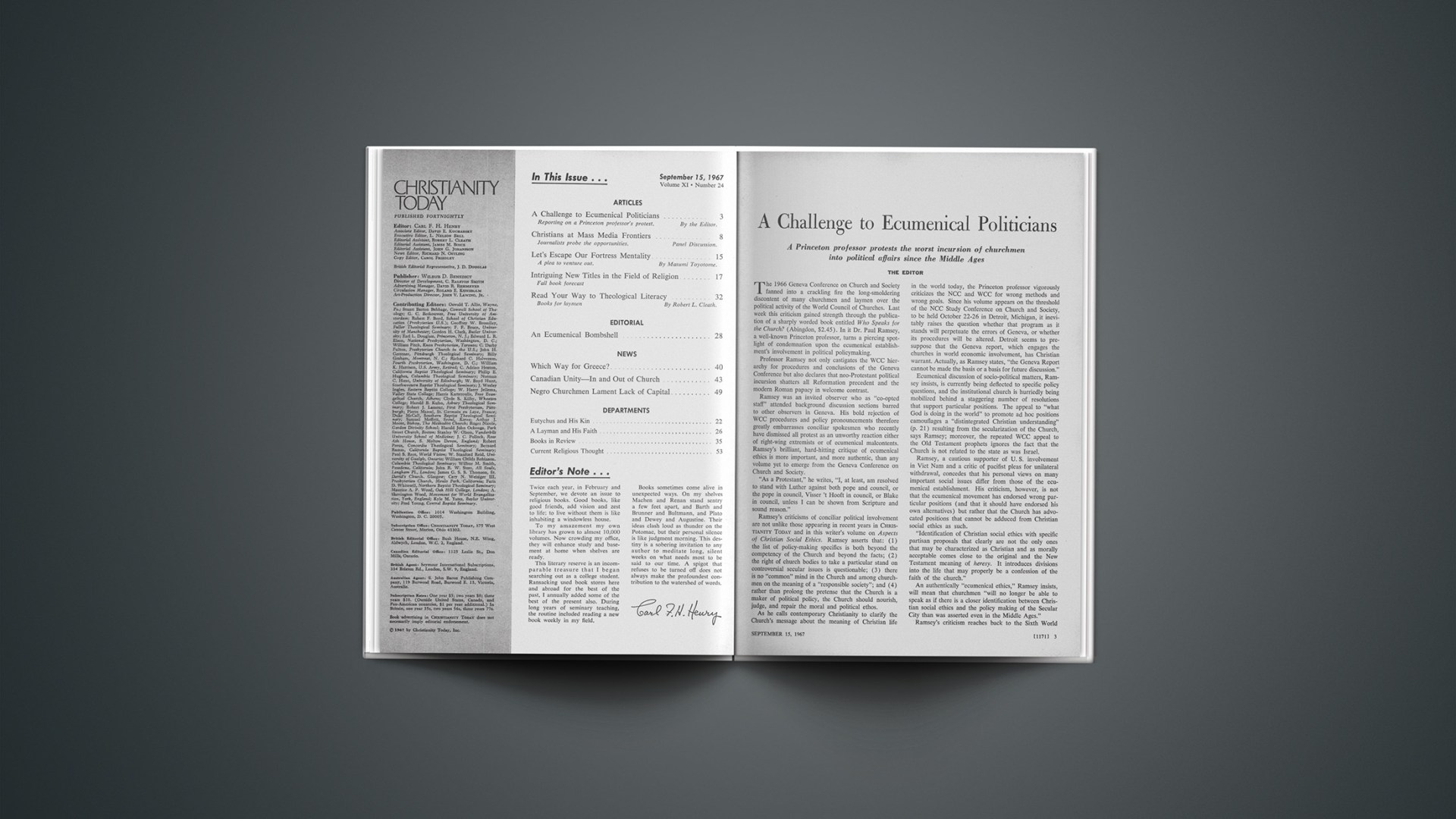

A Princeton professor protests the worst incursion of churchmen into political affairs since the Middle Ages

THE EDITOR

The 1966 Geneva Conference on Church and Society fanned into a crackling fire the long-smoldering discontent of many churchmen and laymen over the political activity of the World Council of Churches. Last week this criticism gained strength through the publication of a sharply worded book entitled Who Speaks for the Church? (Abingdon, $2.45). In it Dr. Paul Ramsey, a well-known Princeton professor, turns a piercing spotlight of condemnation upon the ecumenical establishment’s involvement in political policymaking.

