The Christian character of T. S. Eliot’s poetry is a common subject for discussion in religious periodicals. Professor James Wesley Ingles has commented eloquently on this topic in his article, “Christian Elements in the Poetry of T. S. Eliot” (CHRISTIANITY TODAY, October 13, 1961). Nowhere is Eliot more explicit in delineating his Christian beliefs than in the short poem, “Journey of the Magi.” Here his grasp of the inherent soteriological truth, that Jesus Christ was born to die, makes relevant the reading of this poem at this Christmas season, when all the world concentrates on the manger, as if to blot out the cross.

In “Journey of the Magi” we hear the reminiscences of one of the Wise Men. Now an old man, he appears to be recounting his memoirs to an amanuensis. The words “but set down/This set down/This” are directed to the secretary, and the first five lines of the poem, enclosed in quotation marks, are a partial transcript of the record already written. This would seem to be a valid interpretation from the text, although Eliot in one of his essays has attributed these opening lines to a paraphrase of a sermon by Lancelot Andrewes (1555–1626), one of the translators of the Authorized Version. As it appears in the poem, however, the passage belongs to the aged Magian.

His attitude, shown in the first stanza, toward his memories is important to observe. He recalls very little about the journey that could be considered pleasant, even in the romance of retrospection. The season was “just the worst time of year.” The journey, “such a long journey.” The functionaries on whom he depended—the camels and the men who drove them—are remembered as having been “refractory.” The animals lay down in the melting snow, refusing to go any farther in their “galled, sore-footed” condition. Their drivers cursed and gambled and ran off, looking for liquor and women. Even the comforts of fire and human fellowship were denied the men from the East.

… the night-fires going out, and the lack of shelters, And the cities hostile and the towns unfriendly And the villages dirty and charging high prices: A hard time we had of it.

External forces opposed them in their quest for the newborn King. But the greater gnawing of dejection and doubt originated “with the voices singing in our ears, saying/That this was all folly.”

Eliot’s ambiguity in the second stanza is pervaded by Christian symbols. A whole day, the most important of the journey, comes to the mind of the narrator. It begins at dawn in “a temperate valley”—where the travelers might well have been tempted to give up their search—and ends “at evening, not a moment too soon.” Discouragement at the length of the journey and the hardships involved would have resulted in resignation from their mission, had the Wise Men not reached their destination when they did. Between the hours of sunrise and sunset much had been seen: “three trees on the low sky” that unmistakably forecast the scene at Calvary; “an old white horse” that gallops away into the meadow, possibly to await his Rider’s need for him (Rev. 6:2). In the village, one of those already described as “dirty and charging high prices,” the Wise Men find their own Vanity Fair. It is a tavern in which three men are seen “dicing for pieces of silver,/And … kicking the empty wine-skins.” Filled as it is with incisive statements on the wasteland of this world, Eliot’s poetry has no more striking picture of man’s frustrated existence than this. Of course, there is no information available from anyone in the tavern concerning the whereabouts of the Christ-Child. One could scarcely expect men who grovel in greed to know or care about the coming of their King, and so the Wise Men continue their pilgrimage to find “the place” on their own.

After all their struggle, success seems anti-climactic. In this one respect Eliot differs from the story in Matthew’s account, which tells us that the Wise Men “rejoiced with exceeding joy.” What must be the understatement of all time is the old man’s only comment upon that scene described in Matthew 2:11—“it was (you may say) satisfactory.”

How much more than merely “satisfactory” the experience was we may judge from the final stanza. First, the sight of the infant Redeemer did stamp a permanent impression upon the memory of the Magian, for although “all this was a long time ago,” he is certain that he would repeat the expedition. “I would do it again,” he says. Secondly, the significance of the Saviour’s birth was not lost upon the Wise Man. In his years of pondering the strange journey that took him to the Child before whom he opened his treasures, one question has played in his mind. It is the key question to his whole understanding of the mystery of the Incarnation: “Were we led all that way for/Birth or Death?” In coming to know the truth about God manifest in the flesh, he has learned that Birth and Death are no different when the cross shadows the cradle.

