Dear White Man:

Although we have known each other for centuries, we have not truly known each other. I, the black man, feel I know more about you because I had to. My will to survive forced me to learn about you. I was forced to learn your ways of doing things, forced to accept your concepts and values, and yet denied the right to share them. From my youth I have heard the phrase “white is right,” sometimes said in jest, but many times said with a sarcasm that can be detected only by the black man.

Do you really want to know me? I find I am skeptical—doubt that you do. Perhaps this in itself reveals some of my own psychopathology. Both you and I are suffering from the effects of many years of the poisoning of racial prejudice.

If I express my feelings and thoughts, can you understand them? Much of your conception of me has an illogical basis, and the more I tell you about myself, the more you may use, this against me. Yes, I mistrust you, because of the way you deceive yourself, and the way you have failed to look into your heart.

If I tell you that I have hostility and anger within me, how do you interpret those emotions? Do they make me a savage who will riot and burn your property? Do you ask yourself the cause of the hostility? I ask myself this question, and offer answers that at times satisfy me and at times do not. I too have become somewhat illogical, as I attempt to handle my frustrations.

No doubt some of my hostility is the outgrowth of remembering the degrading names of my youth. Could I really have accepted the reply my mother told me to give—“Sticks and stones may break my bones, but names will never hurt me”? You taught your children to hate me, and so they hurt me. When I struck out to hurt them back, I was punished by the white teacher. Can you understand the frustration of a black child caught in this situation and not knowing how to express what he feels in words? Observe his actions; they are the only way he can express his anger.

Lying somewhat deeper in this substratum of hostility are the names you made me call myself. Sometimes directly, sometimes subtly, you programmed into my early years a feeling of self-dislike, even self-hatred, and deep inferiority, so that I could not accept what God made me to be. I ask you, how does one get to know who or what he is when his society distorts what he is and tries to shape his life to prove this distortion? To the extent that a society hinders a person from developing to his God-given potential, it sins not only against that person but against God. It seems to me that our society is presently paying for the many years of wrongs done to the black man.

At times I am afraid of my anger and hostility because I don’t know what form it will or should take, and I don’t know if I will be able to hold it in check. Like Hamlet I ask myself “whether ’tis nobler in the mind to suffer the slings and arrows of outrageous fortune, or to take arms against a sea of troubles.…”

In my rational moments, I can understand that you are a product of your forefathers’ teachings, and are not entirely to blame for your feelings toward me. But if you or I should pass feelings of racial hatred to our children, we stand condemned before God.

I, the black man, am beginning to see my children develop a sense of worth, and respect for their racial heritage, and this above all gives me hope for the future.

Why have you distorted the history books and deprived my forefathers of their place in history? Why don’t you understand the need for my children to discover the roots of their racial heritage? If you can be honest with yourself as you answer these questions, then there is hope for my children and your children in the next decade.

Along with my feelings of anger and hostility, there is a strong sense of disappointment. This disappointment is felt most keenly toward those who had taught me of God’s love for all mankind. It was your missionaries who came to my native land with a message of love and mercy. When you brought me to your country against my will, you distorted God’s words to justify your evil acts. You are still doing this, and I am still forbidden to attend some of your evangelical colleges and churches, and to be your neighbor. Do you think heaven will be segregated too?

Closely connected with this feeling of disappointment is a feeling of sorrow. I am deeply sorry that you have been misled in your thinking about me these many years. We both are suffering from this. You have missed out on many of the benefits of what I could have contributed, and now the financial burden of the black man is disturbing to you. Since you have deprived me of the right to develop my mind and reach my God-given potential, you have had to help me support my family. Yet out of this perhaps will come a better value system. People are to be loved, not used. But now things are being loved, and people are being used. I feel that politicians usually do what is expedient, and that if Christians who know the love of God fail to do what is right and just, there is little hope for our country.

I have been referring to myself as the black man. But I still feel I have not been allowed to reach complete manhood. You have made me doubt my ability to compete with you intellectually, and you keep stunting this area of my life with inferior school systems. You cannot doubt my ability to compete with you physically, however—and you have used this to put a feather in your cap and money in your pockets.

It is as if my first hundred years in your country were my infancy. I was dependent upon you and I obeyed you; but I did not receive nourishment from you that would enrich me or help me to grow. I was like a foster child, not knowing my parentage and kept from knowing it. You as my foster parents used and abused me; you gave me no love, but your discipline was severe. I still remember those years. If your foster child cries out “I hate you,” perhaps you can understand that he is expressing a feeling that he has been deeply wronged.

The second hundred years were my childhood. I grew into childhood despite the methods used to keep me an infant. I started to become aware of some of these methods. I saw more of the unfairness of your treatment of me. At times I would fight back, but for the most part I continued to play the role you assigned to me. I soon learned that when I would cry out for justice, the rules became stricter, the punishment more severe. During those second hundred years I was a “boy,” and you constantly reminded me of that status.

Over the last hundred years, I progressed into the adolescent stage, and now I feel I am ready to emerge into adulthood. Don’t call me “boy” any longer, because I will no longer accept that label. Haven’t you seen the evidence of my growth? I no longer accept what you say as gospel truth, and I am not afraid to tell you. I am finding and recognizing my own identity and sense of worth. I desire to make it on my own, and I become disturbed when you tell me I’m rushing things—this process has been going on for over three centuries now. If God in his mercy allows the human race to exist, I shall achieve my full manhood in a few more years.

