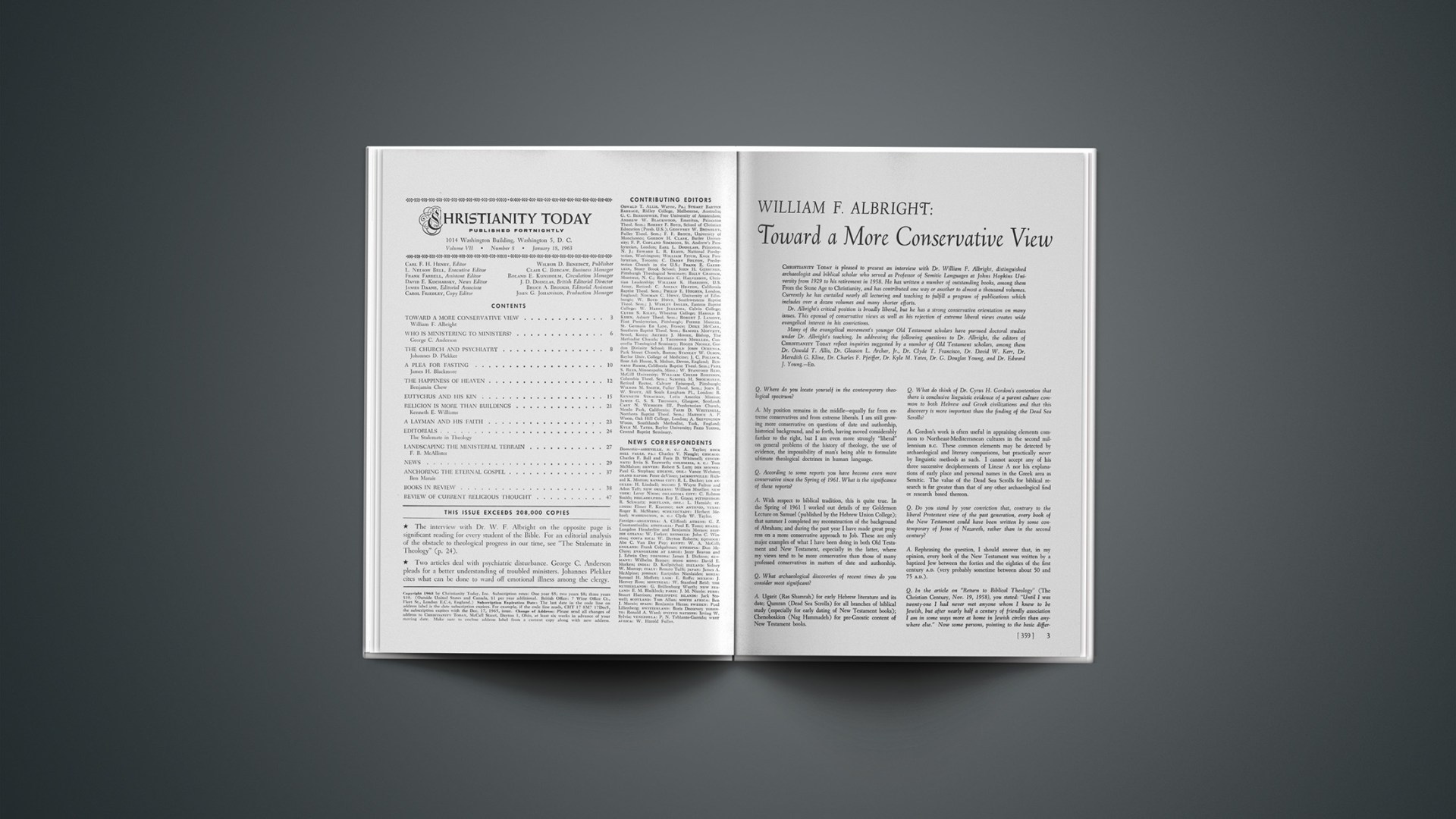

CHRISTIANITY TODAYis pleased to present an interview with Dr. William F. Albright, distinguished archaeologist and biblical scholar who served as Professor of Semitic Languages at Johns Hopkins University from 1929 to his retirement in 1958. He has written a number of outstanding books, among them From the Stone Age to Christianity, and has contributed one way or another to almost a thousand volumes. Currently he has curtailed nearly all lecturing and teaching to fulfill a program of publications which includes over a dozen volumes and many shorter efforts.