Moreover, in this Birth the Magian found birth, and it too was compounded with death, for

this Birth was

Hard and bitter agony for us, like Death, our death.

Much more must be seen in the worship of the Wise Men than a mere offering of gold, frankincense, and myrrh. It was, in fact, the turning-over of themselves, their treasures, their kingdoms. In such a transforming, transcending act there was “hard and bitter agony,” as the lust for gold yielded before the Lord of Glory. A death to self, to the coveting of possessions, is always painful. Yet, in the act of dying the Wise Men found new life.

The closing lines bring the story up-to-date. Upon returning to their homeland, the Magi found themselves “no longer at ease here, in the old dispensation,/With an alien people clutching their gods.” Eliot’s pilgrims, having once seen their King, are not content in the City of Destruction to which they have returned. One senses the reason in the words “the old dispensation.” Like believers today—and here the correspondence between Bunyan’s Christian and Eliot’s Wise Men dissolves—the Magi remained “in the world” but were no longer “of the world.” The old things had passed away; all had become new. Their countrymen appeared as strangers, “an alien people,” in the continuance of their pagan worship. The transformation in the lives of the Magi had been complete, and it had brought with it dissatisfaction with the old ways.

One thought, then, remains. It is Eliot’s final statement from the lips of the old Magian. “I should be glad of another death,” he informs us, and we note the wistful tone in his voice. In comprehending the paradox of Christian teaching, that spiritual birth and death are related, the Wise Man has also realized that physical death will again bring him before the King he once traveled so far to adore. This thought pleases him, and in glad anticipation of the close of his life, he contemplates again the eventful journey that so altered its course.

