This is a rallying cry for evangelicals everywhere. It is addressed to millions of evangelicals in mainstream Protestantism who chafe under the debilitating restraints of conciliar ecumenism and are frustrated by its lack of biblical challenge, and to additional millions who witness as best they can from the fragmented fringes of independency.

To all these we plead, “Somehow, let’s get together!”

There are signs of a fresh longing, particularly among younger evangelicals, for dramatic new dimensions of fellowship across denominational lines. Increasingly the need becomes evident for a greater framework of cooperation as evangelicals seek to witness to the world of the sovereignty of Christ. The fullest possible impact of evangelical Christianity upon the world in the remaining portion of the twentieth century can come only through coordinated effort.

This is not to say that evangelicals now lack a conscious identity. There is no more recognizable bloc in all of Protestantism, despite their mass-media invisibility. Their common ground is belief in biblical authority and in individual spiritual regeneration as being of the very essence of Christianity. They are people of the Book, alive to God’s good news.

But this common ground is crisscrossed by many fences. Evangelicals differ not only on secondary doctrines but also on ecclesiology, the role of the Church in society, politics, and cultural mores. No honest observer would minimize the extent to which they are divided.

Yet are not Bible-believing Christians called to rise above these differences in the interest of winning lost men and women to Christ? And if the Scriptures exhort believers to Christian unity, can these differences really be thought insurmountable? If evangelicals keep the Bible in the forefront of their preaching, what are they to do with its emphasis on unity and its requirement of all-encompassing evangelical loyalty to Jesus Christ?

I therefore … beseech you that ye walk worthy of the vocation wherewith ye are called, with all lowliness and meekness, with longsuffering, forbearing one another in love; endeavoring to keep the unity of the Spirit in the bond of peace. There is one body, and one Spirit, even as ye are called in one hope of your calling; one Lord, one faith, one baptism, one God and Father of all, who is above all, and through all, and in you all [Eph. 4:1–6].

Paul’s classic passage on Christian unity loses no inspiration or authority because conciliar ecumenists appeal to it ad infinitum to promote mergers and remergers in the absence of renewal. Independent evangelicals intensely fear an inclusive church, and for this reason their preachers often ignore the theme of unity; yet this passage remains as much God’s Word as John 3:16—and no Christian dare neglect it.

Evangelicals tend to emphasize the spiritual unity they already have, not organizational and structural prospects for the future. They prize a unity, moreover, that has its focus not merely on subjective considerations but on the objective realities of the Christian faith. Yet they are increasingly impelled to ask whether, in an age of diminishing denominational loyalties, they may not also need some more visible framework through which to confront the world with the Gospel.

