George Bernard Shaw wrote a great play about Joan of Arc, how she left her home and inspired the French people to battle against their English conquerors. In one scene young Prince Charles is complaining because Joan, obedient to her heavenly vision, has rebuked his softness and cowardice. With no desire to be a hero, he cries out, “I want to be just what I am. Why can’t you mind your business and let me mind mine?” The peasant girl in her fanatical zeal replies,

Minding your own business is like minding your own body; it’s the shortest way to make yourself sick. What is my business? Helping mother at home. What is thine? Petting lapdogs and sucking sugar sticks. I tell thee it is God’s business we are here to do; not our own. I have a message to thee from God; and thou must listen to it, though thy heart break with the terror of it.

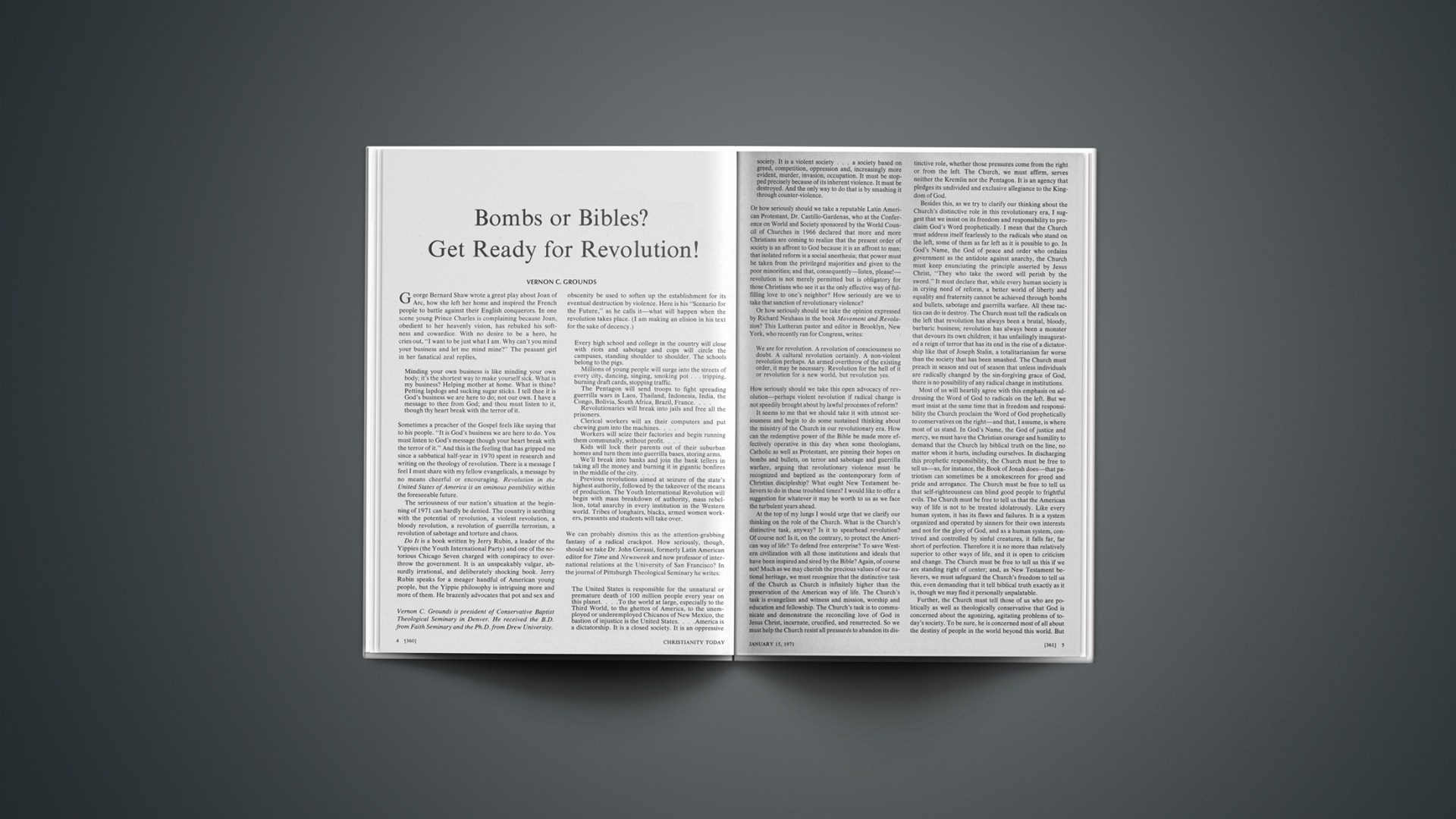

Sometimes a preacher of the Gospel feels like saying that to his people. “It is God’s business we are here to do. You must listen to God’s message though your heart break with the terror of it.” And this is the feeling that has gripped me since a sabbatical half-year in 1970 spent in research and writing on the theology of revolution. There is a message I feel I must share with my fellow evangelicals, a message by no means cheerful or encouraging. Revolution in the United States of America is an ominous possibility within the foreseeable future.

The seriousness of our nation’s situation at the beginning of 1971 can hardly be denied. The country is seething with the potential of revolution, a violent revolution, a bloody revolution, a revolution of guerrilla terrorism, a revolution of sabotage and torture and chaos.

Do It is a book written by Jerry Rubin, a leader of the Yippies (the Youth International Party) and one of the notorious Chicago Seven charged with conspiracy to overthrow the government. It is an unspeakably vulgar, absurdly irrational, and deliberately shocking book. Jerry Rubin speaks for a meager handful of American young people, but the Yippie philosophy is intriguing more and more of them. He brazenly advocates that pot and sex and obscenity be used to soften up the establishment for its eventual destruction by violence. Here is his “Scenario for the Future,” as he calls it—what will happen when the revolution takes place. (I am making an elision in his text for the sake of decency.)

Every high school and college in the country will close with riots and sabotage and cops will circle the campuses, standing shoulder to shoulder. The schools belong to the pigs.

Millions of young people will surge into the streets of every city, dancing, singing, smoking pot … tripping, burning draft cards, stopping traffic.

