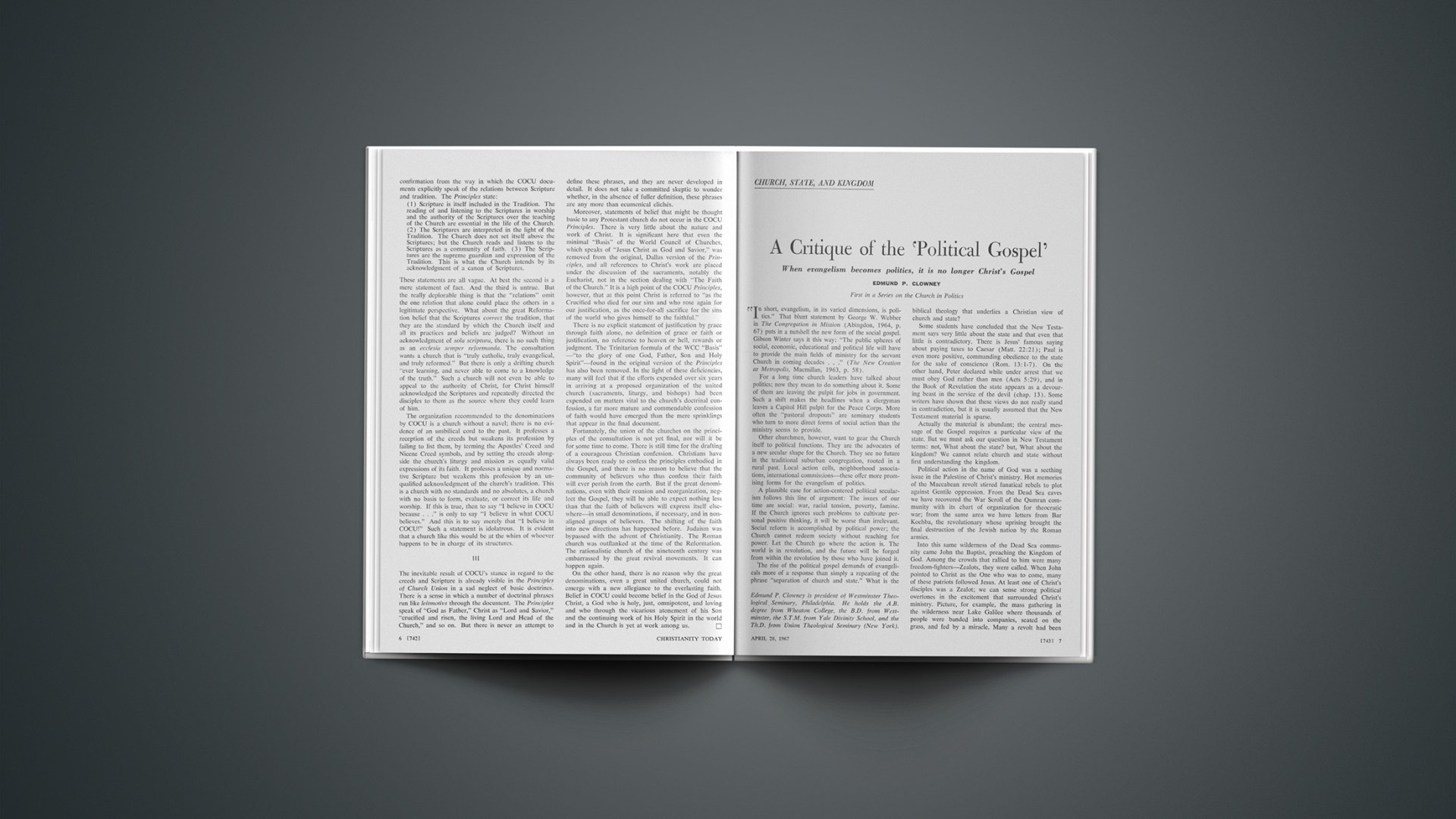

When evangelism becomes politics, it is no longer Christ’s Gospel

First in a Series on the Church in Politics

“In short, evangelism, in its varied dimensions, is politics.” That blunt statement by George W. Webber in The Congregation in Mission (Abingdon, 1964, p. 67) puts in a nutshell the new form of the social gospel. Gibson Winter says it this way: “The public spheres of social, economic, educational and political life will have to provide the main fields of ministry for the servant Church in coming decades …” (The New Creation as Metropolis, Macmillan, 1963, p. 58).

