In the doctrine of Scripture we are dealing with the very basis of our whole theology. Even liberal theologians would generally agree with this statement. Yet there are important differences between evangelicals and liberals on this very point, for liberal theologians accept other sources as well. For instance, John Macquarrie, in his Principles of Christian Theology (1966), mentions several “formative factors in theology”: experience, revelation, Scripture, tradition, culture, and reason. By setting other factors alongside Scripture (and revelation), liberal theology severely limits the authority of Scripture. In fact, after a while the other factors—particularly experience and reason—appear to have the final word.

Evangelicals have a different starting point. They agree with the Reformers that Scripture is the only source of theology, the principium unicum, as it was called in the post-Reformation period. This is clearly stated in many Reformation and post-Reformation confessions. The Westminster Confession, for instance, says that in Scripture we find “that knowledge of God and of his will which is necessary unto salvation,” and also:

The whole counsel of God concerning all things necessary for his own glory, man’s salvation, faith and life, is either expressly set down in Scripture, or by good and necessary consequence may be deduced from Scripture: unto which nothing at any time is to be added, whether by new revelations of the Spirit, or traditions of men.

Three Views Of Scripture

To get a bird’s-eye view of the situation we can say that essentially there are three views of Scripture:

1. The old liberal view. According to this, the Bible is a purely human book. It is the record of the religious experiences of some believers in the past. Especially in Israel and later on in the Christian Church there were some men who had some deep religious experiences and a growing awareness and understanding of God. They recorded these experiences and this awareness in writing, and because of the depth of their experiences, their writings are of great value for all succeeding generations. In a sense they are even authoritative. But this authority is limited and relative. It is creative and stimulating, but it always has to be checked by our own experience and insights. In other words, it is purely subjective and never final. Only what I myself experience is final.

2. The neo-orthodox and to some extent also the neo-liberal view. Or to put it another way, the view of Barth and to some extent Bultmann. According to this view, too, the Bible is a thoroughly human book. Yet there is an important difference between this and the old liberal view, for to neo-orthodox and many neo-liberal theologians, the Bible is not only the record of subjective, human experience; primarily it is the witness to a revelation of God, namely, his revelation in Jesus Christ. As “witness” it is a purely human document. It is fallible and actually contains errors, not only in facts but also in judgments and evaluations. And yet, when God’s Spirit uses this witness and brings it “home” to us, this human and fallible witness becomes God’s Word, God’s revelation, to us.

This means that the authority of the Bible is relative and absolute at the same time. On the one hand, since it is a human witness to revelation, its authority is relative. As a human book the Bible may be freely criticized. On the other hand, when it pleases God to speak through this witness, then revelation takes place. Then God himself addresses us, and at that moment, of course, the authority is absolute.

3. The evangelical or classical view. According to this view, the Bible is the Word of God. Admittedly, it is the Word of God in the words of men; yet in these human words God himself speaks to us. One of the clearest and most persuasive expositions of the evangelical or classical view is given by B. B. Warfield in the articles collected in the volume The Inspiration and Authority of the Bible. The Bible is not “man’s report to us of what God says, but the very Word of God itself, spoken by God himself through human lips and pens.” It is “the very word of God,” says Warfield, “instinct with divine life from the ‘in the beginning’ of Genesis to the ‘Amen’ of the Apocalypse—breathed into by God and breathing out God to every devout reader.” This was the view held by our Lord himself and by his apostles. In fact, one finds it throughout the whole New Testament, when it speaks of the Old. Warfield says—and it is no exaggeration: “There are scores, hundreds of such passages; and they come bursting upon us in one solid mass. Explain them away? We should have to explain away the whole New Testament.”

We have called this the evangelical or classical view, for it was held by the whole church up till the eighteenth century, when higher criticism started and theologians tried to deny this view in order to make room for their own critical approach. It is the view held by the church fathers, by the theologians of the Middle Ages, by the Reformers and the fathers of the post-Reformation period, by all conservative and evangelical theologians of today. It is also the view held by the Church of Rome. In its Dogmatical Constitution on Divine Revelation, Vatican II declared:

The divinely revealed realities, which are contained and present in the text of sacred Scripture, have been written down under the inspiration of the Holy Spirit. For holy mother Church, relying on the faith of the apostolic age, accepts as sacred and canonical the books of the Old and New Testaments, whole and entire, with all their parts, on the grounds that, written under the inspiration of the Holy Spirit (cf. John 20:31; 2 Tim 3:16; 2 Pet 1:19–21; 3:15, 16), they have God as their author, and have been handed on as such to the Church herself.

