saying that some church members were upset because Edwards and his wife had adopted a child of “non-Caucasian” background late last year.

The President had no comment on the resignation, and White House press secretary Jody Powell said it was time “to allow the people of that church, to the extent possible, to return to running their own affairs without involving the whole nation in their business.”

Right now the church is hurting. A lot of people aren’t speaking to each other. Fewer than forty persons were in church on the last Sunday morning of February, and some of them were tourists. The organist announced she wasn’t playing for anybody there but “only for the Lord,” and she hoped he would help her get through the service.

The Dallas Plan

Officials of the public school board in Dallas, Texas, say implementation of court-ordered desegregation was made peaceful by the community’s strong religious consciousness.

“There has been much prayer on this board of education,” says Mrs. Sarah Haskins, a Baptist who is vice-president of the Dallas Independent School District. The other board members claim religion is a major focal point in their lives, according to a Dallas Times Herald story.

President Bill Hunter, a Methodist, talks about School Superintendent Nolan Estes this way: “We know that there’s a spiritual relationship between the two of us. That relationship enables us to speak more candidly and gives us a greater range of freedom.” Estes is a deacon and chairman of the stewardship committee of the First Baptist Church of Dallas.

Faith affects policy. For example, the board recently voted six to three to approve as a source book a biology text prepared by the Creation Research Society and published by Zondervan. Even though it was listed as supplementary material and does not replace any of the state-approved texts, approval of the book has brought the board a storm of protest. Some liberal clergymen have threatened to sue to prevent the teaching of creationism in Dallas schools.

Hunter said it was a religious consciousness that held the board together when it was obliged to grapple with the desegregation order.

Dallas churches have spearheaded a community movement to “adopt” public schools in an effort to avert bitter conflicts such as have engulfed communities faced with court-ordered desegregation. Churches and synagogues have been joined by business, civic, and service organizations. Special projects have been underwritten and problems confronted. Said one volunteer: “Some church volunteers, noticing that some youngsters had no shoes, provided them the next day. Another volunteer spent two years patiently teaching a young boy to read English.”

A school district spokesman added, “The community must remain a vital part of the problem-solving mechanism. The Dallas Plan has educational programs that may become models … with its sensitivity to cultural and ethnic needs and sociological and political realities.”

Trans-Atlantic Link

Keston College, the British Center for the Study of Religion and Communism, has been seeking an American academic base in recent years, and now it has found one. Michael Bourdeaux, the center’s founder and director, announced last month that Notre Dame University had invited Keston to establish a formallink. Details are being worked out so that collaboration can begin this year.

The first step will probably be for Notre Dame to appoint a Keston-trained scholar to its staff. From Notre Dame’s Indiana campus he would make available archival material from the British center. He would also assist in personnel exchanges and conference administration.

Bourdeaux is an Anglican and works with Christians of all denominations in Eastern Europe. He said the support that Keston received from the Ford Foundation (a $30,000 grant to study Roman Catholicism in the Soviet Union) attracted the attention of Professor Donald Kommers, new director of the Center for Civil Rights at Notre Dame.

Training For Pros

Dave Rowe, key defensive lineman for the champion Oakland Raiders football team, isn’t quite up to the physical dimensions of the biblical Goliath, but he doesn’t lack much. And when he towers over you with a positive assertion, you’re unlikely to fight back.

“When I first came into football,” he said, “you could count the Christian players on your hands. Now there are more than a hundred pro athletes getting together, everyone loving everybody else. Christianity is going through pro football and other sports like wildfire. It’s amazing. I praise the Lord for this.”

The 270-pound lineman made this comment at the close of a five-day Pro Training Conference held last month near Orlando, Florida. The pros and their wives refused to be distracted by Disney World and other diversions and stayed with Bible study and deep talks on family living and Christian commitment.

Arlis Priest, a Phoenix businessman, raised $70,000 through his organization known as Pro Athletes Outreach to pay most of the travel and housing costs for this seventh annual conference. Nearly ninety football players attended, and they were joined by nine baseball players plus token representatives from bowling and golf.

Babysitting arrangements made it possible for parents to bring children; fifty came, raising the conference total 300.

Eddie Waxer, onetime Michigan State University tennis player, raised $10,000 to fly in a dozen European pro athletes and sports chaplains for the conference.

A dominant conference figure was Norm Evans, now with the Seattle Sea-hawks after playing for several seasons with the Miami Dolphins. Evans heads the player committee that helps train athletes in the art of talking about Jesus.

“Every time I come to one of these conferences, I see a new depth of maturity,” he said. “These pros from all over the United States, and now even Europe, have a new concern to see their teammates come to know Christ. They are leaving here talking about Bible studies at home and how they can help each other grow in the Lord.”

Evans and Rowe aren’t alone in this view. Mike McCoy, Notre Dame alumnus with the Green Bay Packers, senses “an awakening in sports of what people can do with their lives.”

Some of the rugged athletes were perceptibly nervous in relating their faith. Amos Martin, of the Minnesota Vikings, said: “Good thing I remembered what Norm Evans told me, ‘Take a deep breath and let Jesus do the work.’ ”

One visitor from England noted the love shown between blacks and whites at the conference. “Jesus is color blind,” said Alan Godson. “Skin color is not remotely important here. I’ve noticed black athletes have a natural flow in competition. Use it; it is a gift of God.”

The conference was related in a sense to the Sunday chapel services that are held regularly during the football and baseball seasons. Many players attending the conference were chapel leaders. All twenty-six pro football teams conduct chapel at home and away. There will be chapel services in twenty-six baseball teams also when Seattle and Toronto start big-league play this spring.

“These pros have an influence and a platform for the Lord,” said Priest. “I woke up at 4:30 in the morning of our last day in Orlando thinking about this again. We are seeing signs of great awakening. The pros left Orlando saying, ‘We’ve got to get into the Word.’ There’s more of that than ever before.”

WATSON SPOELSTRA