For a long time church leaders have talked about politics; now they mean to do something about it. Some of them are leaving the pulpit for jobs in government. Such a shift makes the headlines when a clergyman leaves a Capitol Hill pulpit for the Peace Corps. More often the “pastoral dropouts” are seminary students who turn to more direct forms of social action than the ministry seems to provide.

Other churchmen, however, want to gear the Church itself to political functions. They are the advocates of a new secular shape for the Church. They see no future in the traditional suburban congregation, rooted in a rural past. Local action cells, neighborhood associations, international commissions—these offer more promising forms for the evangelism of politics.

A plausible case for action-centered political secularism follows this line of argument: The issues of our time are social: war, racial tension, poverty, famine. If the Church ignores such problems to cultivate personal positive thinking, it will be worse than irrelevant. Social reform is accomplished by political power; the Church cannot redeem society without reaching for power. Let the Church go where the action is. The world is in revolution, and the future will be forged from within the revolution by those who have joined it.

The rise of the political gospel demands of evangelicals more of a response than simply a repeating of the phrase “separation of church and state.” What is the biblical theology that underlies a Christian view of church and state?

Some students have concluded that the New Testament says very little about the state and that even that little is contradictory. There is Jesus’ famous saying about paying taxes to Caesar (Matt. 22:21); Paul is even more positive, commanding obedience to the state for the sake of conscience (Rom. 13:1–7). On the other hand, Peter declared while under arrest that we must obey God rather than men (Acts 5:29), and in the Book of Revelation the state appears as a devouring beast in the service of the devil (chap. 13). Some writers have shown that these views do not really stand in contradiction, but it is usually assumed that the New Testament material is sparse.

Actually the material is abundant; the central message of the Gospel requires a particular view of the state. But we must ask our question in New Testament terms: not, What about the state? but, What about the kingdom? We cannot relate church and state without first understanding the kingdom.

Political action in the name of God was a seething issue in the Palestine of Christ’s ministry. Hot memories of the Maccabean revolt stirred fanatical rebels to plot against Gentile oppression. From the Dead Sea caves we have recovered the War Scroll of the Qumran community with its chart of organization for theocratic war; from the same area we have letters from Bar Kochba, the revolutionary whose uprising brought the final destruction of the Jewish nation by the Roman armies.

Into this same wilderness of the Dead Sea community came John the Baptist, preaching the Kingdom of God. Among the crowds that rallied to him were many freedom-fighters—Zealots, they were called. When John pointed to Christ as the One who was to come, many of these patriots followed Jesus. At least one of Christ’s disciples was a Zealot; we can sense strong political overtones in the excitement that surrounded Christ’s ministry. Picture, for example, the mass gathering in the wilderness near Lake Galilee where thousands of people were banded into companies, seated on the grass, and fed by a miracle. Many a revolt had been organized in the desert; King Herod, “that fox,” had just murdered John the Baptist; the people were ready to march on Jerusalem. They sought to make Jesus king by force.

When Christ was crucified by the Romans, the charge placarded on the cross was the title “King of the Jews.” Jesus was executed for alleged revolt against Caesar.

Yet the Kingdom of Jesus’ preaching was not what the Zealots expected. Viewed as organized political action, Jesus’ ministry was a total failure. He refused to be made a king; he chose a collaborator, a hated tax-collector, to be a disciple along with the Zealot; disillusioned crowds streamed away from him; one of his own followers betrayed him with a bitter kiss; when he died as a criminal, the royal title above him drew the laughter of the Jews and the contempt of the Romans.