Dr. Albright’s critical position is broadly liberal, but he has a strong conservative orientation on many issues. This epousal of conservative views as well as his rejection of extreme liberal views creates wide evangelical interest in his convictions.

Many of the evangelical movement’s younger Old Testament scholars have pursued doctoral studies under Dr. Albright’s teaching. In addressing the following questions to Dr. Albright, the editors of CHRISTIANITY TODAY reflect inquiries suggested by a number of Old Testament scholars, among them Dr. Oswald T. Allis, Dr. Gleason L. Archer, Jr., Dr. Clyde T. Francisco, Dr. David W. Kerr, Dr. Meredith G. Kline, Dr. Charles F. Pfeiffer, Dr. Kyle M. Yates, Dr. G. Douglas Young, and Dr. Edward J. Young.—ED.

Q. Where do you locate yourself in the contemporary theological spectrum?

A. My position remains in the middle—equally far from extreme conservatives and from extreme liberals. I am still growing more conservative on questions of date and authorship, historical background, and so forth, having moved considerably farther to the right, but I am even more strongly “liberal” on general problems of the history of theology, the use of evidence, the impossibility of man’s being able to formulate ultimate theological doctrines in human language.

Q. According to some reports you have become even more conservative since the Spring of 1961. What is the significance of these reports?

A. With respect to biblical tradition, this is quite true. In the Spring of 1961 I worked out details of my Goldenson Lecture on Samuel (published by the Hebrew Union College); that summer I completed my reconstruction of the background of Abraham; and during the past year I have made great progress on a more conservative approach to Job. These are only major examples of what I have been doing in both Old Testament and New Testament, especially in the latter, where my views tend to be more conservative than those of many professed conservatives in matters of date and authorship.

Q. What archaeological discoveries of recent times do you consider most significant?

A. Ugarit (Ras Shamrah) for early Hebrew literature and its date; Qumran (Dead Sea Scrolls) for all branches of biblical study (especially for early dating of New Testament books); Chenoboskion (Nag Hammadeh) for pre-Gnostic content of New Testament books.

Q. What do think of Dr. Cyrus H. Gordon’s contention that there is conclusive linguistic evidence of a parent culture common to both Hebrew and Greek civilizations and that this discovery is more important than the finding of the Dead Sea Scrolls?

A. Gordon’s work is often useful in appraising elements common to Northeast-Mediterranean cultures in the second millennium B.C. These common elements may be detected by archaeological and literary comparisons, but practically never by linguistic methods as such. I cannot accept any of his three successive decipherments of Linear A nor his explanations of early place and personal names in the Greek area as Semitic. The value of the Dead Sea Scrolls for biblical research is far greater than that of any other archaeological find or research based thereon.

Q. Do you stand by your conviction that, contrary to the liberal Protestant view of the past generation, every book of the New Testament could have been written by some contemporary of Jesus of Nazareth, rather than in the second century?

A. Rephrasing the question, I should answer that, in my opinion, every book of the New Testament was written by a baptized Jew between the forties and the eighties of the first century A.D. (very probably sometime between about 50 and 75 A.D.).

Q. In the article on “Return to Biblical Theology” (The Christian Century, Nov. 19, 1958), you stated: “Until 1 was twenty-one I had never met anyone whom I knew to be Jewish, but after nearly half a century of friendly association I am in some ways more at home in Jewish circles than anywhere else.” Now some persons, pointing to the basic difference in attitude of Jew and Christian toward the divine messiahship of Jesus, have found this statement puzzling. In what ways are you more at home in Jewish circles than anywhere else?

A. The attitude of Jews toward education and culture tends to be more intelligent than that of Christians; Jews also tend to have a keener feeling for moral and social problems. Christ said of spiritually insensitive people who flaunt his name, “Not every one that saith unto me, Lord, Lord, shall enter into the kingdom of heaven; but he that doeth the will of my Father which is in heaven. Many will say to me in that day, Lord, Lord, have we not prophesied in thy name? and in thy name have cast out devils? and in thy name done many wonderful works? And then will I profess unto them, I never knew you: depart from me, ye that work inquity.”

Q. You have somewhere remarked that Protestantism can be held in balance only by recognizing the permanent values in Catholicism and Judaism. Briefly what are these values, and do they imply that Judaism and Catholicism are on a parity with Protestantism?

A. Jews tend to have keener ethical and social conscience. Catholics tend to show greater reverence and greater humility. I am a convinced Protestant of Methodist background.

