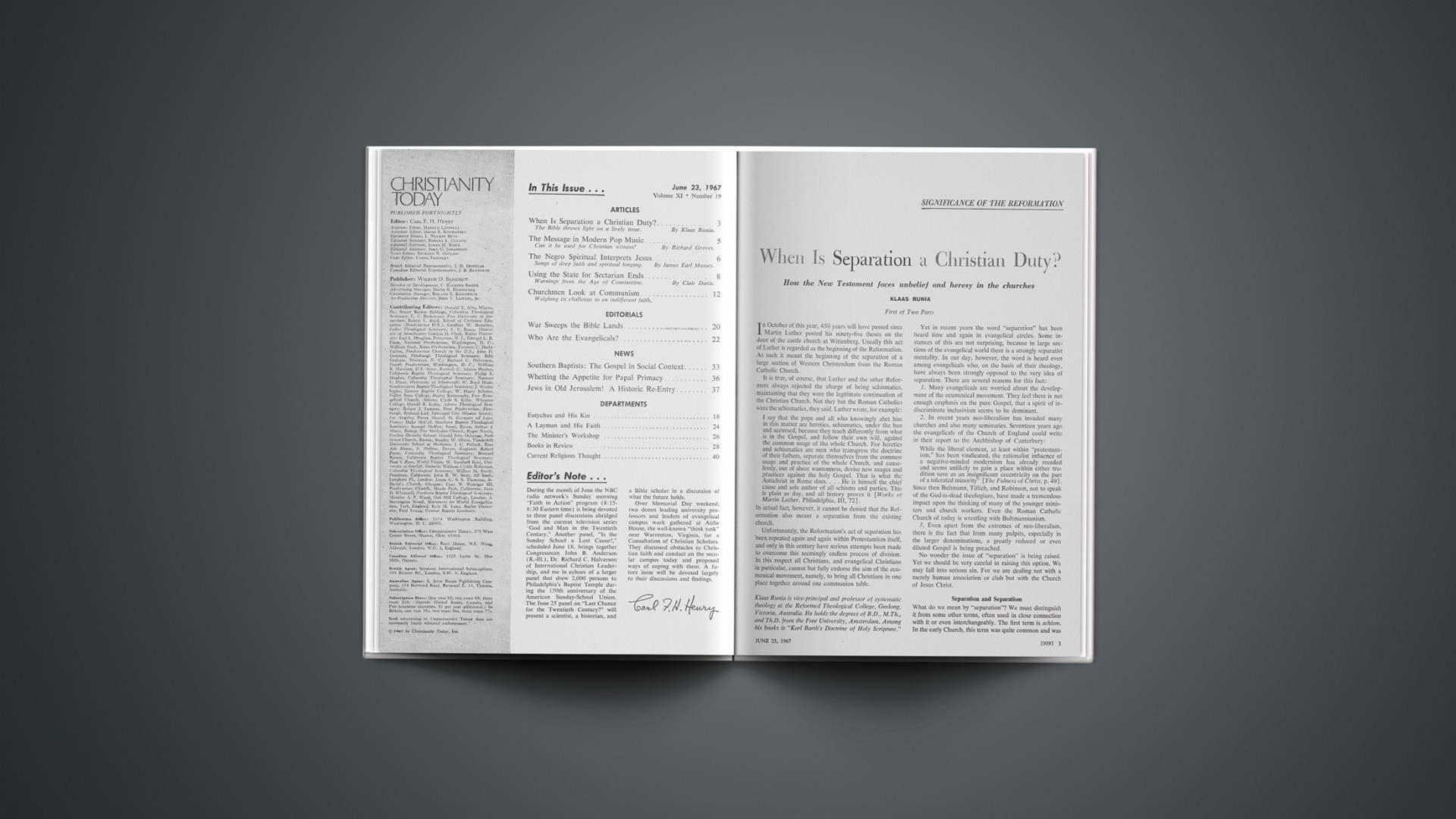

How the New Testament faces unbelief and heresy in the churches

First of Two Parts

In October of this year, 450 years will have passed since Martin Luther posted his ninety-five theses on the door of the castle church at Wittenberg. Usually this act of Luther is regarded as the beginning of the Reformation. As such it meant the beginning of the separation of a large section of Western Christendom from the Roman Catholic Church.