The Pentagon will send troops to fight spreading guerrilla wars in Laos, Thailand, Indonesia, India, the Congo, Bolivia, South Africa, Brazil, France.…

Revolutionaries will break into jails and free all the prisoners.

Clerical workers will ax their computers and put chewing gum into the machines.…

Workers will seize their factories and begin running them communally, without profit.…

Kids will lock their parents out of their suburban homes and turn them into guerrilla bases, storing arms.

We’ll break into banks and join the bank tellers in taking all the money and burning it in gigantic bonfires in the middle of the city.…

Previous revolutions aimed at seizure of the state’s highest authority, followed by the takeover of the means of production. The Youth International Revolution will begin with mass breakdown of authority, mass rebellion, total anarchy in every institution in the Western world. Tribes of longhairs, blacks, armed women workers, peasants and students will take over.

We can probably dismiss this as the attention-grabbing fantasy of a radical crackpot. How seriously, though, should we take Dr. John Gerassi, formerly Latin American editor for Time and Newsweek and now professor of international relations at the University of San Francisco? In the journal of Pittsburgh Theological Seminary he writes:

The United States is responsible for the unnatural or premature death of 100 million people every year on this planet.… To the world at large, especially to the Third World, to the ghettos of America, to the unemployed or underemployed Chicanos of New Mexico, the bastion of injustice is the United States.… America is a dictatorship. It is a closed society. It is an oppressive society. It is a violent society … a society based on greed, competition, oppression and, increasingly more evident, murder, invasion, occupation. It must be stopped precisely because of its inherent violence. It must be destroyed. And the only way to do that is by smashing it through counter-violence.

Or how seriously should we take a reputable Latin American Protestant, Dr. Castillo-Gardenas, who at the Conference on World and Society sponsored by the World Council of Churches in 1966 declared that more and more Christians are coming to realize that the present order of society is an affront to God because it is an affront to man; that isolated reform is a social anesthesia; that power must be taken from the privileged majorities and given to the poor minorities; and that, consequently—listen, please!—revolution is not merely permitted but is obligatory for those Christians who see it as the only effective way of fulfilling love to one’s neighbor? How seriously are we to take that sanction of revolutionary violence?

