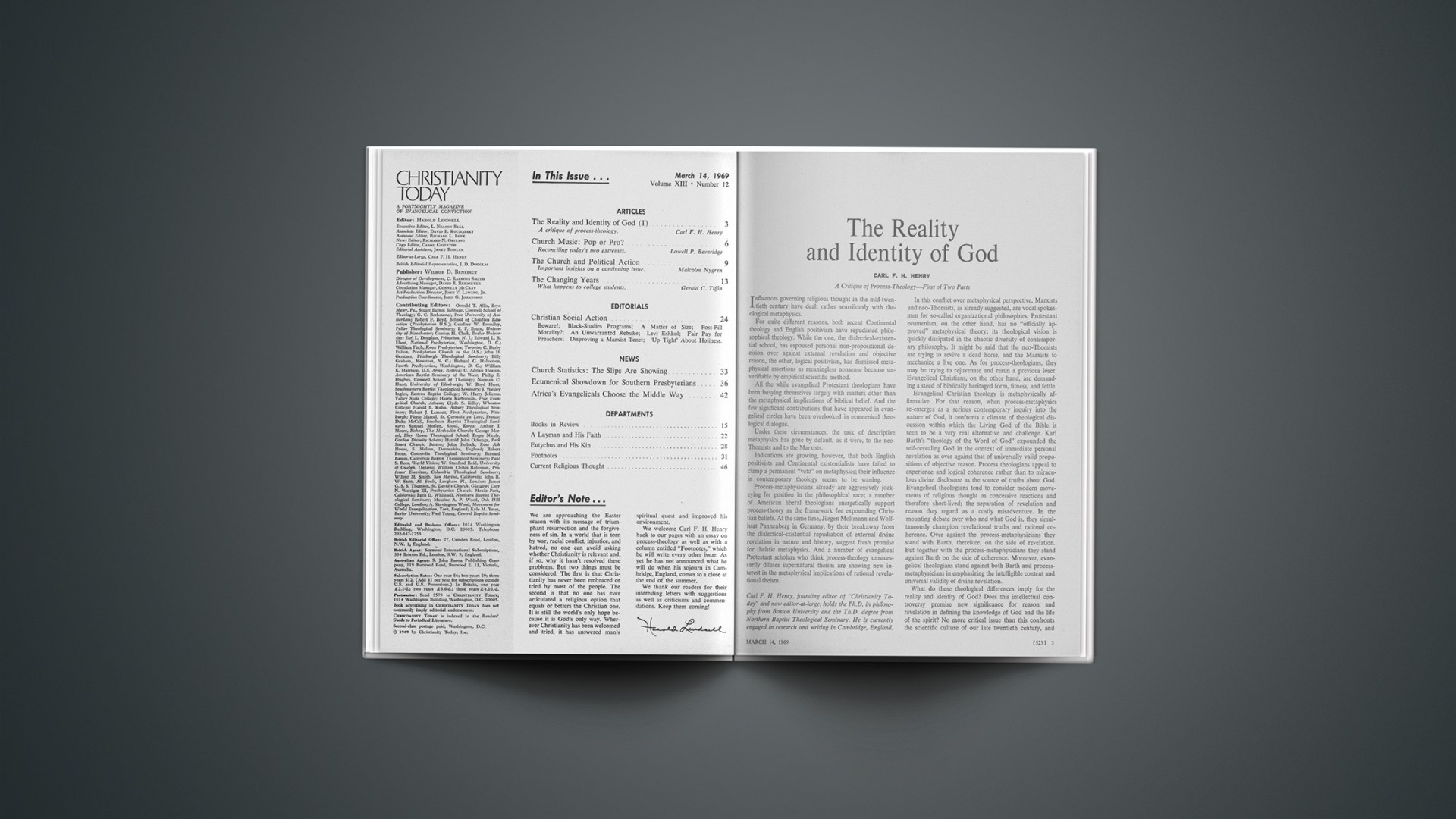

A Critique of Process-Theology—First of Two Parts

Influences governing religious thought in the mid-twentieth century have dealt rather scurrilously with theological metaphysics.

