“We are faced with a rising number of responsive populations. Enough of these exist to absorb all the missionary resources of the Church and still require more.”

The rise of receptive populations is a great new fact in missions. There have always been populations in which many are willing to hear the Gospel and become responsible members of Christ’s Church. But today their number in all the continents has risen so sharply that they have become an outstanding feature of the mission landscape.

Mankind is not one vast, homogeneous mass; it is made up of many societies, classes, castes, and tribes. Each receives or resists the Gospel in its own time and in its own way. If we are to see humanity correctly, we must see it as a great mosaic, each piece of which, though it is in contact with others, has its own color and texture. That many pieces are today responsive is of paramount importance to the Church as it engages in mission.

To be sure, there are still many resistant and rebellious populations with faces set like flint against the Saviour. Generations of missionaries have spent their lives among them, proclaiming the Lord of love, beseeching men to be reconciled to him, and portraying him by loving service in hospitals and schools. Yet though these groups continue to reject Christ, this fact must not hide from our view the rising number of responsive populations. Enough of these exist to absorb all the missionary resources of the Church and still require more.

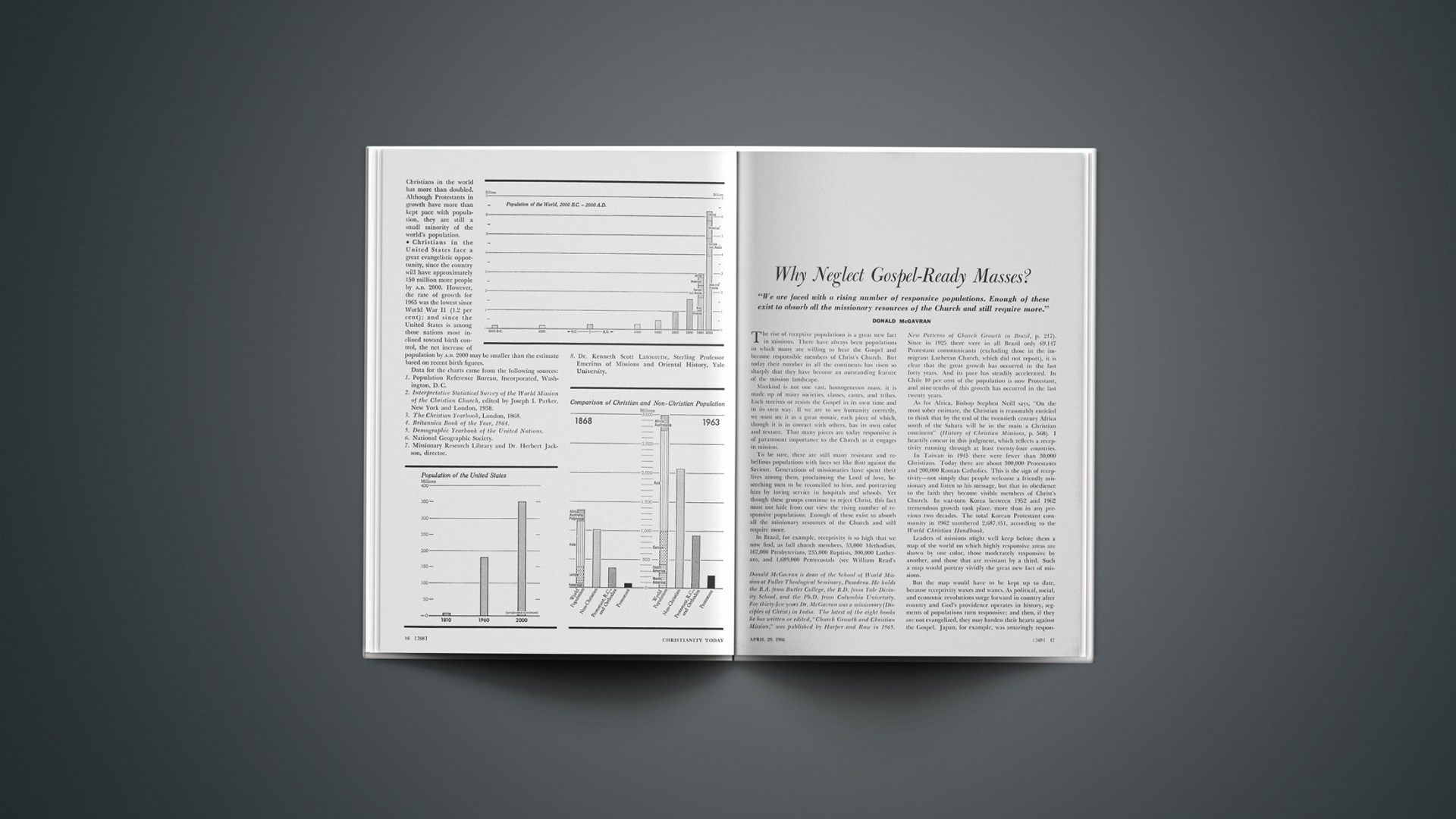

In Brazil, for example, receptivity is so high that we now find, as full church members, 53,000 Methodists, 167,000 Presbyterians, 235,000 Baptists, 300,000 Lutherans, and 1,689,000 Pentecostals (see William Read’s New Patterns of Church Growth in Brazil, p. 217). Since in 1925 there were in all Brazil only 69,147 Protestant communicants (excluding those in the immigrant Lutheran Church, which did not report), it is clear that the great growth has occurred in the last forty years. And its pace has steadily accelerated. In Chile 10 per cent of the population is now Protestant, and nine-tenths of this growth has occurred in the last twenty years.

As for Africa, Bishop Stephen Neill says, “On the most sober estimate, the Christian is reasonably entitled to think that by the end of the twentieth century Africa south of the Sahara will be in the main a Christian continent” (History of Christian Missions, p. 568). I heartily concur in this judgment, which reflects a receptivity running through at least twenty-four countries.

In Taiwan in 1945 there were fewer than 30,000 Christians. Today there are about 300,000 Protestants and 200,000 Roman Catholics. This is the sign of receptivity—not simply that people welcome a friendly missionary and listen to his message, but that in obedience to the faith they become visible members of Christ’s Church. In war-torn Korea between 1952 and 1962 tremendous growth took place, more than in any previous two decades. The total Korean Protestant community in 1962 numbered 2,687,451, according to the World Christian Handbook.

Leaders of missions might well keep before them a map of the world on which highly responsive areas are shown by one color, those moderately responsive by another, and those that are resistant by a third. Such a map would portray vividly the great new fact of missions.