What was the message of the Kingdom that seemed to baffle Jesus’ followers and infuriate his enemies? We have the nub of the issue in an agonized question sent by John the Baptist to Jesus from prison: “Art thou he that cometh, or look we for another?” (Luke 7:19, ASV). The question reveals that John’s expectation of the coming Kingdom was centered in the coming King.” He that cometh” reflects the phrasing of Psalm 118:26: “Blessed be he that cometh in the name of the Lord.” (See also Luke 19:38.) Indeed, John looked for a Messiah who not only came in the name of the Lord but also was identified with the Lord. John’s task was to prepare in the desert a highway for the coming Lord (Isa. 40:3; Mai. 3:1–3; Luke 3:4; John 1:30). He testified that the coming one would cleanse his people, baptizing with the Spirit and fire (Matt. 3:11, 12). The coming One was Lord, Judge, Deliverer, and would bring the axe and fire of judgment against every tree of wickedness and set the oppressed free.

John had preached urgent repentance before the coming Lord. But when Christ appeared, John faced new problems: Jesus insisted on being baptized by John, an action identifying him with the people rather than judging them. A dove descended from heaven upon him, but no fire. John continued to fast with his disciples, waiting for the fire, the axe of judgment. Jesus meanwhile led his disciples to a wedding feast. Then, as John continued his preaching of repentance, he was thrown in prison by Herod. In jail John heard of Jesus’ miracles. Wonderful signs they were, evidences of the power of the Kingdom. But they were miracles of blessing, not judgment. How could there be signs of the new age without the judgment that was to usher it in?

Jesus’ answer to John gives the key to understanding the Kingdom. John’s disciples see and hear of the signs of Christ’s power: he delivers men from sickness, casts out evil spirits, cleanses lepers, causes the blind to see, raises the dead, and preaches the Gospel to the poor. His word to John is to tell him what they have seen and heard and add, “Blessed is he, whosoever shall find no occasion of stumbling in me” (Luke 7:23, ASV).

Since John already knew of Christ’s miracles, how does reporting them answer his question? First, because the miracles show that the power of the Kingdom is at work. Christ has the authority to remove evil and deliver the captives of Satan. His power includes the conquest of death. Second, because the signs are signs of promise. They are gospel miracles, reflecting and fulfilling the promise of the prophets (Isa. 35:5–8; 61:1). The healing Lord (Ex. 15:26) is among his people, removing the evidence of the curse with signs of blessing. The good news of God’s great day of jubilee is being preached to the poor and the captive (Luke 4:18, 19). What is given in sign is present in the Lord who gives the sign. John must therefore trust in him, and not stumble on the stone God has set in place (Isa. 8:14; 28:13, 16).

Here is the mystery of the Kingdom. It has come in power, for Christ has come; where the King is, there the Kingdom is manifested. When he stands among men, then the Kingdom is among them (Luke 17:21). But his manifestation of the Kingdom is in mercy, not wrath; grace, not judgment. Is this a scandal, an offense, that Christ should preach release to the captive while John remains in prison awaiting beheading at Herod’s whim? No, because Christ has come first not to smite but to be smitten, not to execute wrath but to endure it. To John as to the apostles is given the privilege of fellowship in Christ’s sufferings together with the promise of joy in his Kingdom.

Christ as the One who was to come actualizes the Kingdom, reveals its true nature, and establishes its program. The Old Testament prepares for all these functions as it predicts the sufferings of Christ and the glories that should follow (Luke 24:26, 27; Acts 17:23).

No Zealot captain could fulfill the kingdom promises of the Old Testament. Much more than a Maccabean kingdom is foretold by the prophets. The ideal of a kingdom at peace had been realized at Solomon’s dedication of the temple, but in the centuries of sin and judgment that followed a greater triumph of God’s salvation had been predicted. From destruction and exile God would not only preserve a remnant but also renew the people of God; the dead bones in the valley must live and be given the Spirit of God, with hearts of flesh, not stone. The nations, used as instruments of judgment upon Israel, will themselves be judged and come to share in the glories of the people of God.

So great are the promised mercies that only God himself can bring them: he must come to gather the scattered flock (Ezek. 34:12; Isa. 40:10, 11). Yet not only will the Lord come; the Servant will also come. The Messiah is promised both as Lord, bearing the Divine Name (Isa. 9:6), and as Servant, bearing the name of Israel (Isa. 42:1; 43:1). The motif of suffering and renewal will come to fulfillment in the personal Servant of the Lord who bears the sin of many and is given for a covenant of the people and a light of the Gentiles (Isa. 42:6).

