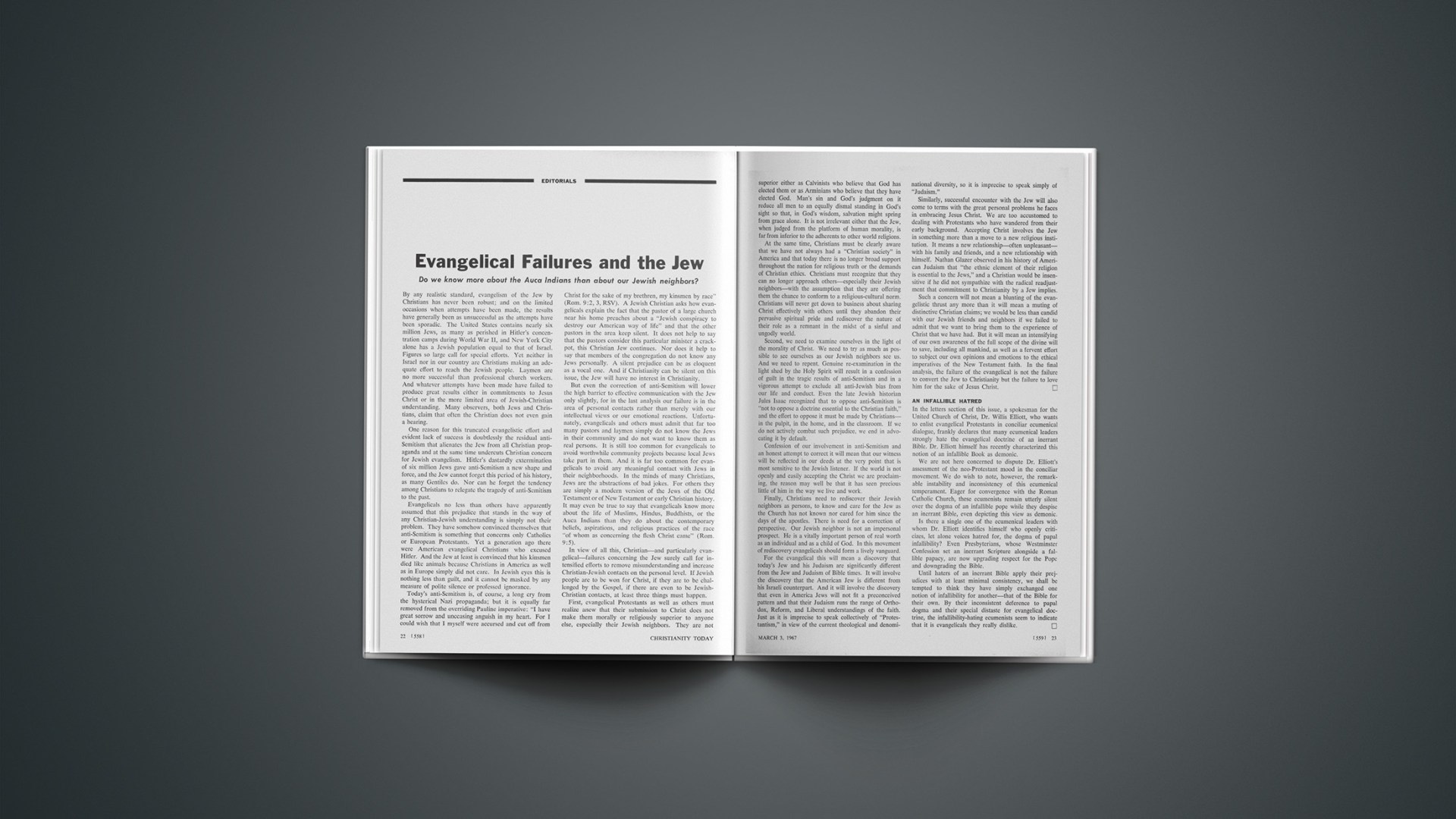

Do we know more about the Auca Indians than about our Jewish neighbors?

By any realistic standard, evangelism of the Jew by Christians has never been robust; and on the limited occasions when attempts have been made, the results have generally been as unsuccessful as the attempts have been sporadic. The United States contains nearly six million Jews, as many as perished in Hitler’s concentration camps during World War II, and New York City alone has a Jewish population equal to that of Israel. Figures so large call for special efforts. Yet neither in Israel nor in our country are Christians making an adequate effort to reach the Jewish people. Laymen are no more successful than professional church workers. And whatever attempts have been made have failed to produce great results either in commitments to Jesus Christ or in the more limited area of Jewish-Christian understanding. Many observers, both Jews and Christians, claim that often the Christian does not even gain a hearing.