Professor Ramsey not only castigates the WCC hierarchy for procedures and conclusions of the Geneva Conference but also declares that neo-Protestant political incursion shatters all Reformation precedent and the modern Roman papacy in welcome contrast.

Ramsey was an invited observer who as “co-opted staff” attended background discussion sections barred to other observers in Geneva. His bold rejection of WCC procedures and policy pronouncements therefore greatly embarrasses conciliar spokesmen who recently have dismissed all protest as an unworthy reaction either of right-wing extremists or of ecumenical malcontents. Ramsey’s brilliant, hard-hitting critique of ecumenical ethics is more important, and more authentic, than any volume yet to emerge from the Geneva Conference on Church and Society.

“As a Protestant,” he writes, “I, at least, am resolved to stand with Luther against both pope and council, or the pope in council, Visser’t Hooft in council, or Blake in council, unless I can be shown from Scripture and sound reason.”

Ramsey’s criticisms of conciliar political involvement are not unlike those appearing in recent years in CHRISTIANITY TODAY and in this writer’s volume on Aspects of Christian Social Ethics. Ramsey asserts that: (1) the list of policy-making specifics is both beyond the competency of the Church and beyond the facts; (2) the right of church bodies to take a particular stand on controversial secular issues is questionable; (3) there is no “common” mind in the Church and among churchmen on the meaning of a “responsible society”; and (4) rather than prolong the pretense that the Church is a maker of political policy, the Church should nourish, judge, and repair the moral and political ethos.

As he calls contemporary Christianity to clarify the Church’s message about the meaning of Christian life in the world today, the Princeton professor vigorously criticizes the NCC and WCC for wrong methods and wrong goals. Since his volume appears on the threshold of the NCC Study Conference on Church and Society, to be held October 22–26 in Detroit, Michigan, it inevitably raises the question whether that program as it stands will perpetuate the errors of Geneva, or whether its procedures will be altered. Detroit seems to presuppose that the Geneva report, which engages the churches in world economic involvement, has Christian warrant. Actually, as Ramsey states, “the Geneva Report cannot be made the basis or a basis for future discussion.”

Ecumenical discussion of socio-political matters, Ramsey insists, is currently being deflected to specific policy questions, and the institutional church is hurriedly being mobilized behind a staggering number of resolutions that support particular positions. The appeal to “what God is doing in the world” to promote ad hoc positions camouflages a “distintegrated Christian understanding” (p. 21) resulting from the secularization of the Church, says Ramsey; moreover, the repeated WCC appeal to the Old Testament prophets ignores the fact that the Church is not related to the state as was Israel.

Ramsey, a cautious supporter of U. S. involvement in Viet Nam and a critic of pacifist pleas for unilateral withdrawal, concedes that his personal views on many important social issues differ from those of the ecumenical establishment. His criticism, however, is not that the ecumenical movement has endorsed wrong particular positions (and that it should have endorsed his own alternatives) but rather that the Church has advocated positions that cannot be adduced from Christian social ethics as such.

“Identification of Christian social ethics with specific partisan proposals that clearly are not the only ones that may be characterized as Christian and as morally acceptable comes close to the original and the New Testament meaning of heresy. It introduces divisions into the life that may properly be a confession of the faith of the church.”

An authentically “ecumenical ethics,” Ramsey insists, will mean that churchmen “will no longer be able to speak as if there is a closer identification between Christian social ethics and the policy making of the Secular City than was asserted even in the Middle Ages.”

Ramsey’s criticism reaches back to the Sixth World Order Study Conference (St. Louis, 1965), a conclave that in addressing the political scene exceeded what could clearly be said “on the basis of Christian truth and insights.” Such statements adopt “a pose of being prophetic in criticism of present policy and in support of some alternate policy” although they involve churchmen beyond their competence and arrogate to the Church decisions that belong to the state. What these churchmen offer to modern statesmen is not the “political wisdom” of the Church but a biased reading of the issues in the interest of some particular line of action.