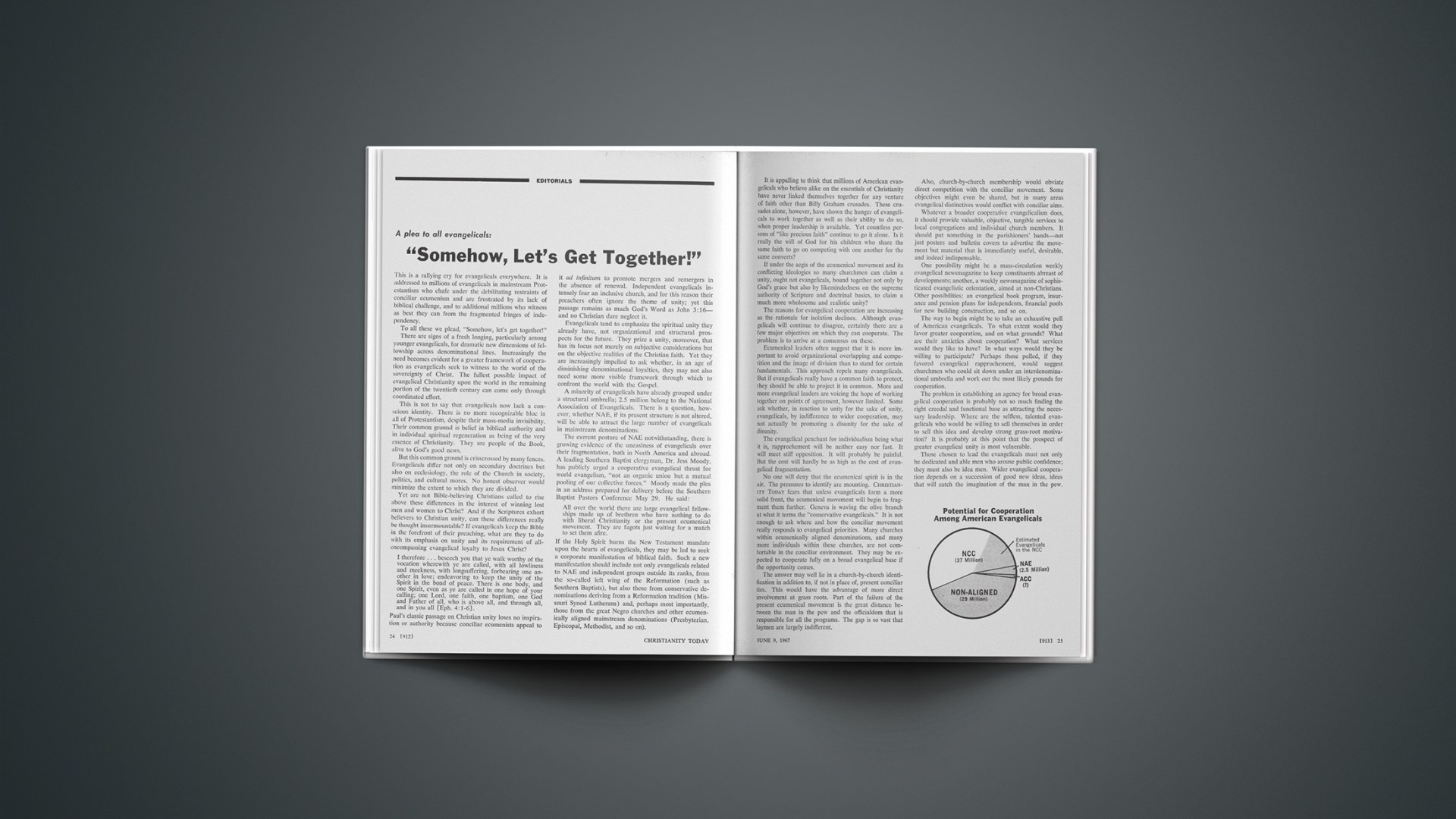

A minority of evangelicals have already grouped under a structural umbrella; 2.5 million belong to the National Association of Evangelicals. There is a question, however, whether NAE, if its present structure is not altered, will be able to attract the large number of evangelicals in mainstream denominations.

The current posture of NAE notwithstanding, there is growing evidence of the uneasiness of evangelicals over their fragmentation, both in North America and abroad. A leading Southern Baptist clergyman, Dr. Jess Moody, has publicly urged a cooperative evangelical thrust for world evangelism, “not an organic union but a mutual pooling of our collective forces.” Moody made the plea in an address prepared for delivery before the Southern Baptist Pastors Conference May 29. He said:

All over the world there are large evangelical fellowships made up of brethren who have nothing to do with liberal Christianity or the present ecumenical movement. They are fagots just waiting for a match to set them afire.

If the Holy Spirit burns the New Testament mandate upon the hearts of evangelicals, they may be led to seek a corporate manifestation of biblical faith. Such a new manifestation should include not only evangelicals related to NAE and independent groups outside its ranks, from the so-called left wing of the Reformation (such as Southern Baptists), but also those from conservative denominations deriving from a Reformation tradition (Missouri Synod Lutherans) and, perhaps most importantly, those from the great Negro churches and other ecumenically aligned mainstream denominations (Presbyterian, Episcopal, Methodist, and so on).

It is appalling to think that millions of American evangelicals who believe alike on the essentials of Christianity have never linked themselves together for any venture of faith other than Billy Graham crusades. These crusades alone, however, have shown the hunger of evangelicals to work together as well as their ability to do so, when proper leadership is available. Yet countless persons of “like precious faith” continue to go it alone. Is it really the will of God for his children who share the same faith to go on competing with one another for the same converts?