I am telling you these things because I do want you to know me. You have tried to observe me from afar while maintaining your myths and fantasies about me. I quote the following from a letter written by a young white person after a Christian conference where this problem was discussed:

Almost every white person I know who has been raised with prejudice and has come out of it, has done so because of a warm relationship with some Negro. This happened to me when I was seventeen, and I worked for a wonderful Negro man, who was one of the first persons I ever really loved and admired. Those who have not had this kind of experience frequently complain that they are paralyzed in relating to those with the dark skin. If they try too hard, they create resentment by gushing and realize they aren’t being very human. If they don’t try, their old prejudices come out. They are unable to be friendly in a take-it-or-leave-it way.

The patterns of a lifetime are difficult to erase. Both you and I have blind spots. We both are indwelled with an innate depravity that without the constraining power and love of Christ can cause us to destroy ourselves as well as each other. We both are prone to anger, resentment, and hostility. Yet we both respond to love and acceptance and respect, and we both have the basic drives to live, to love, and to enjoy companionship. Our experiences are different, and I may consciously or unconsciously misinterpret your intentions initially, as you may misinterpret mine. Unfortunately, those of us in the older generation must learn again to give each other a chance, something we might have been willing to do when we were children if we had been allowed to.

I, the black man, suggest that you really get to know yourself. Evaluate your life experiences and see how they may have given you your views of the black man. The only real frontier we have on earth is the frontier of human relationships. Let us hope and trust that ultimately, as we have learned to release energy from the nucleus of the atom, we shall learn to release a greater energy from the nucleus of the soul. If that happens, it will enable us to love and to live together and enjoy the blessings of God he intended us to share.

Your fellow human being and future friend,

The Black Man

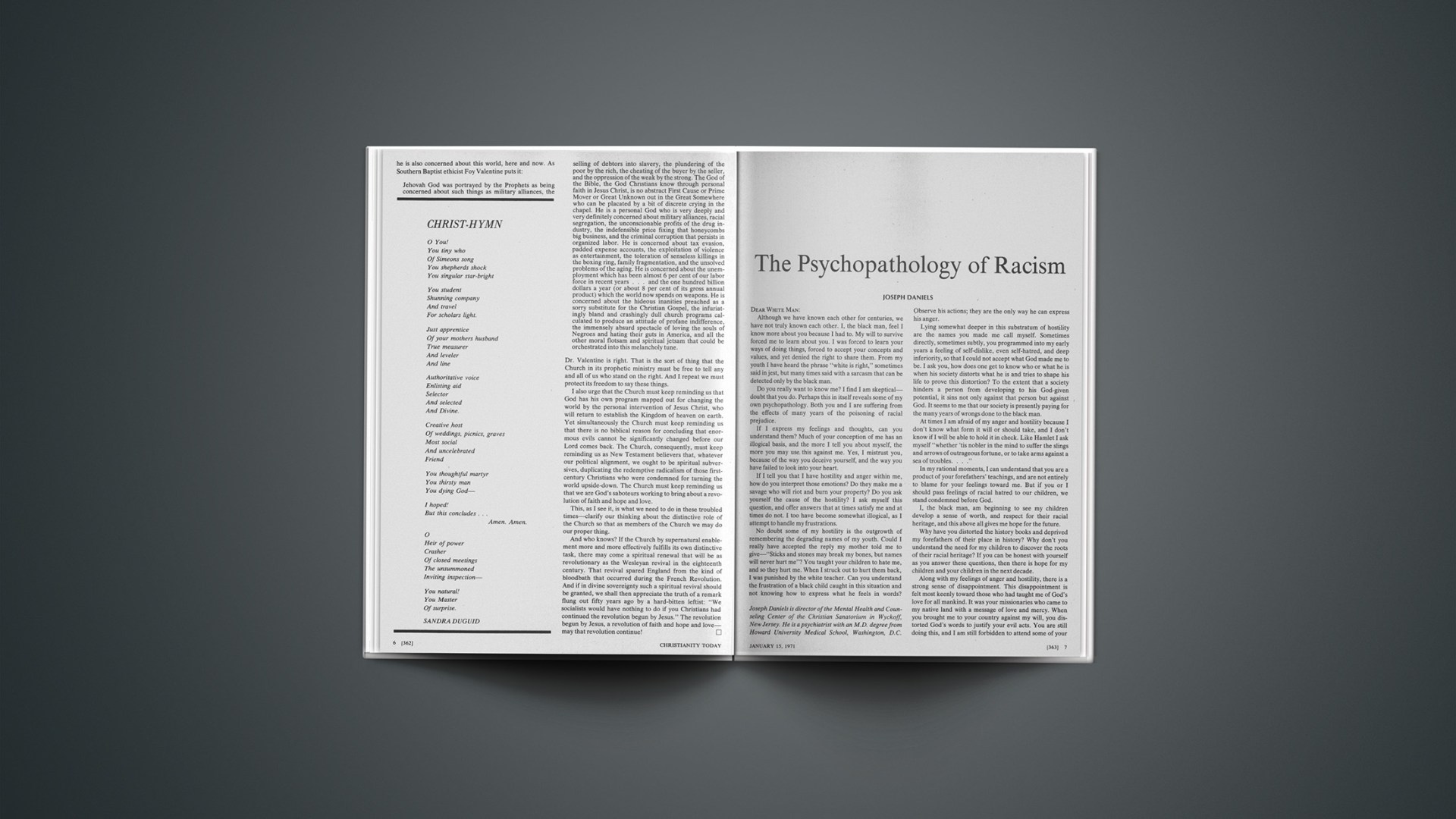

Joseph Daniels is director of the Mental Health and Counseling Center of the. Christian Sanatorium in Wyckoff, New Jersey. He is a psychiatrist with an M.D. degree from Howard University Medical School, Washington, D.C.