One reason for this truncated evangelistic effort and evident lack of success is doubtlessly the residual anti-Semitism that alienates the Jew from all Christian propaganda and at the same time undercuts Christian concern for Jewish evangelism. Hitler’s dastardly extermination of six million Jews gave anti-Semitism a new shape and force, and the Jew cannot forget this period of his history, as many Gentiles do. Nor can he forget the tendency among Christians to relegate the tragedy of anti-Semitism to the past.

Evangelicals no less than others have apparently assumed that this prejudice that stands in the way of any Christian-Jewish understanding is simply not their problem. They have somehow convinced themselves that anti-Semitism is something that concerns only Catholics or European Protestants. Yet a generation ago there were American evangelical Christians who excused Hitler. And the Jew at least is convinced that his kinsmen died like animals because Christians in America as well as in Europe simply did not care. In Jewish eyes this is nothing less than guilt, and it cannot be masked by any measure of polite silence or professed ignorance.

Today’s anti-Semitism is, of course, a long cry from the hysterical Nazi propaganda; but it is equally far removed from the overriding Pauline imperative: “I have great sorrow and unceasing anguish in my heart. For I could wish that I myself were accursed and cut off from Christ for the sake of my brethren, my kinsmen by race” (Rom. 9:2, 3, RSV). A Jewish Christian asks how evangelicals explain the fact that the pastor of a large church near his home preaches about a “Jewish conspiracy to destroy our American way of life” and that the other pastors in the area keep silent. It does not help to say that the pastors consider this particular minister a crackpot, this Christian Jew continues. Nor does it help to say that members of the congregation do not know any Jews personally. A silent prejudice can be as eloquent as a vocal one. And if Christianity can be silent on this issue, the Jew will have no interest in Christianity.

But even the correction of anti-Semitism will lower the high barrier to effective communication with the Jew only slightly, for in the last analysis our failure is in the area of personal contacts rather than merely with our intellectual views or our emotional reactions. Unfortunately, evangelicals and others must admit that far too many pastors and laymen simply do not know the Jews in their community and do not want to know them as real persons. It is still too common for evangelicals to avoid worthwhile community projects because local Jews take part in them. And it is far too common for evangelicals to avoid any meaningful contact with Jews in their neighborhoods. In the minds of many Christians, Jews are the abstractions of bad jokes. For others they are simply a modern version of the Jews of the Old Testament or of New Testament or early Christian history. It may even be true to say that evangelicals know more about the life of Muslims, Hindus, Buddhists, or the Auca Indians than they do about the contemporary beliefs, aspirations, and religious practices of the race “of whom as concerning the flesh Christ came” (Rom. 9:5).

In view of all this, Christian—and particularly evangelical—failures concerning the Jew surely call for intensified efforts to remove misunderstanding and increase Christian-Jewish contacts on the personal level. If Jewish people are to be won for Christ, if they are to be challenged by the Gospel, if there are even to be Jewish-Christian contacts, at least three things must happen.

First, evangelical Protestants as well as others must realize anew that their submission to Christ does not make them morally or religiously superior to anyone else, especially their Jewish neighbors. They are not superior either as Calvinists who believe that God has elected them or as Arminians who believe that they have elected God. Man’s sin and God’s judgment on it reduce all men to an equally dismal standing in God’s sight so that, in God’s wisdom, salvation might spring from grace alone. It is not irrelevant either that the Jew, when judged from the platform of human morality, is far from inferior to the adherents to other world religions.

At the same time, Christians must be clearly aware that we have not always had a “Christian society” in America and that today there is no longer broad support throughout the nation for religious truth or the demands of Christian ethics. Christians must recognize that they can no longer approach others—especially their Jewish neighbors—with the assumption that they are offering them the chance to conform to a religious-cultural norm. Christians will never get down to business about sharing Christ effectively with others until they abandon their pervasive spiritual pride and rediscover the nature of their role as a remnant in the midst of a sinful and ungodly world.