From his birth in a stable to his death on the cross, Christ actualizes the kingdom promises in suffering; from his resurrection to the day of his appearing he actualizes the same Kingdom in glory.

The mystery that staggered John the Baptist is woven throughout the whole revelation of the Kingdom and the King. Angels announce the birth of the Messiah, but they come to shepherds and send them to seek a cattle manger. Wise men from the Gentiles bring the wealth of nations in tribute to the king of the Jews, but only divine intervention prevents their worship from marking Christ for the sword of Herod. In Egypt, God’s Son is preserved again, but the Innocents are slaughtered in Bethlehem.

Christ’s ministry begins the gathering process; his disciples help him as “fishers of men” (Matt. 4:19). He calls the lost sheep of the house of Israel and promises to the “little flock,” the remnant of the last days, the Father’s gift of the Kingdom (Luke 12:32). But the Kingdom Christ describes is shaped in the pattern of his own ministry as the Suffering Servant. When the disciples ask about sharing his throne of glory, he asks about sharing his cup of suffering (Matt. 20:22).

He comes as Lord, but he imposes his yoke as the one who is meek and lowly of heart (Matt. 11:29). He does not strive or cry aloud, and he teaches his disciples to turn the other cheek in the ministry of suffering. He came to minister, and his disciples are not to rule like princes of the Gentiles but to serve as their humble Lord does (Matt. 20:25–28).

Power he has: over the wind and the sea, sickness and death, demons and Satan. His disciples too are given authority over the hosts of darkness, but they are sent as sheep in the midst of wolves (Matt. 10:19)—the one act of judgment they may perform against a town that will not receive them is to shake the dust off their feet in silent witness to God (Matt. 10:14).

One great truth brings harmony to the contrasting elements in the revelation of the Kingdom; it is this: the Kingdom of the Saviour is the Kingdom of God. Because the Kingdom is of God and not of Israel, of heaven and not of earth, the who, the how, and the when of the Kingdom are divine. Since the Kingdom centers on God, it is not an impersonal structure of power but the presence of God in power. The Kingdom is Christ. God’s righteousness, not man’s, is the requirement of the Kingdom, and God’s righteousness in Christ is the gift of the Kingdom. The sons of the Kingdom are Christ’s little flock, those gathered with him to the kingdom feast (Luke 12:32; 13:25, 26). They are born from above, born of the Spirit (John 3:5).

The how of the Kingdom is of God, too. Not man’s strength but God’s, not man’s wisdom but God’s, brings the kingdom in. To this lesson the whole Old Testament moves—“not by might, nor by power, but by my Spirit, saith the Lord of hosts” (Zech. 4:6). God’s ways are not man’s ways; the way of the Kingdom is the way of the King who comes, meek and lowly, to die. Not all the political power on earth can bring in God’s Kingdom. Not twelve legions of angels, not even sheer omnipotence, can do it. Only the personal, living God of grace can do it, in his own way.

The when of the Kingdom is part of the how. God’s salvation is programmed. Christ’s ministry moves from sufferings to glory, from earth to heaven. John the Baptist could not understand the delay of judgment. But for God, justice delayed is not justice denied. Because Christ comes to bear the judgment, the delay reveals God’s long-suffering grace. The feast is ready but the house is not full; it is grace that holds open the doors while the Servant gathers from the highways and hedges the poor, the maimed, the halt, and the blind (Luke 14:15–24). Yet when judgment comes, it will be no less divine. The Son of Man will come again in the glory of the Father, with the holy angels (Matt. 10:15; 16:27; 21:33–46; 24:3, 30, 42), and all men will appear before the judgment seat of Christ (2 Cor. 5:10). The harvest is delayed for the sake of the wheat, but the tares will be burned in fire (Matt. 13:30, 42). The suffering sons of the Kingdom are not to judge but to leave judgment to God (Matt. 7:1). In “the Day,” the Judge of all the earth will do right (2 Tim. 4:1; Gen. 18:25).