For quite different reasons, both recent Continental theology and English positivism have repudiated philosophical theology. While the one, the dialectical-existential school, has espoused personal non-propositional decision over against external revelation and objective reason, the other, logical positivism, has dismissed metaphysical assertions as meaningless nonsense because unverifiable by empirical scientific method.

All the while evangelical Protestant theologians have been busying themselves largely with matters other than the metaphysical implications of biblical belief. And the few significant contributions that have appeared in evangelical circles have been overlooked in ecumenical theological dialogue.

Under these circumstances, the task of descriptive metaphysics has gone by default, as it were, to the neo-Thomists and to the Marxists.

Indications are growing, however, that both English positivists and Continental existentialists have failed to clamp a permanent “veto” on metaphysics; their influence in contemporary theology seems to be waning.

Process-metaphysicians already are aggressively jockeying for position in the philosophical race; a number of American liberal theologians energetically support process-theory as the framework for expounding Christian beliefs. At the same time, Jürgen Moltmann and Wolf-hart Pannenberg in Germany, by their breakaway from the dialectical-existential repudiation of external divine revelation in nature and history, suggest fresh promise for theistic metaphysics. And a number of evangelical Protestant scholars who think process-theology unnecessarily dilutes supernatural theism are showing new interest in the metaphysical implications of rational revelational theism.

In this conflict over metaphysical perspective, Marxists and neo-Thomists, as already suggested, are vocal spokesmen for so-called organizational philosophies. Protestant ecumenism, on the other hand, has no “officially approved” metaphysical theory; its theological vision is quickly dissipated in the chaotic diversity of contemporary philosophy. It might be said that the neo-Thomists are trying to revive a dead horse, and the Marxists to mechanize a live one. As for process-theologians, they may be trying to rejuvenate and rerun a previous loser. Evangelical Christians, on the other hand, are demanding a steed of biblically heritaged form, fitness, and fettle.

Evangelical Christian theology is metaphysically affirmative. For that reason, when process-metaphysics re-emerges as a serious contemporary inquiry into the nature of God, it confronts a climate of theological discussion within which the Living God of the Bible is seen to be a very real alternative and challenge. Karl Barth’s “theology of the Word of God” expounded the self-revealing God in the context of immediate personal revelation as over against that of universally valid propositions of objective reason. Process theologians appeal to experience and logical coherence rather than to miraculous divine disclosure as the source of truths about God. Evangelical theologians tend to consider modern movements of religious thought as concessive reactions and therefore short-lived; the separation of revelation and reason they regard as a costly misadventure. In the mounting debate over who and what God is, they simultaneously champion revelational truths and rational coherence. Over against the process-metaphysicians they stand with Barth, therefore, on the side of revelation. But together with the process-metaphysicians they stand against Barth on the side of coherence. Moreover, evangelical theologians stand against both Barth and process-metaphysicians in emphasizing the intelligible content and universal validity of divine revelation.

What do these theological differences imply for the reality and identity of God? Does this intellectual controversy promise new significance for reason and revelation in defining the knowledge of God and the life of the spirit? No more critical issue than this confronts the scientific culture of our late twentieth century, and no responsible theologian will sidestep engagement in it.

Process-metaphysics is not a new nor even a modern theory, though its recent form has distinctively fresh features. In its post-Christian format, it tries to correlate the evolutionary view of a growing universe with that of a religious reality which, though directly and necessarily involved in time and space, somehow transcends and guides the process of which it is a part. Unlike traditional Christian theism, process-metaphysics does not totally differentiate God from the universe, but neither does it, like pantheism, identify God with the whole of reality. On the basis of evolutionary theory, process-philosophy assimilates God to the universe more immanently than Christian orthodoxy allows; in fact, it repudiates God’s absolute transcendence by making creation inevitable if not necessary to his being. Process philosophers emphasize the temporal flow of all reality; time, as they see it, is an ingriedient of Being itself.