Second, we need to examine ourselves in the light of the morality of Christ. We need to try as much as possible to see ourselves as our Jewish neighbors see us. And we need to repent. Genuine re-examination in the light shed by the Holy Spirit will result in a confession of guilt in the tragic results of anti-Semitism and in a vigorous attempt to exclude all anti-Jewish bias from our life and conduct. Even the late Jewish historian Jules Isaac recognized that to oppose anti-Semitism is “not to oppose a doctrine essential to the Christian faith,” and the effort to oppose it must be made by Christians—in the pulpit, in the home, and in the classroom. If we do not actively combat such prejudice, we end in advocating it by default.

Confession of our involvement in anti-Semitism and an honest attempt to correct it will mean that our witness will be reflected in our deeds at the very point that is most sensitive to the Jewish listener. If the world is not openly and easily accepting the Christ we are proclaiming, the reason may well be that it has seen precious little of him in the way we live and work.

Finally, Christians need to rediscover their Jewish neighbors as persons, to know and care for the Jew as the Church has not known nor cared for him since the days of the apostles. There is need for a correction of perspective. Our Jewish neighbor is not an impersonal prospect. He is a vitally important person of real worth as an individual and as a child of God. In this movement of rediscovery evangelicals should form a lively vanguard.

For the evangelical this will mean a discovery that today’s Jew and his Judaism are significantly different from the Jew and Judaism of Bible times. It will involve the discovery that the American Jew is different from his Israeli counterpart. And it will involve the discovery that even in America Jews will not fit a preconceived pattern and that their Judaism runs the range of Orthodox, Reform, and Liberal understandings of the faith. Just as it is imprecise to speak collectively of “Protestantism,” in view of the current theological and denominational diversity, so it is imprecise to speak simply of “Judaism.”

Similarly, successful encounter with the Jew will also come to terms with the great personal problems he faces in embracing Jesus Christ. We are too accustomed to dealing with Protestants who have wandered from their early background. Accepting Christ involves the Jew in something more than a move to a new religious institution. It means a new relationship—often unpleasant—with his family and friends, and a new relationship with himself. Nathan Glazer observed in his history of American Judaism that “the ethnic element of their religion is essential to the Jews,” and a Christian would be insensitive if he did not sympathize with the radical readjustment that commitment to Christianity by a Jew implies.

Such a concern will not mean a blunting of the evangelistic thrust any more than it will mean a muting of distinctive Christian claims; we would be less than candid with our Jewish friends and neighbors if we failed to admit that we want to bring them to the experience of Christ that we have had. But it will mean an intensifying of our own awareness of the full scope of the divine will to save, including all mankind, as well as a fervent effort to subject our own opinions and emotions to the ethical imperatives of the New Testament faith. In the final analysis, the failure of the evangelical is not the failure to convert the Jew to Christianity but the failure to love him for the sake of Jesus Christ.

An Infallible Hatred

In the letters section of this issue, a spokesman for the United Church of Christ, Dr. Willis Elliott, who wants to enlist evangelical Protestants in conciliar ecumenical dialogue, frankly declares that many ecumenical leaders strongly hate the evangelical doctrine of an inerrant Bible. Dr. Elliott himself has recently characterized this notion of an infallible Book as demonic.

We are not here concerned to dispute Dr. Elliott’s assessment of the neo-Protestant mood in the conciliar movement. We do wish to note, however, the remarkable instability and inconsistency of this ecumenical temperament. Eager for convergence with the Roman Catholic Church, these ecumenists remain utterly silent over the dogma of an infallible pope while they despise an inerrant Bible, even depicting this view as demonic.

Is there a single one of the ecumenical leaders with whom Dr. Elliott identifies himself who openly criticizes, let alone voices hatred for, the dogma of papal infallibility? Even Presbyterians, whose Westminster Confession set an inerrant Scripture alongside a fallible papacy, are now upgrading respect for the Pope and downgrading the Bible.

Until haters of an inerrant Bible apply their prejudices with at least minimal consistency, we shall be tempted to think they have simply exchanged one notion of infallibility for another—that of the Bible for their own. By their inconsistent deference to papal dogma and their special distaste for evangelical doctrine, the infallibility-hating ecumenists seem to indicate that it is evangelicals they really dislike.

Canadian Church On Divorce

The United Church of Canada, supported by some other religious groups, has submitted a ninety-three-page brief to Canada’s Senate–Commons Committee on Divorce. It calls for “church and government [to] act together” and recommends that divorces be granted for “marriage breakdown” after three years of separation and unsuccessful compulsory efforts at reconciliation.