PRAYER FOR A HEARTS SPRING

O see how wild the west wind blows my love

to numbness in the cold, bold blast of Spring

And feeling ceases, clutching in the dark

for remnants of an old, worn tattered thing.

For faith is drowned so soon in sparkling wines

and piety in every singing bed

and gaunt grace haunts the empty temple halls

and mocking guilt sits lightly on her head.

Ah, Christ! how dead Thy hurts in this my heart!

Though each red blunt-tipped nail does rip and tear

and all Thy wounds run wormwood, gall, and yet

no fiery paraclete my soul does sear.

O grip my heart, Iron Clasper, wring it out!

Unravel Thou this anaesthetic night;

slice, jagged down the temple tapestries

and pain me, dazzle, stab with blades of Light!

JOANNE RHUDY HARRISON

To resist God’s plan for his kingdom is to declare for Satan in the spiritual warfare of the ages. When Simon Peter draws the sword in Gethsemane to defend Christ, he is minding the things of men, not the things of God (Matt. 26:52; 16:23). The blow at the head of Malchus is a blow against the kingdom will of God. Satan had promised Christ all the kingdoms of the world if he would receive them by obedience to him rather than by obedience to the Father’s will. Satan offered the way of power: stones into bread, flight-testing the Messianic call, joining the rebellion by signing up with Satan (Matt. 4:1–11). Jesus renounced the worldly form of the kingdom in the wilderness, at Caesarea Philippi, in Gethsemane, on Calvary. He took his cross instead and commanded every disciple to do the same. To seek to bring in the Kingdom by the use of worldly power is to deny the cross of the King and the heavenliness of the Kingdom. The choice is not between individual salvation and social salvation; it is between the revealed will of God and the presumption of man.

It is often assumed that because evangelicals do not advocate a social gospel, they do not have a Gospel for society but only for individuals. Not so. The Kingdom of heaven gathers men and appears among them. But it does so as the Kingdom of heaven, not as a kingdom of this world. Jesus told the unbelieving leaders of the theocratic nation that the Kingdom of God would be taken away from them and given to another nation that would bring forth the fruits of the Kingdom (Matt. 21:43). This other “nation” is not a kingdom with political boundaries and a standing army. It is rather the new form of the people of God brought about by the principles of the Kingdom, a form that is social—joining men as disciples of the King, the flock of the Shepherd—but that is precisely not political, not a kingdom of this world.

Christ himself gave the new form to the Kingdom when he established the New Testament Church (Matt. 16:18, 19). Like the assembly of Israel at Sinai and the feast-day assemblies at Jerusalem, the Church is the assembly of the people of God, those brought together by the call of God to stand in his presence.

To the confessing Peter, the spokesman for the apostles (Matt. 16:18, 19), and to all the apostles (Matt. 18:18), Christ gives the keys of the Kingdom, with authority to bind and loose in his name. This kingdom authority has heavenly sanction: it will be worse, in the day of judgment, for those who reject the word of the apostles than for Sodom and Gomorrah (Matt. 10:15). Yet the authority is limited to Christ’s Word and Christ’s name. It is a declaration of two or three witnesses assembled in Christ’s name, who invoke Christ’s presence (Matt. 18:18–20). Of course, not every word spoken in Christ’s name will be acknowledged in the day of judgment (Matt. 7:22, 23). But the spiritual discipline of the Word of Christ, faithfully exercised, expresses on earth in urgent warning the very verdict of heaven.

Yet it does not execute this verdict. The extreme of discipline in the new form of the people of God is to declare a man to be as a Gentile and a publican. This stands in strong contrast to the “cutting off” of an apostate member of the Old Testament congregation by stoning. The reason for the difference, surprisingly, is not a weakening but a strengthening of the theocratic motif. Before the King and Judge came, the reality of the judgment was physically anticipated. When Christ came, however, both the reality of the day of judgment and the delay of the day of judgment were revealed. The actuality, the realism, of the Kingdom put all judgment directly into the hands of God. Christ is not made a judge or divider under the temporal regime of the old theocracy (Luke 12:14), because the Father has directly committed all judgment into the hands of Christ as his Son (John 5:26, 27). The Son now has all authority in heaven and earth and uses that authority to fulfill the Father’s will for the Kingdom. Christ may smite a blaspheming Herod (Acts 12:23) or bring temporal chastisement on his Church (1 Cor. 11:30), but he gives to no man the sword of his lips.