If under the aegis of the ecumenical movement and its conflicting ideologies so many churchmen can claim a unity, ought not evangelicals, bound together not only by God’s grace but also by likemindedness on the supreme authority of Scripture and doctrinal basics, to claim a much more wholesome and realistic unity?

The reasons for evangelical cooperation are increasing as the rationale for isolation declines. Although evangelicals will continue to disagree, certainly there are a few major objectives on which they can cooperate. The problem is to arrive at a consensus on these.

Ecumenical leaders often suggest that it is more important to avoid organizational overlapping and competition and the image of division than to stand for certain fundamentals. This approach repels many evangelicals. But if evangelicals really have a common faith to protect, they should be able to project it in common. More and more evangelical leaders are voicing the hope of working together on points of agreement, however limited. Some ask whether, in reaction to unity for the sake of unity, evangelicals, by indifference to wider cooperation, may not actually be promoting a disunity for the sake of disunity.

The evangelical penchant for individualism being what it is, rapprochement will be neither easy nor fast. It will meet stiff opposition. It will probably be painful. But the cost will hardly be as high as the cost of evangelical fragmentation.

No one will deny that the ecumenical spirit is in the air. The pressures to identify are mounting. CHRISTIANITY TODAY fears that unless evangelicals form a more solid front, the ecumenical movement will begin to fragment them further. Geneva is waving the olive branch at what it terms the “conservative evangelicals.” It is not enough to ask where and how the conciliar movement really responds to evangelical priorities. Many churches within ecumenically aligned denominations, and many more individuals within these churches, are not comfortable in the conciliar environment. They may be expected to cooperate fully on a broad evangelical base if the opportunity comes.

The answer may well lie in a church-by-church identification in addition to, if not in place of, present conciliar ties. This would have the advantage of more direct involvement at grass roots. Part of the failure of the present ecumenical movement is the great distance between the man in the pew and the officialdom that is responsible for all the programs. The gap is so vast that laymen are largely indifferent.

Also, church-by-church membership would obviate direct competition with the conciliar movement. Some objectives might even be shared, but in many areas evangelical distinctives would conflict with conciliar aims.

Whatever a broader cooperative evangelicalism does, it should provide valuable, objective, tangible services to local congregations and individual church members. It should put something in the parishioners’ hands—not just posters and bulletin covers to advertise the movement but material that is immediately useful, desirable, and indeed indispensable.

One possibility might be a mass-circulation weekly evangelical newsmagazine to keep constituents abreast of developments; another, a weekly newsmagazine of sophisticated evangelistic orientation, aimed at non-Christians. Other possibilities: an evangelical book program, insurance and pension plans for independents, financial pools for new building construction, and so on.

The way to begin might be to take an exhaustive poll of American evangelicals. To what extent would they favor greater cooperation, and on what grounds? What are their anxieties about cooperation? What services would they like to have? In what ways would they be willing to participate? Perhaps those polled, if they favored evangelical rapprochement, would suggest churchmen who could sit down under an interdenominational umbrella and work out the most likely grounds for cooperation.

The problem in establishing an agency for broad evangelical cooperation is probably not so much finding the right creedal and functional base as attracting the necessary leadership. Where are the selfless, talented evangelicals who would be willing to sell themselves in order to sell this idea and develop strong grass-root motivation? It is probably at this point that the prospect of greater evangelical unity is most vulnerable.

Those chosen to lead the evangelicals must not only be dedicated and able men who arouse public confidence; they must also be idea men. Wider evangelical cooperation depends on a succession of good new ideas, ideas that will catch the imagination of the man in the pew. Anything less will be subject to dismissal as a reactionary movement.

Evangelicals have a lot going for them. Theirs is more than a church; it is Christianity with a cause. Evangelicals have a wide area of agreement on doctrinal essentials. They are the most active and aggressive of all Protestants. They have the highest per-capita giving. They turn out the most ministers and missionaries. They are the most faithful in prayer, in Bible study, and in witnessing to their faith.

Why ought not they also to be able to point to a tangible fellowship? Is it not time for evangelicals to stand up and be counted together for things that matter most, for a commitment to fulfill more perfectly Christ’s will “that they may be one, even as we are one”?