AND THE WORD WAS MADE FLESH

Before the jingle bells the Jesus boy—

and Christ (in vain the fundamental certainty)

has not been slain upon an Xmas tree.

But incognito (like an insect drawn to flame),

as being found with human hells as man,

in being flesh—saved flesh and mistletoe and wassailing joy

(and saved the jingle bells).

ALLAN CRAIG

Unfortunately, in the case of Rome this correct view of Scripture is greatly weakened, even made powerless, because other authorities are added to the Bible, namely, oral tradition and the power of the Magisterium (the church’s teaching function) to give an authentic and infallible interpretation of Scripture. Vatican II emphatically reaffirmed these added authorities. Although both Protestant evangelicals and Roman Catholics accept the Bible as authoritative, even speak of divine authority, there is still a world of difference between them. By adding these other authorities Rome weakens the authority of the Bible to such an extent that on certain points, even decisive points, the Bible can no longer speak with authority.

The evangelical position has two great presuppositions, revelation and inspiration. It also has two important implications, authority and infallibility.

Presupposition One: Revelation

The great and basic presupposition of the evangelical doctrine of Scripture is that God has revealed himself as the Redeemer of his people. Note the wording—God has revealed himself. Revelation always is essentially self-revelation. It is not just a making known of all kinds of interesting things that we would not know about otherwise, such as the existence of a heaven and a hell, of angels and demons, and of a life hereafter. Admittedly, the Bible speaks about all these matters, but this is not the real center of the Bible and of revelation. The real heart of the biblical revelation is that God reveals himself.

He has revealed himself in two ways: (1) in his acts in history, the history of his chosen people; (2) in his words through his prophets, words addressed to his chosen people. In both cases we intentionally add the words “his chosen people.” This means a definite limitation. No, we do not deny the reality of a general self-revelation of God, going out to all people, all over the world and in every age. Many passages of Scripture speak of this general revelation (such as Psalm 19 and other psalms of nature, and Romans 1 and 2). But this general revelation is only God’s self-revelation as Creator and Ruler of the universe. There is no message of redemption in this general revelation. Moreover, the sinner refuses to acknowledge and accept this revelation. As Paul says in Romans 1, the sinner suppresses its truth in unrighteousness, and the result is idolatry: “Claiming to be wise, they became fools, and exchanged the glory of the immortal God for images resembling mortal man or birds or animals or reptiles” (vv. 22, 23).

God’s self-revelation as Redeemer, however, as it took place in history, was not general but particular. It took place in a particular segment of history, and it came to a particular people. First it came to Israel, in its history and through its prophets. But the self-revelation to Israel was not final; it was only preparatory. In the fullness of time God revealed himself in the incarnation of his Son, who was the very culmination of all previous revelation, both act- and word-revelation. He could say of himself: “I am the way, and the truth, and the life; no one comes to the Father, but by me” (John 14:6), and also: “He who has seen me has seen the Father” (14:9). He is the self-revelation of God. Commenting on the words “Hear him” (Matt. 17:5), spoken by the voice from the cloud on the Mount of Transfiguration, Calvin wrote:

In these words there is more weight and force than is commonly thought. For it is as if, leading us away from all doctrines of men, He should conduct us to his Son alone; bid us seek all teaching of salvation from Him alone; depend on Him, cleave to Him; in short (as the words themselves pronounce), hearken to his voice alone [Institutes, IV, viii, 7].

This conviction has always been the great stumbling block for adherents of other religions and also for the liberal theologians. The older liberal theology of the last century and the first quarter of this century always violently reacted against this particularism of the Christian doctrine of revelation. These theologians believed in general revelation only—insofar as they were still willing to speak of revelation at all! God reveals himself everywhere and to all people, they said, and Jesus Christ is one of the many ways to God.