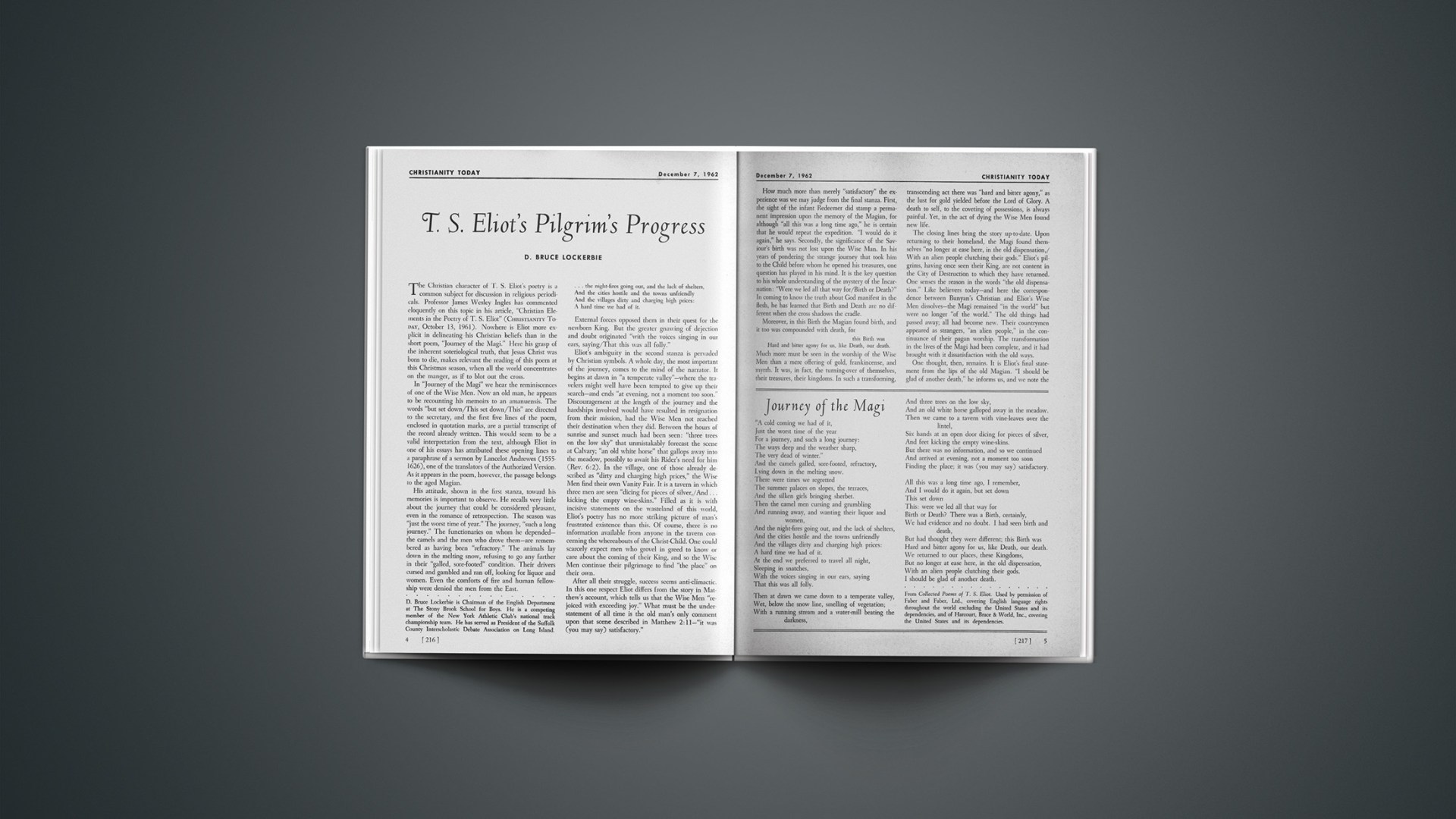

Journey of the Magi1From Collected Poems of T. S. Eliot. Used by permission of Faber and Faber, Ltd., covering English language rights throughout the world excluding the United States and its dependencies, and of Harcourt, Brace & World, Inc., covering the United States and its dependencies.

“A cold coming we had of it,

Just the worst time of the year

For a journey, and such a long journey:

The ways deep and the weather sharp,

The very dead of winter.”

And the camels galled, sore-footed, refractory,

Lying down in the melting snow.

There were times we regretted

The summer palaces on slopes, the terraces,

And the silken girls bringing sherbet.

Then the camel men cursing and grumbling

And running away, and wanting their liquor and women,

And the night-fires going out, and the lack of shelters,

And the cities hostile and the towns unfriendly

And the villages dirty and charging high prices:

A hard time we had of it.

At the end we preferred to travel all night,

Sleeping in snatches,

With the voices singing in our ears, saying

That this was all folly.

Then at dawn we came down to a temperate valley,

Wet, below the snow line, smelling of vegetation;

With a running stream and a water-mill beating the darkness,

And three trees on the low sky,

And an old white horse galloped away in the meadow.

Then we came to a tavern with vine-leaves over the lintel,

Six hands at an open door dicing for pieces of silver,

And feet kicking the empty wine-skins.

But there was no information, and so we continued

And arrived at evening, not a moment too soon

Finding the place; it was (you may say) satisfactory.

All this was a long time ago, I remember,

And I would do it again, but set down

This set down

This: were we led all that way for

Birth or Death? There was a Birth, certainly,

We had evidence and no doubt. I had seen birth and death,

But had thought they were different; this Birth was

Hard and bitter agony for us, like Death, our death.

We returned to our places, these Kingdoms,

But no longer at ease here, in the old dispensation,

With an alien people clutching their gods.

I should be glad of another death.

Contemporary readers may accept the poem as a sophisticated amplification of the familiar Bible story. Or we may interpret its symbolic message in the light of our own quest for salvation. We too must turn aside from the sensual pleasures that would prevent us from continuing our pilgrimage; we must reject the voices that cry “Folly” in our ears. We must overcome the base wallowing in sin that mires men in the tavern of this world. And we must be willing to seek Him when there is no one who can lead us to where he is.

In seeing Jesus Christ, in offering to him the treasure of our lives, we can be certain that his influence upon us will match his influence upon the Magi. We too shall see ourselves transformed, becoming new creatures as the old life dies and the new is born. But whether or not we sense an estrangement from the old ways depends upon how vividly we keep the image of Christ’s Lordship before us. Our Christmas devotion means nothing if we cannot honestly say, “I too should be glad of another death.”

END