But the map would have to be kept up to date, because receptivity waxes and wanes. As political, social, and economic revolutions surge forward in country after country and God’s providence operates in history, segments of populations turn responsive; and then, if they are not evangelized, they may harden their hearts against the Gospel. Japan, for example, was amazingly responsive between 1946 and 1953, but after that her receptivity declined.

Much receptivity passes away without commensurate church planting. Most missions are geared to the long, hard pull, and when sudden receptivity appears, they do not change fast enough to reap the harvest. Few missionaries dedicated to great church planting went to Japan immediately after World War II. Some solid missions in Latin America are achieving little church growth, because their resources are committed to activities fitted for 1945, not 1965. In Taiwan, the whole Highlander population (perhaps 220,000) could have been Presbyterian; but in 1956 (ten years after its striking new receptivity became abundantly apparent) there were only six Presbyterian missionary families assigned to this huge receptive population. And so today there are only 80,000 Highlander Presbyterians.

The great new fact of receptivity demands theological understanding. Receptivity does not arise by accident. Men become open to the Gospel, not by any blind interplay of brute forces, but by God’s sovereign will. Over every welcoming of the Gospel, we can write, “In the fullness of time God called this people out.”

This being so, it follows that as the Church leads men to the Promised Land, Gospel-accepters have a higher priority than Gospel-rejecters. Paul always observed this theological principle. At Antioch of Pisidia he said to the resistant Jews, “… Since you thrust it [the Gospel] from you, and judge yourselves unworthy of eternal life, behold, we turn to the Gentiles. For so the Lord has commanded us …” (Acts 13:46, 47, RSV). This principle guided the early Church in its expansion.

It pleases God for the missionary enterprise to determine its main thrusts in light of the growth of the Church. The bold acceptance of church growth as the goal of Christian mission is a theological decision, the bedrock on which correct action in the face of receptivity rests.

Together with an understanding of the theological meaning of receptivity there must go both an acceptance of the Bible as the true, authoritative revelation of God and a living experience of Christ. Certainty and fervency are the ground of church growth. If the responsive peoples of the world are to receive Christ, the messengers of God must let the Holy Spirit have his way in their lives and must believe that God has revealed his will perfectly and finally in the Bible.

The principles of church growth operate through the power of Christ and his Word and can be used effectively only by ardent, Spirit-filled Christians. We evangelize the nations not for self-aggrandizement but in obedience to our Master’s command. Among receptive peoples, growth is a test of the Church’s faithfulness.

Today’s receptivity also demands response on the part of the Church. Correct theological understanding of receptivity must be implemented by action guided by church-growth principles. Among many of these, six can be mentioned.