Q. You have stood out among modern scholars in emphasizing the confirmation archaeology gives to the historical trustworthiness of the Bible. Would you view a reference in the biblical narratives as presumptive evidence of historical facticity?

A. Certainly. In many cases, however, archaeological confirmation or illustration is necessary before we can understand the historical meaning of biblical narratives or allusions.

Q. What major problems remain by way of apparent conflict between the Bible and present archaeological data?

A. Major remaining problems mostly involve clarification of complex oral and/or written transmission of biblical texts.

Q. Is it the fact that carbon 14 is inaccurate for dating bones? Has carbon dating been tested by applying it to objects known to come from the Eighteenth Egyptian Dynasty (ca. 1500B.C.)?

A. Carbon 14 is almost totally useless in dating bones, which contain a minimum of carbon. We now have many thousands of carbon dates from all over the world, but dating material by inscriptions is nearly always more accurate than use of radiocarbon.

Q. Are there instances in which you are convinced that the biblical writers erred in matters of detail?

A. The question is not clear. Commentators have erred in detail; so have translators, copyists, ancient compilers of written texts, and collectors of oral tradition. Before them, “errors” were made in the process of transmitting oral and written tradition. In my opinion no national literature in the world has suffered so little as Israelite from these multiple sources of error. I am always surprised anew by what Nelson Glueck calls “the incredible historical memory of Israel.”

Q. Many Old Testament scholars still accept the results of source analysis (J, E, P, D, and so on). In what way has archaeology changed the attitude of biblical scholars from that which prevailed in the late nineteenth century?

A. Everybody admits the existence of different genres of literature in the Pentateuch: the narratives containing, more or less alternatively, the divine names Yahweh and Elohim; the priestly descriptions of buildings, rituals, and cultic regulations in Exodus-Leviticus; the “Second Law” in Deuteronomy. The Pentateuch is mostly in the same “dialect”—the literary language of Southern Israel between the tenth and the early sixth century B.C. (as we know positively from inscriptions). The spelling of our Hebrew text was gradually fixed between about 500 B.C. and A.D. 900 (after vowel points had been added). The study of the Dead Sea Scrolls has dealt a crushing blow to the minute critical analysis of the early books of the Bible that has prevailed since Wellhausen, by proving that there were different early recensions of the text and that the Masoretic text is too derivative to provide a basis for such minute “analysis.”

Q. What permanent significance do you attach to the Genesis creation narratives?

A. The narratives of Genesis 1–11 come from the hallowed past of the Hebrew people; they were sacred from the remotest times, and they acquired new meaning in biblical days under the Mosaic dispensation, which demythologized where necessary and added new spiritual meaning. I do not think that these narratives will ever lose their unequalled importance for a Christian picture of God in creation and history.

Q. In what respect may we term the stories of the patriarchs in Genesis historical?

A. See the first chapters of my Harper Torchbook, The Biblical Period from Abraham to Ezra, appearing in January, 1963. I maintain that the same approach holds for the phases not specifically included in my treatment. Briefly, I think that the patriarchal narratives were handed down, in general, by word of mouth in verse form, which might be preserved for centuries because of its fixed style and musical setting. Some oral tradition was undoubtedly transmitted in prose, and some very ancient written documents presumably were known. Oral tradition is subject to its own regularities of behavior, which make it more flexible and more easily dramatized than written tradition. It is thus far better suited to become the vehicle of basic religious instruction. The process of compiling prose narratives from poetic sources was at its height in the tenth century B.C.

Q. Scholars of evangelical persuasion are interested in the sense in which you view the Bible as the Word of God, and whether this view has scriptural sanction.

A. Certainly the Bible is the Word of God—but not in a magical sense; it cannot be used for divination cr for esoteric purposes, as is so often the case. The Bible contains the creative and prophetic revelation of God, but to understand its meaning, the most penetrating and comprehensive study has always been and still is needed. In the Bible itself the terms which are rendered “word” in English have a very wide range of meanings, which we have no right to disregard. Lighthearted acceptance of any one dogma about the meaning of “verbal inspiration” is dangerous in the extreme.

Q. Do you think that Israel became a nation under Mosaic monotheism with a covenant at Sinai, or rather agree with Martin Noth who thinks the first national covenant was made at Shechem?