We urge laymen and clergy alike to speak up in their churches and to pray that God will see fit to call out initiators. We invite evangelical leaders to begin immediate discussion of the merits and methods of establishing wide cooperation. We hope that many evangelical editors will react to this editorial in their own pages. We trust that officials of all Christian organizations and mission boards will communicate with their constituencies and draw out opinions. And we solicit comment and criticism in the hope that responsible discussion will lead to action.

Some activist churchmen presume to equate left-wing political movements with God’s action in history

The steady stream of pontifical pronouncements on political, social, and economic matters from church officialdom gives the typical American the impression that the Christian Church assumes a position immediately adjacent to that of the left-wing Americans for Democratic Action. Liberal churchmen dedicated to the transformation of men through the restructuring of social institutions have effectively projected this image by numerous public demonstrations, frequent testimony at governmental hearings, and extensive use of the mass media.

But do these men really speak for the Church? A growing number of Christians do not think so. Recognizing the right of clergymen to hold and express personally their own political convictions, many church members nonetheless resent the audacious presumption of ecclesiastical activists who unhesitatingly equate their left-wing social and political movements with the action of God in history. They further criticize these spokesmen, who often are limited in socio-economic understanding, for their adamant refusal to consider seriously the idea that conservative positions may reflect equally well, if not better, the biblical perspective on complex issues of the world today.

The zeal with which liberal churchmen pursue social action—giving it a higher priority in their ministries than winning men to Christ through gospel preaching—may be traced to the current liberal theological tendency to regard contemporary evangelism as essentially political in nature. To achieve their objective of helping men to be “truly human,” they have committed themselves to massive action programs to reshape society. The policies that have emerged in such programs resemble those of socialist-tinged revolutionaries: castigation of the free-enterprise system, opposition to America’s anti-Communist policy in Viet Nam, support of disruptive civil-rights protesters, endorsement of libertarian sexual practices, and efforts to equalize men economically regardless of personal productivity. Church members have a valid basis for objecting to the fact that their religious leaders promote these views as if they represented a Christian consensus or were grounded in the truth of revelation.

The Church should not suppose that any human politico-socio-economic philosophy or program in itself embodies the Christian position. The complexity of issues in contemporary life supports the idea that differing viewpoints on these matters should be freely expressed within the Christian community. But none should be sanctioned, either by official action or by carefully planned propaganda techniques, as representative of the entire church, especially when the hierarchical spokesmen make no conscientious attempt to ascertain the mind of the laity.

The World Council of Churches has been criticized frequently and justly for usurping the authority to promote certain political, social, and economic policies in the name of the Church. WCC spokesmen usually answer that these policy statements speak to and not for the Church. The study booklet for the Fourth WCC Assembly in Uppsala admits, however, that the WCC Commission of the Church on International Affairs has consciously functioned as an instrument of political propaganda. The booklet states:

In the United Nations, in other diplomatic conferences, and in councils of governments, the Commission seeks to make known and win acceptance for views predominantly held within the World Council of Churches, relating to such matters as the cessation of nuclear weapons testing, disarmament, race relations, religious liberty, national independence, development and refugee needs, as well as currently critical issues such as Vietnam and Rhodesia.

Needless to say, the WCC has invariably endorsed left-wing policies.

Since the liberal stance of clerical activists is becoming popularly accepted as that of the whole Church, church members who oppose this political posture must let their Christian voices be heard. The pulpit should not become a political sounding board nor the congregational meeting a public political forum. But individual Christians involved in public affairs, particularly those in policy-making jobs, must speak out boldly, relating their views to Christian conscience. The world must be made to realize that the Christian community as such is vitally concerned that God’s will be done in public matters.

A graphic example of an individual Christian’s expressing a socio-economic opinion contrary to that of his denominational leaders was seen in the speech delivered by Clifford Anderson, a United Church of Christ layman from Glen Ridge, New Jersey, at the recent Kodak-FIGHT showdown in Flemington, New Jersey. After a complete personal investigation of the racial-economic issues in the controversy, Anderson dissented vigorously to the anti-Kodak position presented by United Church of Christ executive Howard E. Spragg. In his informed presentation supporting Kodak, he disspelled the notion that the church hierarchy spoke for the entire denomination. And, in our opinion, his view was far more Christian and sound.