Even in its post-Christian statement, process-metaphysics has taken a number of forms. All of them depart from orthodox Christian theology by importing part of the creative process into the inner reality of God; they differ, however, in how they distinguish the universe, or aspects of it, from divine being.

Late in the nineteenth century, process-philosophy found a prophet in the French philosopher Henri Bergson (Creative Evolution, 1911), and early in this century, in England, it gained quasi-naturalistic statement by Samuel Alexander (Space, Time and Deity, 1927) and quasipantheistic statement by C. Lloyd Morgan (Emergent Evolution, 1926). (For an evangelical critique see C. F. H. Henry, Remaking the Modern Mind, Eerdmans, 1948.) Both Bergson and Alexander had influenced Alfred North Whitehead before he left Cambridge for Harvard. Whitehead’s subsequent Process and Reality (1929) attracted such attention that he is now widely credited as the seminal mind and formative influence in later definitive statements of process-metaphysics. The so-called Lotze-Bowne tradition of “personalism,” which A. S. Knudson and E. S. Brightman influentially expounded in America, was somewhat competitive; its premise was that while the physical world is a part of God (is God’s externalized thought), human selves are divine creations other than God. (The influence of this tradition on an American evangelical theologian is sketched in C. F. H. Henry, Strong’s Theology and Personal Idealism, Van Kampen, 1951.) In Whitehead’s view, however, the structure of all being is the eternal order in the mind of God, and all reality (God included) manifests a real history of actual events.

Whatever attention process-metaphysicians commanded in England and the United States was largely eclipsed in the mid-thirties by the impact of Barthian theology, which stressed divine transcendence and the impropriety of depicting Christianity in terms of evolutionary immanence, and by the rise of logical positivism, which was more interested in physics than in biological process. But even through this period American interest in the process-concept of deity was maintained somewhat through the exposition and development of Whitehead’s thought by Charles Hartshorne (Man’s Vision of God, 1941; The Divine Relativity, 1948).

Through the breakdown of the logical positivist indictment of metaphysics, and the faltering of dialectical-existential theory, supporters of process-metaphysics gained a propitious opportunity to reassert their view, just at a time when interest in metaphysics was beginning to revive. Since then, the significant development in process-metaphysics has been its growing support by a number of American Protestant theologians as the preferred vehicle for expounding Christian theology. Among them are Bernard Meland, The Realities of Faith (1962); John Cobb, Jr., Towards a Christian Natural Theology (1965); Schubert M. Ogden, The Reality of God (1967); W. Norman Pittenger, Process Thought and Christian Faith (1968); and Daniel Day Williams, The Spirit and the Forms of Love (1968). In England process thought has waned since the twenties and thirties, when at Cambridge J. F. Bethune-Baker, Canon C. E. Raven, and H. C. Bouquet showed some interest, though Pittenger has recently retired to King’s College, his alma mater, and is promoting process-theory. Also at Cambridge, a Trinity College research scholar, Peter Hamilton, wrote a volume entitled The Living God and the Modern World (1967); in it he proposes a Christian theology based on Whitehead’s thought. A number of Roman Catholic writers—among them Teilhard de Chardin, Peter Schoonenberg, and Leslie Dewart—express a similar trend. It is necessary, therefore, to recognize process-theology for what it is: a movement trying aggressively to articulate metaphysics on a presumably Christian basis in order to overcome the recent dearth of metaphysical theology.

What is its theological methodology? What is its view of God and the world? Is process-metaphysics authentically biblical?

Daniel Day Williams has given the fullest schematic statement by a process-theologian of the theory’s implications for the Christian view of God. His basic premise in The Spirit and the Forms of Love (Harper & Row, 1968) is that the structures of human existence reflect the being of God or Divine Love. God is mirrored, he contends, in the categorical structures of human love, including the conditions of historical existence, limitation of freedom by another’s freedom, suffering, and risk.