It is true, of course, that Luther and the other Reformers always rejected the charge of being schismatics, maintaining that they were the legitimate continuation of the Christian Church. Not they but the Roman Catholics were the schismatics, they said. Luther wrote, for example:

I say that the pope and all who knowingly abet him in this matter are heretics, schismatics, under the ban and accursed, because they teach differently from what is in the Gospel, and follow their own will, against the common usage of the whole Church. For heretics and schismatics are men who transgress the doctrine of their fathers, separate themselves from the common usage and practice of the whole Church, and causelessly, out of sheer wantonness, devise new usages and practices against the holy Gospel. That is what the Antichrist in Rome does.… He is himself the chief cause and sole author of all schisms and parties. This is plain as day, and all history proves it [Works of Martin Luther, Philadelphia, III, 72].

In actual fact, however, it cannot be denied that the Reformation also meant a separation from the existing church.

Unfortunately, the Reformation’s act of separation has been repeated again and again within Protestantism itself, and only in this century have serious attempts been made to overcome this seemingly endless process of division. In this respect all Christians, and evangelical Christians in particular, cannot but fully endorse the aim of the ecumenical movement, namely, to bring all Christians in one place together around one communion table.

Yet in recent years the word “separation” has been heard time and again in evangelical circles. Some instances of this are not surprising, because in large sections of the evangelical world there is a strongly separatist mentality. In our day, however, the word is heard even among evangelicals who, on the basis of their theology, have always been strongly opposed to the very idea of separation. There are several reasons for this fact:

1. Many evangelicals are worried about the development of the ecumenical movement. They feel there is not enough emphasis on the pure Gospel, that a spirit of indiscriminate inclusivism seems to be dominant.

2. In recent years neo-liberalism has invaded many churches and also many seminaries. Seventeen years ago the evangelicals of the Church of England could write in their report to the Archbishop of Canterbury:

While the liberal element, at least within “protestantism,” has been vindicated, the rationalist influence of a negative-minded modernism has already receded and seems unlikely to gain a place within either tradition save as an insignificant eccentricity on the part of a tolerated minority” [The Fulness of Christ, p. 49].

Since then Bultmann, Tillich, and Robinson, not to speak of the God-is-dead theologians, have made a tremendous impact upon the thinking of many of the younger ministers and church workers. Even the Roman Catholic Church of today is wrestling with Bultmannianism.

3. Even apart from the extremes of neo-liberalism, there is the fact that from many pulpits, especially in the larger denominations, a greatly reduced or even diluted Gospel is being preached.

No wonder the issue of “separation” is being raised. Yet we should be very careful in raising this option. We may fall into serious sin. For we are dealing not with a merely human association or club but with the Church of Jesus Christ.

Separation And Separatism

What do we mean by “separation”? We must distinguish it from some other terms, often used in close connection with it or even interchangeably. The first term is schism. In the early Church, this term was quite common and was often used in close relation to the word “heresy.” In fact, at first the two were almost identical, as we see in First Corinthians 11:18, 19, where “divisions” (schismata) and “factions” (haireseis) are almost used as synonyms. Gradually, however, the ancient Church distinguished the two, using heresy to mean false doctrine and schism an orthodox sect. In other words, schism in its original meaning always refers to a division in the church that is due to causeless differences and contentions among its members. The separating party leaves a church that is itself still faithful to the Gospel.

Separation denotes a different situation. Here a group separates itself from the main body because that body has become unfaithful to the Word of God. It is unfortunate that often any separation is simply termed a “schism.” To mention an example, the breach between the churches of the East and West in 1054 and the following centuries was clearly a schism. There were no real doctrinal differences (apart from the “filioque” question). The Reformation of the sixteenth century was not a schism (at least not from the point of view of the Reformers) but rather a separation. The same can be said of several secessions in the nineteenth century, as, for example, in 1834 and 1886 in the Netherlands. Often, in the case of separation, those who leave the church are forced out by the parent body.

Separation must also be distinguished from separatism. This term denotes the ecclesiology and practical attitude of those who leave their church prompted by a wrong spirit. Separatists make no attempt to reform the church from within, nor do they have any understanding of or concern for the visible unity of the church; instead, they are motivated by some form of ecclesiological perfectionism that compels them to abandon the existing church and establish a new one. I have no appreciation whatever for any form of separatism, even if I share its concern for the purity of the church.