It was against this purely immanentistic approach that Karl Barth reacted vehemently. He even went so far as to reject the whole idea of a general revelation through creation. The only true revelation is the revelation in Jesus Christ. At the same time, however, there was a universalistic strand in his theology. He believed that Jesus Christ bore God’s rejection for all men, believers as well as unbelievers. The only difference is that the believers know it subjectively; objectively, it is true of them all, and all we have to do is announce to the unbelievers that they have already been redeemed. Thus in Barth we find a combination of particularism (in the doctrine of revelation) and universalism (in the doctrine of redemption).

In the period since World War II there has been a strong reaction against this Christo-centrism or Christo-monism of Barth’s doctrine of revelation, in the form of neo-liberalism. Not without reason this neo-liberalism has been called a “post-Barthian” liberalism. Most neo-liberals do want to retain the idea of revelation. John Macquarrie, for instance, emphatically states that man’s faith is “made possible by the initiative of that toward which his faith is directed.” Man experiences an initiative from beyond himself, Macquarrie says. But at the same time most neo-liberals believe that revelation may not be restricted to the revelation in Jesus Christ. Undoubtedly Macquarrie speaks on behalf of many others when he says:

The stress laid by Barth and other theologians on God’s initiative in any knowledge of himself is correct and justified as a protest against the idea that God can be discovered like a fact of nature, and as an assertion that he gives the knowledge of himself; but the position of these theologians becomes distorted when they try to narrow the knowledge of God to a single self-revealing act on his part (the biblical or Christian revelation), and as against them at this point, the traditional natural theology was correct and justified in claiming a wider and indeed universal possibility for knowing God [Principles of Christian Theology, Scribner, 1966, p. 47].

It is not surprising that earlier in his book Macquarrie mentions a variety of examples of revelation side by side: the revelation granted to Moses in the desert, the one granted to the Gnostic writer who received the gospel of Poimandres, the one given to Arjuna who received a theophany of the god Krishna, and numerous others. On another page he mentions the same examples and adds the name of Jesus. The recognition of Jesus by his disciples as the Messiah is on a par with the theophanies of Poimandres and Krishna, he says. Again on another page he states that all the great religions (such as Christianity, Buddhism, Hinduism, and Islam) know “revelation, grace, the divine initiative.”

This whole view leads naturally to a new syncretism. Macquarrie himself denies this, but he can do so only by giving such a narrow definition of syncretism that his own position falls outside it. But if we accept W. Visser ’t Hooft’s definition—syncretism is “the view which holds that there is no unique revelation in history, that there are many different ways to reach the divine reality” (No Other Name)—then Macquarrie’s view is a clear example of syncretism. In fact, he himself quotes the following lines from the blind Scottish hymnwriter George Matheson:

Gather us in, thou Love that fillest all;

Gather our rival faiths within thy fold.

Rend each man’s temple-veil and bid it fall,

That we may know that thou hast been of old.

What all this means for Christology is obvious. Jesus Christ is only an “instance” of revelation. Macquarrie is willing to say that “for the Christian faith” Jesus Christ is “the decisive or paradigmatic revelation of God,” but the addition “for the Christian faith” means a thorough relativizing of Christ. Finally, he couples it all with a theory of universalism. The end is “a commonwealth of free responsible beings united in love.” The doctrine of an eternal hell he calls “barbarous”—“even earthly penologists are more enlightened nowadays.” Naturally this theology means the end of all mission work, though Macquarrie tries to retain it somehow. He still speaks of mission, but it is no longer a matter of gaining converts, of winning the world for Christ; mission is now “self-giving that lets be.” “The time has come for Christianity and the other great world religions to think in terms of sharing a mission to the loveless and unloved masses of humanity, rather than in sending missions to convert each other.” This he calls a “global ecumenism.”

We have focused on the views of Macquarrie, not because they are particularly original (he is deeply influenced by Bultmann and Tillich; one could call his theology a version of Tillich’s), but because they are symptomatic of much modern theology. In these views we see the consequences of rejecting the particularistic character of God’s self-revelation as Redeemer. As soon as one abandons the biblical teaching that Jesus Christ is the revelation of God, that all redemptive revelation has its center in him, then the whole Christian message changes. Christianity becomes one of the many ways to God. Jesus Christ himself becomes one of the many revelations of God.