The Church must always concentrate on proclaiming the good news of personal salvation in Christ. But through its individual members it must also bring the truth of Christ to bear in the social, economic, and political realms. Millions of Christians occupy strategic positions in government, business, labor, education, the professions, the arts, and other important fields where Christian social concerns need to be expressed. Let these people as well as the clergy utter their Christian convictions and thereby help to improve our nation and world. The eager ecclesiastical advocates of a single left-wing politico-socio-economic line must not be allowed, through the default of a silent laity, exclusive claim to the Church’s prestige to promote their social doctrines. Often their views must be opposed as decidedly anti-Christian. All Christians must assume their responsibility to support by voice and action those causes that are in keeping with the Gospel.

How is the voice of the Church heard? Surely it is not restricted to the declarations of a particular coterie of clerical activists. Rather, every Christian as a believer-priest has the obligation to make himself heard. Let him do so, enlightened by biblical teaching, armed with the facts, humble in attitude, and courageous in conviction. The man of faith who by word and deed discharges his Christian responsibilities in all realms of life will be used by Jesus Christ as he speaks his word of love and judgment to the world.

Mariolatry: No Bar To Unity?

Renewed emphasis on devotion to the Virgin Mary by Pope Paul VI as he commemorated the fiftieth anniversary of the reported visions at Fatima shows that the “infallible” leader of the Roman Catholic Church has no intention of abandoning this unbiblical doctrine in order to promote unity within Christendom. Obviously disturbed by the Pandora’s box of liberal teaching opened by Vatican II, the Pope sternly warned against “replacing the theology of the true and great fathers of the Church with new and peculiar ideologies.” He urged the faithful to renew their personal consecration to the “immaculate heart of Mary,” “demonstrating toward the Virgin Mother of God a more ardent piety and a more steadfast trust.” Rightly decrying other false teachings, he ironically went far beyond Vatican II in reaffirming the Marian heresy.

The Pope’s enthusiastic endorsement of Marian dogma, traditionally offensive to Protestants, seems no longer to be a barrier to Protestant-Catholic dialogue and cooperation. Five days later representatives of the World Council of Churches and a group of Roman Catholic leaders meeting at Ariccia, Italy, issued a communique recommending “that the WCC and the Catholic Church pursue a policy of more dynamic collaboration.” The study group, whose joint chairmen were WCC General Secretary Eugene Carson Blake and Bishop Jan Willebrands, secretary of the Vatican Secretariat for Promoting Christian Unity, gave special attention to “the particular obligation of cooperation in the field of service activities, economic justice and development, international affairs and peace.”

In the steadily growing rapprochement of the WCC and the Roman Catholic Church, the two gigantic international religious bodies are forging chains of cooperation primarily on the notion that the efforts of men will bring in the Kingdom of God. The WCC stresses human political action rather than proclamation of the Gospel, and the Roman Catholic Church relies upon manmade traditions and institutions rather than the New Testament principle of the Bible alone. Although their emphases are different, both rest on the fallible wisdom of man rather than the infallible wisdom and revealed truth of God. In view of the Pope’s recent reaffirmation of devotion to Mary and the WCC’s stepped-up program of politico-socio-economic action, Bible-believing Christians have good reason to be concerned about this “dynamic collaboration” that could all too easily lead to one great world church of man.

Post Mortem: Confession Of ’67

For 238 years the United Presbyterian Church has been guided and governed by the Westminster Confession of Faith and Catechism. Recently, after several turbulent years of debate, the General Assembly in anticlimactic fashion ratified the “Book of Confessions.” The Westminster Confession has now lost its unique and normative postion as guardian of the church’s theology.

The inclusion of the “Confession of 1967” in the “Book of Confessions” and the change of the subscription formula will benefit those clergymen who solemnly vowed adherence to the Westminster standards despite significant mental reservation. In these days of “confusion theology” many churchmen find it easy to swallow a mixture of conflicting viewpoints without getting indigestion.

We predict that the adoption of the new confession will sap the church’s spiritual vitality in the future. But we sincerely pray this prediction will prove wrong.