Paul declares that the weapons of his warfare are not temporal but spiritual (2 Cor. 10:4). To the man who knows the Kingdom, this is not weakness but strength. It means that the battle is joined against the citadel of the real enemy, the spiritual powers of darkness.

Christ rules the world before the day of judgment, but he does not give that rule to his disciples on earth. He has appointed that those who suffer with him now will one day reign with him. The saints will judge even the angels in the future, but they judge only themselves now (1 Cor. 5:12; 6:1–3). They are not called to rule or judge any but those who name Christ’s name. When Christ comes again, the Church triumphant, not the Church militant, will judge the world.

The apparent tensions of what the New Testament says about the state can be resolved by understanding what is taught about the Kingdom and the Church.

The state cannot now be a direct expression of the Kingdom, because the program of the Kingdom withholds the sword of judgment. The only judgment that can be pronounced in Christ’s name is spiritual.

What then about the structures of worldly power? Are they the forms of Satan’s kingdom in opposition to the Kingdom of Christ?

No, such a conclusion would not agree with what the Bible teaches about the Kingdom of God. The Old Testament theology of the dispersed remnant among the nations does contrast the Kingdom of God with the idolatrous kingdoms of men (Dan. 2:44). Yet it also shows God’s continuing rule over all kings and kingdoms (Dan. 6:26) and the blessings that are given to and through these power structures of men. The saints become a light and a salt to strengthen wise administration and justice in heathen empires. Heathen kings, in turn, are used to make provisions for justice in which the people of God may prosper and be restored (Isa. 45:1, 13).

The coming of God’s Kingdom in Christ makes specific God’s rule over the nations. Jesus Christ is King of kings and Lord of lords. His authority as the ascended King is over every earthly kingdom.

His rule over the nations, however, is not the same as his rule over the Church. All things are put in subjection to him; he is the head over all things for his Church, which is his body (Eph. 1:22, 23). Only the Church is the body of Christ. (The figure of headship as Paul uses it is independent of the body figure.) The corporate description of growth into one new man in Christ (Eph. 4:12–16) can apply only to the Church. It takes place through the gifts of ministry given by Christ to his Church.

Those who rule in the state may be called “ministers of God” (Rom. 13:4), for their rule is within the appointment of God in his ordaining of human government. Christ’s exalted rule subjects these “ministers of God” to him. They serve the purpose of Christ in maintaining a world where judgment is deferred. But while their rule is subjected to Christ’s control, it is not exercised in Christ’s name. The structure of the state is not part of the new order to come.

Christ therefore could command rendering to Caesar that which was Caesar’s as well as to God that which is God’s. Of course, all things are God’s; but Christ’s answer is not ironical. The power given to Pilate or Caesar is from above (John 19:11). Until Christ comes again it will continue to be exercised. Christ’s authority over all rule does not guarantee freedom from persecution to the Church. The Church is called to suffer, and the state does forsake its divinely appointed function and become a threat to the good rather than to the evil. The state is nevertheless to be obeyed unless its commands require disobedience to the revealed will of God.

The Christian understanding of the state only makes sense after a Christian understanding of the Kingdom and the Church. If the how and the when of the Kingdom are forgotten, another view of the state will arise—to the loss of Christian liberty. Men who do not look for the second coming of Christ will not understand the patience and meekness of the present kingdom. Even if they think of themselves as servants of Christ, they will try to make him king by force. But Christ’s Kingdom is not of this world, and his officers cannot fight to bring it in (John 18:36). Christ’s Kingdom is present as Christ is present, in the gifts of the Holy Spirit; Christ’s Kingdom will come as Christ will come, in power and glory. Life in the state—indeed, in all the world—is permeated by the leaven of the Kingdom; but no political ruler has the right to raise the banner of Christ’s name over his armies. Neither has the Church the right to reorganize itself in the secular pattern of this-wordly power. The Church cannot redeem society by political action; when evangelism becomes politics, it is no longer the Gospel of Christ’s Kingdom.