In the Bible we find quite a different message. The Bible does tell us there is a general revelation of God in nature and history, and because of this general revelation there are certain elements of truth in other religions. But the revelation in Jesus Christ is not just a particular instance of this general revelation; it is an altogether new revelation—God’s self-revelation, not only as Creator but also as Redeemer. As redemptive revelation, it is unique. We see that very clearly in Paul’s sermon on the Areopagus. Paul preaches Jesus not as the continuation of the heathen religion but as the new revelation. “But,” Paul says—note the contrast!—“now [a new situation has arisen, compared with the “times of ignorance”] God commands all men everywhere to repent, because he has fixed a day on which he will judge the world in righteousness by a man whom he has appointed, and of this he has given assurance to all men by raising him from the dead” (Acts 17:30, 31).

There is only one true and redemptive revelation: God’s self-revelation in his incarnate Son, Jesus Christ. And this revelation has been recorded in Scripture, in both the Old and the New Testament. Both speak of Jesus Christ, the Old Testament by pointing forward to him, the New Testament by pointing backward to him. Both speak of him in such a way that this Bible is the Word of God, that is, God’s self-revelation to us.

Presupposition Two: Inspiration

But how is this possible? How can a book written by men (there is no doubt about this) be the Word of God? Here we come to the second great presupposition of the evangelical doctrine of Scripture. Evangelicals believe that the Bible writers were inspired by the Holy Spirit and that therefore the book itself can be called the inspired Word of God.

For the liberals, both the older and the neo-liberals, there is hardly any place left for inspiration. They are willing to allow for some kind of illumination, but this illumination of the Bible writers is of the same nature as that which all believers receive. It may be a little “higher” or “stronger,” but this is only a difference of degree. Of the Bible itself one can only say that it is inspired because it inspires. In other words, inspiration is little more than a subjective concept.

Neo-orthodox theologians generally do accept the inspiration of Scripture. They believe that the Bible writers were impelled, surrounded, and controlled by the Holy Spirit. But this action of the Holy Spirit does not mean that therefore their writings are the Word of God. The writings are still no more than “witnesses” to the Word of God. They become the Word of God only when the Holy Spirit works on the readers and enables them to receive this witness and to hear the voice of God in it. This activity of the Spirit upon the readers and listeners of today is also part of inspiration. In fact, only when this second phase is added is the act of inspiration completed; only then can one speak of the Word of God. In other words, while the liberal subjectivizes and relativizes inspiration, the neo-orthodox actualizes it. It is something that happens again and again. But in both cases the result is that the Bible itself is no more than an ordinary human book. For the liberal, it is a book of religious experiences. For the neo-orthodox, it is a witness to God’s revelation in Christ. But in both cases it must be distinguished from the Word of God itself. It is a human document and as such is limited and fallible.

The evangelical position is quite different. Evangelicals believe that the Holy Spirit so worked upon the Bible writers that what they wrote is not just a human word but indeed and fully the Word of God for us, their readers. There is no need to go into details. Everyone who reads the New Testament carefully knows that it always quotes the Old Testament as the Word of God. This was the attitude of both the Lord Jesus Christ himself and all his apostles.

In addition, there are some clear statements on the matter. Second Peter 1:21 is very important: “No prophecy ever came by the impulse of man, but men moved by the Holy Spirit spoke from God.” In the last part of this verse three important statements are made. (1) Men spoke. They were real men, not just passive instruments, as some early church fathers and some post-Reformation theologians who defended a mechanical conception of inspiration said; they were real, living men who were personally involved in the whole process of speaking and/or writing. (2) These men were moved by the Holy Spirit. Literally the text says: they were borne along by the Spirit as a ship is borne along by the wind. (3) The result of this “being moved” was that they spoke from God (apo theou). Their word was God’s word. It was nothing less than revelation to those who listened to them. In this verse Peter speaks of the Old Testament prophets in their prophetic activity, but it is not limited to them. According to Paul in Second Timothy 3:16, it is true of the whole Old Testament—“All Scripture is inspired of God [pasa graphe theopneustos].” No part is exempt. The whole of Scripture and every part of it is inspired, that is, written under the guidance of the Spirit.