Or how seriously should we take the opinion expressed by Richard Neuhaus in the book Movement and Revolution? This Lutheran pastor and editor in Brooklyn, New York, who recently ran for Congress, writes:

We are for revolution. A revolution of consciousness no doubt. A cultural revolution certainly. A non-violent revolution perhaps. An armed overthrow of the existing order, it may be necessary. Revolution for the hell of it or revolution for a new world, but revolution yes.

How seriously should we take this open advocacy of revolution—perhaps violent revolution if radical change is not speedily brought about by lawful processes of reform?

It seems to me that we should take it with utmost seriousness and begin to do some sustained thinking about the ministry of the Church in our revolutionary era, How can the redemptive power of the Bible be made more effectively operative in this day when some theologians, Catholic as well as Protestant, are pinning their hopes on bombs and bullets, on terror and sabotage and guerrilla warfare, arguing that revolutionary violence must be recognized and baptized as the contemporary form of Christian discipleship? What ought New Testament believers to do in these troubled times? I would like to offer a suggestion for whatever it may be worth to us as we face the turbulent years ahead.

At the top of my lungs I would urge that we clarify our thinking on the role of the Church. What is the Church’s distinctive task, anyway? Is it to spearhead revolution? Of course not! Is it, on the contrary, to protect the American way of life? To defend free enterprise? To save Western civilization with all those institutions and ideals that have been inspired and sired by the Bible? Again, of course not! Much as we may cherish the precious values of our national heritage, we must recognize that the distinctive task of the Church as Church is infinitely higher than the preservation of the American way of life. The Church’s task is evangelism and witness and mission, worship and education and fellowship. The Church’s task is to communicate and demonstrate the reconciling love of God in Jesus Christ, incarnate, crucified, and resurrected. So we must help the Church resist all pressures to abandon its distinctive role, whether those pressures come from the right or from the left. The Church, we must affirm, serves neither the Kremlin nor the Pentagon. It is an agency that pledges its undivided and exclusive allegiance to the Kingdom of God.

Besides this, as we try to clarify our thinking about the Church’s distinctive role in this revolutionary era, I suggest that we insist on its freedom and responsibility to proclaim God’s Word prophetically. I mean that the Church must address itself fearlessly to the radicals who stand on the left, some of them as far left as it is possible to go. In God’s Name, the God of peace and order who ordains government as the antidote against anarchy, the Church must keep enunciating the principle asserted by Jesus Christ, “They who take the sword will perish by the sword.” It must declare that, while every human society is in crying need of reform, a better world of liberty and equality and fraternity cannot be achieved through bombs and bullets, sabotage and guerrilla warfare. All these tactics can do is destroy. The Church must tell the radicals on the left that revolution has always been a brutal, bloody, barbaric business; revolution has always been a monster that devours its own children; it has unfailingly inaugurated a reign of terror that has its end in the rise of a dictatorship like that of Joseph Stalin, a totalitarianism far worse than the society that has been smashed. The Church must preach in season and out of season that unless individuals are radically changed by the sin-forgiving grace of God, there is no possibility of any radical change in institutions.

Most of us will heartily agree with this emphasis on addressing the Word of God to radicals on the left. But we must insist at the same time that in freedom and responsibility the Church proclaim the Word of God prophetically to conservatives on the right—and that, I assume, is where most of us stand. In God’s Name, the God of justice and mercy, we must have the Christian courage and humility to demand that the Church lay biblical truth on the line, no matter whom it hurts, including ourselves. In discharging this prophetic responsibility, the Church must be free to tell us—as, for instance, the Book of Jonah does—that patriotism can sometimes be a smokescreen for greed and pride and arrogance. The Church must be free to tell us that self-righteousness can blind good people to frightful evils. The Church must be free to tell us that the American way of life is not to be treated idolatrously. Like every human system, it has its flaws and failures. It is a system organized and operated by sinners for their own interests and not for the glory of God, and as a human system, contrived and controlled by sinful creatures, it falls far, far short of perfection. Therefore it is no more than relatively superior to other ways of life, and it is open to criticism and change. The Church must be free to tell us this if we are standing right of center; and, as New Testament believers, we must safeguard the Church’s freedom to tell us this, even demanding that it tell biblical truth exactly as it is, though we may find it personally unpalatable.