A. I accept the tradition of the Book of Exodus. Moses, not Joshua, was the founder of Israel.

Q. Many passages in Isaiah 40–66 denounce idolatry as a current evil in Israel (for example, 44:9–20; 51:4–7; 65:2, 3; 66:17). How can these be reconciled with a theory of post-Exilic authorship, since idolatry admittedly was never reintroduced into Judah after the Restoration (as witness Ezra, Nehemiah and Malachi by implication)?

A. I do not think that anything in Isaiah 40–66 is later than the sixth century.

Q. Will you elaborate the implications, as you now see them, of your statement in December, 1955, that certain Qumran manuscripts “preserve textual elements going directly back to the original Deuteronomic Samuel, compiled toward the end of the seventh century B.C.”?

A. I agree with Martin Noth that Deuteronomy-II Kings (excluding Ruth) were compiled from older materials by an anonymous editor, whom I date (except for the last chapters of II Kings) in the reign of Josiah (ca. 640–609 B.C.). Many earlier conservative scholars dated the compilation of Judges-II Kings at about that time. The contents are, in the main, much older.

Q. Questions of lower criticism aside, when it comes to a criterion by which to judge of the accuracy and trustworthiness of the biblical record, do you recognize as final the authority of Scripture or do you consider yourself in respect to the principle of authority still in the school of Wellhausen?

A. “Authority of Scripture” is a valid theological principle, whereas the “School of Wellhausen” is only one of many ideological systems built on arbitrary philosophical postulates and baseless historical presuppositions.

Q. Do we have reason to expect future contributions from archaeology to be as significant for biblical scholarship as those in the past?

A. They should become more important all the time, since we are only beginning to utilize past discoveries adequately, and future discoveries may be as extraordinary as the Dead Sea Scrolls.

Q. To guide and stimulate young scholars, will you suggest some of the most urgent archaeological tasks before us today?

A. More and better scientific excavation, and more and better scholarship in interpreting finds.

Q. How can a young theological student become a member of a “digging team”?

A. By attending schools where there is a live archaeological interest and distinguishing himself in his study or in useful skills. He can also help raise money for an expedition.

Q. What is your general evaluation of neoorthodoxy as a theological emphasis?

A. Neoorthodoxy is so generous in its tolerance of philosophical approaches that I should hesitate to affiliate myself with any form of it. Personally I am a rational empiricist in my general approach to history. Many “neoorthodox” theologians support some form of Gnosticism or Neo-Platonism.

Q. Some evangelical interpreters are unsure of your attitude toward the historical character of supernatural events related in the Bible, in part because of statements in From the Stone Age to Christianity in which you assert that “in the presence of authentic mysteries” the historian’s duty is “to stop and not attempt to cross the threshold into a world where he has no right of citizenship” (1957 ed., p. 390); that “the historian … has no right to pass judgment on (the) historicity” of Jesus’ virgin birth and resurrection; and that “the historian, qua historian, must stop at the threshold, unable to enter the shrine of the Christian mysteria without removing his shoes …” (ibid., p. 399). Are you doubtful of the factuality and historicity of the supernatural birth and bodily resurrection of Jesus of Nazareth? Do you relegate these events to super-history or do you regard them as unique historical events?

A. I still subscribe to this position as an empirical historian. Theological truth is no less true because it is not the kind of truth that an archaeologist can validate.

Q. Do you consider yourself an orthodox Christian trinitarian?

A. Yes, but this does not mean that I pretend to understand the ultimate mysteries of divine being. One must, furthermore, never forget that “Person” of the Trinity has been authoritatively described by a number of different key words since apostolic times.

Q. What in general is your view of prophecy and miracles?

A. I believe in prophecy and miracles, but refuse to accept any confining theological definition of either. I believe that both continue to this day and that both are relative to the human scene in which they appear. Not all prophecy in the Bible can be validated, though the standard of validation is far higher than anything we find today. Some miracles of the Bible would not be considered as such today, and most miracles of today pass unnoticed. But the fact of prophecy and the fact of miracles are central to a living Christian faith, whatever may be thought of alleged individual miracles, ancient or modern. I believe in both prophecy and miracles as essential to Christian faith. What we mean by these terms changes constantly. Scientific medical triumphs of today were miracles once. I should not label every supposed prophecy and miracle of the Bible by this name, nor do I believe that prophecy and miracles came to an end with the canon. On the contrary’, God is just as active in history, in the life of the individual human being, and in the world of nature as ever.

Q. How do you view the Bible alongside the other literature of the world religions?

A. The Bible, as the revelation of God, remains absolutely unique, but we must not despise non-biblical religions or refuse to profit from their example.

END