Ramsey scorns the notion of some leading ecumenists that their “specific-policy-making exercises are events in salvation history.” The Church and Society Syndrome, as he depicts it, assumes that “satyrlike statements of moral fact” are “within the scope of prophecy and precise preaching, and within the competence of Christian deliberation.… Unless statements of ethico-political principle are distinguished from specific applications the integrity of the secular office of political prudence is clouded.”

“Protestantism, especially, has today conjoined assertedly momentary prophetic response to God’s will and action with concrete political decision making, to the confusion of all distinctions concerning what can and what cannot be said in Christ’s name. This is confusion of terms and of competencies that has replaced … the various mixtures of ‘church’ and ‘state’ that formerly prevailed.”

The shrewd device of declaring that a select group of churchmen speak only for themselves and not for the Church encourages irresponsible utterances, Ramsey says; what churchmen say to the Church and to the world ought to be governed, rather, by Christian truth. What impresses the communications media and the public is not preliminary NCC General Board disavowals that it speaks for all Christians but the specific proposals about military strategy and political specifics. As Ramsey puts it: “What goes out to the world is a particular statement that will have the same actual or aspired influence on public policy as if it had been unanimous, and as if it had been asserted to be the Christian thing to do.”

Behind The Scenes At Geneva

Professor Ramsey’s critique surveys both the theology and the methodology of the Geneva Conference on Church and Society and evaluates its specific commitments on Viet Nam and on nuclear war. Were the procedures adequate for reaching responsible conclusions? In what was billed as a “study conference,” he remarks, the “major miracle” occurred that 410 people in two weeks drew up 118 paragraphs of conclusions—and precisely the conclusions, moreover, that would provide the “American curia” with apparent world ecumenical support for promoting its predetermined prejudices.

The Geneva “study conference” procedures, Ramsey states, actually were largely a revision of WCC policy conference procedures in New Delhi, and only a “semantic distinction” may be drawn between reports sent to the churches for study, resolutions to the churches, and conclusions. President John C. Bennett of Union Theological Seminary insisted that rather than simply transmitting reports to the WCC for study, consideration, and consequent action, the conference adopt conclusions to publicize its statements (press coverage was prearranged for the final plenary sessions).

Ramsey notes “the prima facie lack of adequate deliberation” to sustain the numerous findings. By the time subsections were less than midway into their discussions, they had to devote their sessions to preparing reports for correlation with conclusions. “The conference was simply not a deliberative body.… There was nothing very dialogic about it.” In discussing 118 complex and often specific judgments on crucial world problems, the 410 participants managed to produce 160 single-spaced mimeographed pages of material. In the actual sessions, debate was limited to the most controversial issues, and a five-minute time limit for comment was soon cut to three. Never did more than half the registered participants vote on such issues.

Ramsey does not raise the question why these 418 participants were assembled in Geneva, and not others. He does assert, however, that the American curia made its weight felt in the political pressures of the conference, and that observers readily noted the atmosphere of a political convention. Although more laymen than churchmen were invited, the uninvited included precisely those Christian laymen who are decision-makers in the middle echelon of government.

The shallow commitments hurriedly pushed through Geneva, from the plea for inclusion of Red China in the United Nations to the plea that the U. N. place Rhodesia under economic siege, are unworthy of being labeled serious Christian reflection, Ramsey adds. “That the section … or conference plenaries said anything after deliberation is a chimera and a procedural hoax. No one should even cite the authority of Geneva 1966.”

The Geneva verdict that U. S. military engagement in Viet Nam is unjustifiable was inspired, says Ramsey, by certain American churchmen and others of like sympathy. The initial draft committee even included an observer hostile to American policy. Of the committee draft Ramsey remarks, “One can discern … the fine hand of John Bennett in these paragraphs taken as a whole.” The four members of the committee were: President Bennett of Union Theological Seminary; Metropolitan Nicodim of the Bulgarian Orthodox Church; a Lebanese lawyer; an Indian businessman (an observer).

Ramsey, in fact, gives such penetrating criticisms of the Geneva commitments and provides such balancing factors that one wonders why this point of view was denied effective platform presentation by the Church and Society engineers and was unrepresented on the committee. Not only does he critically analyze a one-sided telegram sent to President Johnson by Geneva participants; he also deplores a telegram sent to the foreign minister of North Viet Nam over the name of Jon L. Regier, NCC associate general secretary for Christian life and mission (this division supervises the Department of International Affairs as well as a special action-for-peace group led by Robert Bilheimer). This telegram to North Viet Nam, which was signed by seventy-five Americans at the Geneva meeting, protested U. S. involvement in Viet Nam and any escalation of the conflict.