A Biblical Answer

But what of separation? Is it ever permitted? Are there any objective norms?

Naturally we must concentrate on the New Testament. Yet we cannot completely bypass the Old Testament. Those who condemn all separation often appeal to the Old Testament on two points. First, they point to the attitude of the prophets, who, in spite of the terrible corruption of the church of their days, never separated from it in order to establish a new people of God with a separate cult. In my opinion, however, this argument is completely untenable, for it loses sight of the peculiar situation of Israel as the theocratic nation of God. The application of the national-church (Volkskirche) idea to the New Testament church by the Reformers of the sixteenth century and by many defenders of the established-church concept in our own day not only is without any scriptural warrant, but also has led to an externalization of the church.

A second argument against separation is at times derived from the Old Testament concept of the remnant. As the Old Testament church was preserved in the faithful remnant, it is said, so true believers have a duty to preserve the church today by staying in it. However plausible this argument may seem at first glance, it is based on a complete misunderstanding of the Old Testament concept. A. Lelièvre rightly states:

After the resurrection, the culmination of the history of salvation precludes the principle of the remnant. In this respect the Acts is especially clear and significant in its allusion to ever-increasing numbers.… There can no longer be this movement of reduction in the case of the new covenant, for it is a movement which is entirely characteristic of the Old Testament: it is a pattern inherent in the process by which the coming of Christ is prepared. The Christian Church is not the remnant, but rather the new humanity of the future springing from the remnant which Jesus Christ embodied in his own person [von Allmen, Vocabulary of the Bible, p. 356].

It is evident that every application of the concept to the New Testament church, and in particular to the true believers in a corrupted church, reveals a historical misunderstanding.

The New Testament condemns all unnecessary schism (1 Cor. 1:10 ff.; 11:18, 19; Gal. 2:12). All such schisms are “works of the flesh” (Gal. 5:20). Throughout the whole New Testament there is a tremendous emphasis on the unity of the church.

Yet there are also other aspects that may not be ignored. First, there is the fact that gradually the New Testament church separates itself from the Jewish church. It is a rather slow process; but it is inevitable, because Israel as a nation refuses to accept Jesus as the Messiah. In fact, because of its opposition to Christ it actually becomes the “synagogue of satan” (Rev. 2:9), while the New Testament church is seen as the true “Israel of God” (Gal. 6:16).

Secondly, there is the teaching of Second Corinthians 6:14–17. This passage has often been used by separatists as a direct commandment of the Lord to separate from a church that has become unfaithful, but this application is not warranted. Paul is not speaking of the church but of the world. Hodge, in his commentary, rightly notes that the “Hoi apistoi are the heathen.” Yet he also points out that the principle has a wider application. “The principle applies to all the enemies of God and children of darkness.” How it has to be applied in the case of an unfaithful church must be decided by the teaching of the whole New Testament. A straightforward appeal to verse seventeen (“Therefore, come out from them and be separate from them”) in defense of separatism is an oversimplification of the issue.

Of much more importance for our subject is a third aspect of New Testament teaching, the clear commandment that heresy is not to be tolerated in the church. Throughout the New Testament, heresy is condemned in the strongest terms and believers are told to separate themselves from heretics. This separation, however, is accomplished not by the believers’ withdrawal from the church, but by the expulsion of the heretic (Gal. 1:8, 9; 2 Tim. 3:5; Tit. 3:10, 11; 1 John 4:1 ff.; 2 John 7–11; Rev. 2:14).

This, I believe, is the sum of the direct teaching of the New Testament on our subject. The results are rather meagre; but this is not surprising, for the New Testament does not know our situation! Although W. Elert is right when he says of the false teachers in Paul’s days: “From the apostle’s warning we must conclude that the false apostles had established themselves in the congregation,” he is equally right when he adds that Paul disposed of them, making his decision “on the basis of his apostolic authority” (Eucharist and Church Fellowship in the First Four Centuries, pp. 48, 49). Only after the days of the New Testament did heresy gain a foothold in the church.

Does this mean that we have no biblical norm for our present-day problems? Definitely not! The New Testament remains normative also for our subject. It does not deal directly with our questions, but indirectly it gives the final answer by what it says about the true nature of the church and its unity. We should never make the mistake of isolating the problem of “separation.” It is an aspect of a much wider question. [To be Continued]