Foundational to Williams’s experiential appeal is a skeptical view of the reliability of the Gospels and a relativistic view of truth.

Jesus’ words are said to be so qualified and reinterpreted that we cannot be sure what he said and did (The Spirit and the Forms of Love, p. 157). Quite apart from the miracles, however, Jesus is the Incarnate Logos, “the Truth acted out in love.” Creative Divine Love is the metaphysical ground of everything else.

But both love and intellectuality have a history (ibid., p. 294). Williams concurs with the dogma of scientific evolutionary philosophy that “the structures which reason abstracts are set in the concreteness of process,” and so considers all rational formulations to be tentative (p. 286). His doctrine of Divine Love as creative becoming therefore relativizes both revelation and reason. Possibly, despite Williams’s intentions, even love may not escape this fate. For it is difficult to see how Williams can exempt his own view from the premise he invokes to discredit all earlier views: “In a creative history where God opens up new possibilities of understanding it is an error to confine the meaning of reason to the historical forms of certain cultural presuppositions and values” (p. 297). What’s more, if this assertion is an epistemological absolute, it is self-refuting; if it is not, it still breaks down. In either event, the premise dooms all truth—the truth of Christianity included—to cultural relativity, and ultimately overtakes and judges Williams’s view as well. Williams, in fact, cautiously contends, not that his view is superior or impervious, but that other views are outmoded (p. 294). Perhaps, we might add, it would be safer merely to insist that one’s own view is not yet passe. For all pretensions to enduring truths are twice relativized in a creative process in which God is assertedly changing and growing, and in which man’s knowledge is assertedly culture-bound.

Instead of appealing to intelligible divine self-revelation, which is the strength of traditional Christian theism, Williams’s theological method relies on the analogy of being, and in a highly selective way. The central realities of our self-understanding, the categorical conditions of human life—namely, time, freedom, self-limitation by another’s freedom, historical existence, action and causality, suffering, risk—have metaphysical consequences, says Williams, for the analysis of God’s love, and hence of his very being. The analogy, he claims, explodes the doctrine of God’s absolute simplicity, unchangeableness, impassability, and preferential election-love, and requires instead the view that God is neither absolutely transcendent nor completely perfect, but is creatively relational and temporal (p. 123). The necessary result is said to be a reconception of the being of God that involves the divine nature both in time and in becoming. The relation of love to suffering in human experience is said to imply similar consequences for God in his historical involvement (p. 91). In reconceiving the Creator-Redeemer of the Bible as creative being, Williams uses the human analogy of love’s “dealing with broken relationships and the consequent suffering” to restate the incarnation and atonement of Christ (pp. 40 f.) in a way that accommodates “the fully social relationship of God and man” (p. 55).

The difficulty of metaphysical theology built on an appeal to analogy, Williams concedes, “is to carry through the analogy of being with full justice both to the structures of experience and to the transmutation of structures as they apply to the being of God” (p. 124). And in extrapolating agape from human experience, Williams faces a greater problem than he seems to recognize. For the christological foundation of ethics turns on whether agape is divinely derived or present in the experience of sinful man. Williams wavers: on the one hand he refuses to identify the form of any human life with agape (p. 204), but on the other he thinks agape may be present even in humanitarian concern (pp. 260 ff.).

What Williams actually does is to invoke analogy inconsistently without disclosing that this selectivity rests upon convictions about God previously held and otherwise derived. Indeed, even the premise that “love is the key to being” reflects this selective approach, for human experience entails far more than love. And human love falls at times into disorder and perversity, features that Greek mythology readily attributed even to the gods.