Ramsey On Political Ecumenism

The oddity is that contemporary ecumenical social ethics evidences less acknowledgment of the separation between the church and the office of magistrate or citizen than was clearly acknowledged by the great cultural churches of the past—except perhaps by the claims made by the bull Unum Sanctum (Boniface VIII, November 18,1302).

This is, indeed, the most barefaced secular sectarianism and but a new form of culture-Christianity. It would identify Christianity with the cultural vitalities, with the movement of history, with where the action is, with the next and even now the real establishment.…

We should be resolved to say no more about responsibility in society until we have done something about responsible deliberation, and the procedures necessary for this to be made possible, at conferences sponsored by the churches, the NCC and the WCC. I at least would not be able to sleep nights if I thought that decisions of my government concerning problems of middle-range importance and urgency were resolved as rapidly and carelessly and necessarily with as little debate as the Geneva conference presumed to teach particular conclusions of earthshaking importance—which with unnoticed irony often implied irresponsibility on the part of one or another government.

As a Protestant, I, at least, am resolved to stand with Luther against both pope and council, or the pope in council, Visser ’t Hooft in council, or Blake in council, unless I can be shown from Scripture and sound reason.

There is nothing wrong with “dialogue” except that this is not the way to promote it; nor responsible deliberation either, except that this was not it.

A Christian theologian or ethicist would have to be out of his mind to regard the working group paper on “Theological Issues in Social Ethics” produced at the Geneva conference as the basis (or even a basis) for future discussion in any other than the trivial sense that it may on occasion be useful to start talking.

Unless it can be made clear in what way Christian teaching can as such substantively and compellingly lead to these conclusions then this is simply to put the engine of religious fervor behind a particular partisan political point of view which would have as much or as little to recommend it if it had not emanated from a church council.…

The shrewdest device yet for accomplishing this purpose is the reservation that the resolutions and pronouncements on all sorts of subjects advising the statesman what he should do which issue from church councils (or from groups like the Clergy Concerned over Vietnam) in fact do not represent “the church” (or Christian morality) but only the views of the churchmen who happen to be assembled.… They are not in the position of the statesman who has to correct one policy by another and to bear the responsibility for any cost/benefits he may have left out of account. One can scarcely imagine a situation that to a greater extent invites irresponsible utterance.…

Radical steps need to be taken in ecumenical ethics if ever we are to correct the pretense that we are makers of political policy and get on with our proper task of nourishing, judging, and repairing the moral and political ethos of our time.

To pay attention to the distinctive and basic features of Christian social ethics … would make for a proper hesitation in faulting the consciences of our fellow Christians.…

Some may say, this critique of ecumenical social ethics is directed against an abuse of a basically correct undertaking in and among the churches. My thesis, however, is that the abusus (policy directives) has become usus—it has become the fashion—and that one will not sense the strength of the case for a radical reformation in the aims of church social teachings unless he begins by acknowledging this to be true.

Their task should be the nurture of a Christian ethos within the autonomies of the modern world, and not by manifold thought and action to attenuate that ethos still more by eliding it into worldly wisdom.

Prudential political advice comes into the public forum with no special credentials because it issues from Christians or from Christian religious bodies.

Does the older ecumenical movement hope to transcend the peoples among whom Christians are mingled in this world, not in the direction of clearer statement of Christian action-relevant perspectives upon the world’s problems, but in the direction of a universal view of concrete political policies for the world’s statesmen?

For ecumenical councils on Church and Society responsibly to proffer specific advice would require that the church have the services of an entire state department.

The Geneva condemnation of nuclear war (“nuclear war is against God’s will”), asserts Ramsey, does not “push very far into the nuclear problem or the responsibility of governments in the use of power for peace and justice in a nuclear age.” The condemnation, he points out, could be read as a sweeping indictment not only of unlimited destruction but of any use of nuclear weapons in any war, even for deterrence—and that, says Ramsey, “would be impossible and morally wrong.” Geneva stressed proportion of force to rule out nuclear power; the Vatican Council by contrast stressed discrimination.