The first is to increase evangelism everywhere, and especially among growing churches. It is a commonplace in the world of missions that growing churches should be strongly reinforced and static churches lightly assisted. Reinforcement must issue in greatly expanded convert-winning, church-planting evangelism. When God grants his Church a precious growing point, let her make sure that it continues to grow. The first thing is not rich material or educational assistance. That will come later. If growth is great, material assistance can be used profitably; if growth ceases or remains small, much material assistance may prove fatal.

The initial principle of the church’s outreach is to harvest the crop, to put in the sickle. Nothing takes the place of action. In the presence of receptivity, the one thing to do is to bring in the sheaves.

The second principle of church growth is to multiply unpaid leaders among the new converts, training them to go out and communicate Christ to their unsaved relatives, neighbors, and fellow laborers. Any form of clericalism, any limiting of evangelism to paid leaders, works heavily against church growth. In a receptive situation, growth occurs in the church that mobilizes its laymen for continuous propagation of the Good News. Conversely, even in a highly receptive population, a church in which evangelism is an activity chiefly of missionaries or paid nationals does not grow.

There are many plans for training unpaid leaders. A good plan ought to integrate the individual into an organized churchwide effort. Mere organization, however, will accomplish little. The real measure of a good plan is that it mediates a deepened experience of Christ, and gets ordinary Christians gladly bearing witness to what Christ has done for them and persuading their fellows to become disciples of Christ.

The third principle is to take full advantage of insights now available from the sciences concerned with man. In receptive populations in Asia, Africa, and Latin America, we should apply the knowledge of anthropology, sociology, and psychology to the task of reaching all men with the Gospel. An army of scientists are discovering detailed information about the social structures of classes, tribes, and castes everywhere, and the processes by which it pleases Almighty God to change societies are becoming known. Servants of Christ have the privilege of using the now known dynamics of culture-change to mediate Christ to men. Missionaries regard these insights from the social sciences as particularly important in the propagation of the Gospel.

The fourth principle of church growth is to evangelize responsive populations to the utmost. Too often a responsive field is regarded as a dangerous competitor of resistant fields and aided only slightly. Those who follow this fourth principle, however, will, on hearing of a responsive field, determine by scientific survey how responsive it is, and then make up and send in a task force to evangelize the population to its limits. Missionaries should not be sent to “work among” a receptive population. That phrase is a device of Satan! Missionaries should be sent to multiply churches and yet more churches in every receptive population on earth. And those sent should be trained in how to multiply churches in that kind of responsive population.

A weighty consideration is that as receptive peoples become Christian, they will in turn reach presently resistant peoples who may be rejecting centuries of European aggression rather than the Christian faith. One result of pouring resources into Africa south of the Sahara may well be that, once there are millions of Christians there, they will establish missions in the Muslin north and do a much more effective work there than Europeans, handicapped by the inheritance of the Crusades, have been able to do.

The fifth principle is to seek, without lessening emphasis on individual salvation, the joint accession of many persons within one society at one time. Not all members of a given social unit will accept the Saviour; but the more that become his disciples at one time, the better. Normal man is man-in-society. Wherever a man can become a Christian only by renouncing his own people, the Gospel spreads slowly and churches remain weak. Wherever men follow the New Testament pattern and side by side become Christians, there the Gospel spreads rapidly and churches develop muscle. Christian missions should learn all they can about normal group movements to Christ and help persons come to Christ with their families and relatives.

The sixth principle of harvest is to carry on extensive research in church growth. Astonishing discoveries about the growth of churches lie hidden in denominational, regional, and linguistic pockets. The facts about church growth must be laid out for all to see. To discover what churches are growing, to determine principles of their growth, and to apply these principles to non-growing churches—this is a basic requisite for church growth.

The secular world pours millions of dollars into research, considering it essential to progress in today’s changing world. It is high time for the Church to channel 5 per cent of what it spends for missions into research in church growth. Until this is done, missions will not see or develop the full potential for growth at which the finger of God now points.

Once research uncovers methods God is blessing in various communions, the new era of good feeling among the churches should issue in willingness to use these methods. If the Anglicans and Friends are growing in Kenya, other churches in Africa ought to find out and adopt the procedures that have led to this success in bringing men to God through Jesus Christ.

As these six principles and others governing action for growth are learned by the churches and applied to the responsive populations now emerging on every continent, the Church will enter a new era of obedience. She will liberate population after population by introducing them to the abundant life in Christ. She will bring them to advances in health, productivity, and education. And once more she will be shown the truth of the Lord’s saying, “Seek first his kingdom and his righteousness, and all these things shall be yours as well.”