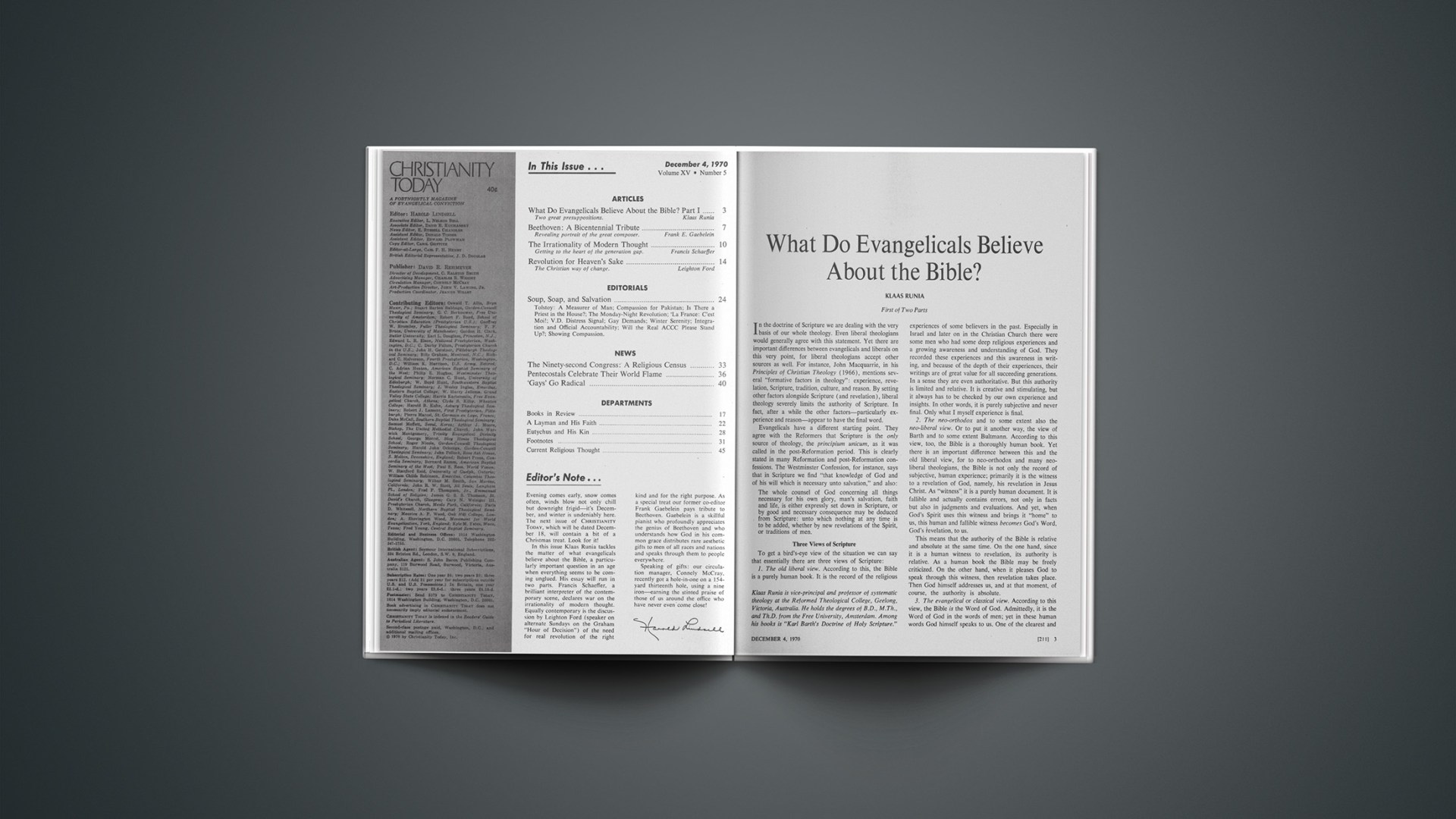

Klaus Runia is vice-principal and professor of systematic theology at the Reformed Theological College, Geelong, Victoria, Australia. He holds the degrees of B. D., M.Th., and Th.D. from the Free University, Amsterdam. Among his books is “Karl Barth’s Doctrine of Holy Scripture.”