Williams concedes that there are undeniable differences between the divine and human: “There is indeed a dimension in the love of God which differs from human love” (p. 139). It is hard to see, however, just how Williams derives such information from an analysis of human existence. He says: “God as a reality which is necessary to all being cannot sustain exactly the same relationship to time, space and change, which the creatures exhibit.… God does not come to be or pass away” (p. 124). This apparent acknowledgment of God’s qualitatively different being, whose relation to the universe does not involve God’s own becoming, nor experiences that constitute his essential reality in a new way—such acknowledgment in principle demolishes the argument that temporality, mutability, and suffering must be posited of God analogically of man’s experience, for what structures man’s relationships need not then structure God’s. Indeed, Williams is impelled to concede that “there is that in God which does not suffer at all,” for his relationship to the world’s suffering does not involve finite limitations (p. 128), and he also protests any attempt to “fit Jesus’ experience to our limited understanding” because “we cannot delimit another’s experience by our own” (p. 162).

But these commendable observations—which would require a higher principle than the analogy of being to define the nature of God—are set aside to give metaphysical speculation the right of way. We are told that analysis of the structures of human experience, as illuminating the ultimate world, constitutes “the sole justification of metaphysical thought” (p. 129), and that “whatever is present in the inescapable structures of human experience” must be present in “being-itself.” “It is the essence of God to move the world toward new possibilities, and his being is ‘complete’ only as an infinite series of creative acts, each of which enriches, modifies, and shapes the whole society of being” (p. 139). God’s love for others is said to involve suffering that alters his experience (p. 127).

To the degree that Williams exempts the nature of God from structures found in finite, changing experience, he holds a view of God that is not derived from analogy predicated on human relationships but is in secret debt, rather, to revelational theism, at least insofar as his attributions agree with the Living God of the Bible. To the extent that he limits the nature of God to human structures, to that extent he objectionably compromises the God of Judeo-Christian revelation. How, on the basis of analogical argument, can Williams speak of “that in God which does not suffer at all” if, as he contends, love inherently involves suffering—unless, contrary to what he contends elsewhere, God’s being is not wholly identical with love?

According to the Scriptures, fallen man loves neither God nor neighbor as he ought. The gulf between divine, and human love might seem therefore to require the non-analogy of being, without thereby necessarily denying to man the fractured remnants of the divine image. May it not be the height of human presumption, rather than the mark of a meritorious theology, to project divine love from within an experience of human love that needs always to be not only fulfilled but also redeemed? The fact and nature of God’s love, if deducible at all, are deducible only from some higher principle than human analogy, indeed, from intelligible divine self-revelation alone.

Why do process-theologians object to the evangelical view of God? Basically, they read into the historic Christian view that God is supernatural, absolute, timeless and immutable the outlines of the immovable static Being of Greek philosophy; in this interpretation, time and man are sacrificed to God’s eternity. They propose, instead, a God of temporality and becoming.

This tendency of process-theology to identify the God of classical Christian theism with the static Being of Greek philosophy actually overlooks several important considerations: (1) Classic Greek philosophy itself wrestled with the problem of eternity and time and tried, however unsuccessfully, to save significance for the temporal; (2) ever since its New Testament beginnings, evangelical Christianity has affirmed a supernatural Creator who is active and personally involved in history; by emphasizing God’s election-love and the incarnation, atonement, and resurrection of the Logos, it espoused a divine relationship to the universe irreconcilable with Greek notions of a “self-contained static God”; (3) the Protestant Reformers repudiated the medieval scholastic attempt to expound the God of the Bible in Greek philosophical motifs; (4) neither the Church Fathers, the Protestant Reformers, nor recent evangelical theologians have found in the biblical view of God’s relation to the world any need to repudiate the absoluteness, non-temporality, and immutability of God.

In view of these observations, it appears that process-theology’s proposal to redefine the nature of the Divine as creative becoming does not rest on evangelical and biblical motivations. It issues, rather, from attempts to fuse modern evolutionary theory with arbitrarily selected elements of the scriptural heritage. And therefore it substitutes a modern speculative abstraction for the God of the Bible.