Further, the Church must tell those of us who are politically as well as theologically conservative that God is concerned about the agonizing, agitating problems of today’s society. To be sure, he is concerned most of all about the destiny of people in the world beyond this world. But he is also concerned about this world, here and now. As Southern Baptist ethicist Foy Valentine puts it:

CHRIST-HYMN

O You!

You tiny who

Of Simeons song You

shepherds shock

You singular star-bright

You student

Shunning company

And travel

For scholars light.

Just apprentice

Of your mothers husband

True measurer

And leveler

And line

Authoritative voice

Enlisting aid

Selector

And selected

And Divine.

Creative host

Of weddings, picnics, graves

Most social

And uncelebrated

Friend

You thoughtful martyr

You thirsty man You dying God—

I hoped!

But this concludes …

Amen. Amen.

O

Heir of power

Crasher

Of closed meetings

The unsummoned

Inviting inspection—

You natural!

You Master

Of surprise.

SANDRA DUGUID

Jehovah God was portrayed by the Prophets as being concerned about such things as military alliances, the selling of debtors into slavery, the plundering of the poor by the rich, the cheating of the buyer by the seller, and the oppression of the weak by the strong. The God of the Bible, the God Christians know through personal faith in Jesus Christ, is no abstract First Cause or Prime Mover or Great Unknown out in the Great Somewhere who can be placated by a bit of discrete crying in the chapel. He is a personal God who is very deeply and very definitely concerned about military alliances, racial segregation, the unconscionable profits of the drug industry, the indefensible price fixing that honeycombs big business, and the criminal corruption that persists in organized labor. He is concerned about tax evasion, padded expense accounts, the exploitation of violence as entertainment, the toleration of senseless killings in the boxing ring, family fragmentation, and the unsolved problems of the aging. He is concerned about the unemployment which has been almost 6 per cent of our labor force in recent years … and the one hundred billion dollars a year (or about 8 per cent of its gross annual product) which the world now spends on weapons. He is concerned about the hideous inanities preached as a sorry substitute for the Christian Gospel, the infuriatingly bland and crashingly dull church programs calculated to produce an attitude of profane indifference, the immensely absurd spectacle of loving the souls of Negroes and hating their guts in America, and all the other moral flotsam and spiritual jetsam that could be orchestrated into this melancholy tune.

Dr. Valentine is right. That is the sort of thing that the Church in its prophetic ministry must be free to tell any and all of us who stand on the right. And I repeat we must protect its freedom to say these things.

I also urge that the Church must keep reminding us that God has his own program mapped out for changing the world by the personal intervention of Jesus Christ, who will return to establish the Kingdom of heaven on earth. Yet simultaneously the Church must keep reminding us that there is no biblical reason for concluding that enormous evils cannot be significantly changed before our Lord comes back. The Church, consequently, must keep reminding us as New Testament believers that, whatever our political alignment, we ought to be spiritual subversives, duplicating the redemptive radicalism of those first-century Christians who were condemned for turning the world upside-down. The Church must keep reminding us that we are God’s saboteurs working to bring about a revolution of faith and hope and love.

This, as I see it, is what we need to do in these troubled times—clarify our thinking about the distinctive role of the Church so that as members of the Church we may do our proper thing.

And who knows? If the Church by supernatural enablement more and more effectively fulfills its own distinctive task, there may come a spiritual renewal that will be as revolutionary as the Wesleyan revival in the eighteenth century. That revival spared England from the kind of bloodbath that occurred during the French Revolution. And if in divine sovereignty such a spiritual revival should be granted, we shall then appreciate the truth of a remark flung out fifty years ago by a hard-bitten leftist: “We socialists would have nothing to do if you Christians had continued the revolution begun by Jesus.” The revolution begun by Jesus, a revolution of faith and hope and love—may that revolution continue!

Vernon C. Grounds is president of Conservative Baptist Theological Seminary in Denver. He received the B.D. from Faith Seminary and the Ph.D. from Drew University.