We venture a few comments. By calling upon the state to change its divorce regulation, the church is acting politically, and this is not its function. Nor has it any right to water down biblical standards for believers by advocating that “marriage breakdown” be made grounds for divorce. While it ought not to impose its own higher ethic of marriage on unbelievers, the church does have the sacred duty of speaking with authority to its own members about marriage and its indissolubility.

The state has an interest in marriage as a legal contract and a moral force. The church’s concern for community morals, however, should be expressed, not through the use of legislative coercion, but through the proclamation and application of biblical norms in the lives of churchgoers, which is the best way to call attention to its views.

The Revolution In Morality

A common practice in the theological arena is to try to create sympathy for one’s own novelties by caricaturing other views. For two generations those to the left of evangelical theology—modernist, dialectical, and existentialist spokesmen alike—have deplored as rationalistic, legalistic, and fundamentalistic whatever collided with their own free-wheeling preferences. Between the ugly inherited tradition and the most radical contemporary option conceivable there remained little choice, except the splendid mediating position of the reconstructionist of the moment.

More recently this “straw man” tactic has been applied to evangelical statements of Christian ethics. George Forell, head of the School of Religion at the State University of Iowa, declares that the “biblicistic” approach of works like Christian Personal Ethics (by the editor of CHRISTIANITY TODAY) is “largely responsible” for the current moral revolution with its acceptance of Fletcher’s situationalism. In a plenary paper delivered in Chicago at the Sixth University Staff Assembly of the Lutheran Academy for Scholarship, Forell scored contemporary philosophical ethics (as represented by logical positivism, Marxism, and existentialism), the ontological, “natural law” ethic of Roman Catholicism (even Teilhard de Chardin “did not take sin seriously”), Barth’s ethic (viewed by Forell as a Christocentric, “Second Person” reductionism), and the Fletcher–Lehmann situational ethic. Then he deplored what he claimed was the underlying assumption of evangelical works like Christian Personal Ethics, that “for any ethical problem there is a scriptural passage which will supply the answer”—the manifestation of a “biblicism” that allegedly drives modern man into the arms of the situationists. As a corrective to all these positions, Forell offered a “trinitarian ethic” stressing the dynamic resources of God as the Father who orders human life, the Son who redeems it, and the Spirit who sanctifies it.

John Warwick Montgomery, chairman of the Division of Church History and History of Christian Thought at Trinity Evangelical Divinity School, supplied an evangelical rejoinder. While concurring with Forell’s criticisms of naturalistic, Roman Catholic, Barthian, and situational ethics, Montgomery emphasized that the evangelical position stated in Christian Personal Ethics contends, over against pharisaic legalism, that “the New Testament does not give a rule to cover every possibility in life.” He assessed Forell as “a poorer Lutheran than Baptist Henry,” since Lutherans insist that the total ethical teaching of a divinely inspired Scripture is permanently binding for mankind, not merely reflective of the social milieu of the ancient Near East. Forell’s “trinitarian ethic,” on the other hand, is as reductionistic in principle as the “agapeistic” ethic of the situationists, and far less justifiable apart from a fully authoritative biblical revelation. “Why,” Montgomery asked Forell, “should anyone consider the trinitarian teaching of the Bible to be supra-cultural and normative if the Ten Commandments, the Sermon on the Mount, the Pauline teaching on sanctification, and so on, can be viewed as culturally conditioned and therefore non-absolute?”

Educational Integrity And The C.I.A.

A storm has gathered in Washington in the aftermath of the disclosure of secret CIA funding of college student organizations for ideological objectives, and President Johnson has moved to protect the “integrity and independence” of the nation’s educational community. The loudest cries of protest come from those who, on policy, tend easily to identify themselves with left-wing views on Viet Nam, have little use for the CIA, and seek to discredit the House Un-American Activities Committee.

We do not think that the CIA, or any other government agency, is above criticism. Nor are we happy about the use of government funds on campuses to promote specific ideological goals. But infiltration of national and international student life by professional Communists is at least equally deplorable. And the attempt to resist Communist subversion in this way may have been demanded by the circumstances. Responsible criticism of the agency’s methods should suggest other means of attaining legitimate CIA goals.

The most important aspect of the issue of integrity in American education, however, runs deeper than the CIA controversy. Most American campuses are presently indebted to the government for funds and will be so increasingly in the years ahead. “We shall require huge sums of money, from both public and private sources, for higher education in this country,” said Harvard President Nathan M. Pusey recently. The sooner the nation’s educators learn that government money involves not simply government aid but ultimately, perhaps, government control in one form or another, the sooner the question of the integrity and independence of education will be faced in depth.