Ramsey reveals that in the formulation of the Church’s point of view on peace in a nuclear age, not a single participant from any of the world’s four nuclear powers was included among the conference speakers on this theme. The only positive analysis was by the West Berlin theologian Helmut Gollwitzer, champion of nuclear pacifism, who declared that there is “general agreement” that the tests of justice in war have lost validity (their validity was apparently presupposed, however, says Ramsey, when it came to condemning the U. S. role in Viet Nam).

Ramsey characterizes the theological working group at Geneva as “a homeless waif.” He criticizes the paper on “Theological Issues in Social Ethics” on both procedural and substantive grounds and deplores its “mini-Christian analysis” of world problems. Speakers, he observes, had more to say about revolution and its relevance than about theology. What theology there was, was mainly a “truncated Barthianism”—Christological-eschatological dynamic monism, to use the lingo of the professionals. On the one hand, “creation” was reduced to the processes of historicized “nature”; on the other, Christ’s “ever coming present triumph over the powers” was emphasized. The “contextual revolutionary-Christocentric eschatologism” of Geneva collides with mainstream ecumenical theology and with Roman Catholic theology, contends Ramsey, which emphasize the sequence of Creation-Law-Gospel and look for Christ’s triumph over all powers only at the end of the age.

The Decline Of Ecumenical Ethics

So radical has been the shift of orientation in ecumenical ethics that today, Ramsey says, not only do the NCC and WCC alter their own traditional stance, but they also relate to an authentic Christian ethic far less constructively than does the church of Rome. “Not even the ‘magisterium’ of the Roman Catholic Church has in recent centuries, if ever, gone so far in telling statesmen what is required of them.”

Even the older “Faith and Order” models are far superior to the present “Church and Society” image. During the past fifteen years, Faith and Order discussions have experienced a kind of renewal through a concern with basic questions that determine the whole of theology, says Ramsey. But Dr. W. A. Visser’t Hooft, in his farewell address as general secretary of the WCC, defended the right of church bodies to take a specific stand on controversial social and political issues.

Ramsey approves the way in which Vatican Council II and also John XXIII spoke with socio-political relevance; they pointed directions without ecclesiastically binding the conscience of statesmen, quite in contrast to neo-Protestant ecumenists’ practice of addressing specific directives to political leaders. He commends the social encyclicals of John XXIII, the addresses of Paul VI, and the affirmations of Vatican II for not presuming ecclesiastical competence in policy-making. Although many ecumenists proclaim the end of the Protestant era, they display less ability than Rome, Ramsey suggests, to distinguish church from state, and assume competence to formulate detailed answers to all public questions.

The Church’s attempt to avoid mere “counsels of perfection” by adducing particular policy formulations, Ramsey continues, not only leads to a miscarriage of Christian ethics but also betrays churchmen into supporting bare abstractions. The Church’s pushing of a specific course of action upon a statesman, in the absence of a comprehensive framework of political policy, is as much a matter of useless advice as is political generality: “A bag of specifics is still a generality in relation to actual policy” (p. 29). Equally useless is the alternative of specifically condemning a present course of action and then offering only some indefinite generality as an alternative—advice to “end the bombing,” for example.

But an even worse prospect, warns Ramsey, is that ecumenical politicians may view the Church as “a surrogate world political community” with its own “shadow state department” that tells the governments of the world what to do. Some churchmen, in fact, contend that the Church’s stature in political involvement should be improved through the drafting of more “experts” to address ecumenical specifics to the world. But “it is the aim of specificity in the church’s resolutions and proclamations that should be radically called in question.” And even if the Church were to draft experts, says Ramsey, since the experts themselves disagree, the ecumenical curia could still be expected to protect its own prejudices.

For many years ecumenical politicians have demeaned as deficient in social conscience all evangelical critics of their policy-making intrusions into secular affairs. Professor Ramsey speaks not only from within the conciliar movement as an active Geneva participant but also as a member of the American Society of Christian Ethics and as an author of numerous books in the field of morals. Already one spokesman for the WCC hierarchy has privately remarked that Ramsey lacks the humility to conform his views to the weightier opinions of fellow ecumenical theologians. What neo-Protestant Christianity may now be expected to witness, therefore, is either a bolder assertion of the infallibility of the ecumenical curia or a deeper testing of the ability of ecumenical politicians to foist their personal biases upon secular leaders in the name of the Protestant churches.