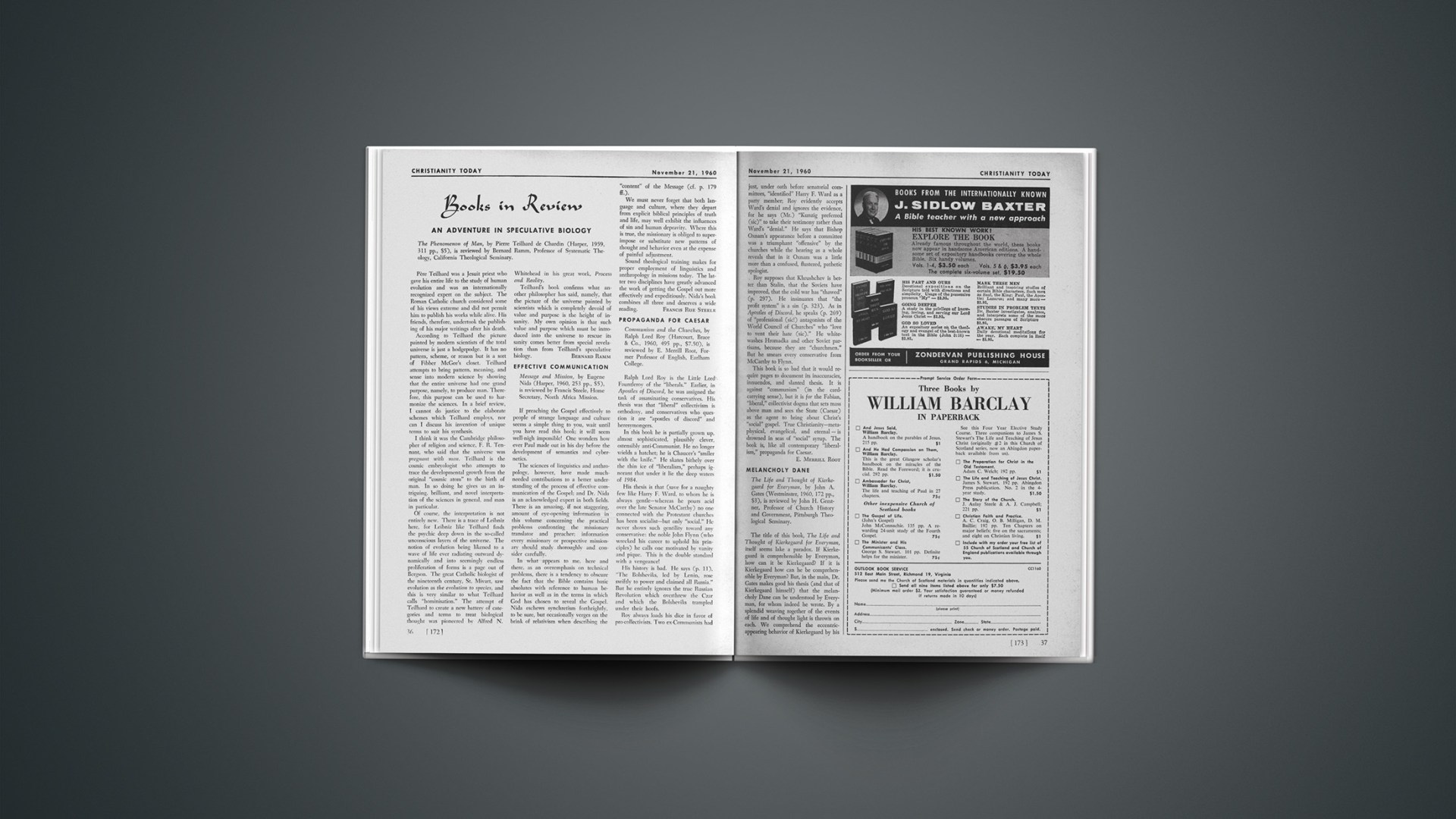

An Adventure In Speculative Biology

The Phenomenon of Man, by Pierre Teilhard de Chardin (Harper, 1959, 311 pp., $5), is reviewed by Bernard Ramm, Professor of Systematic Theology, California Theological Seminary.

Père Teilhard was a Jesuit priest who gave his entire life to the study of human evolution and was an internationally recognized expert on the subject. The Roman Catholic church considered some of his views extreme and did not permit him to publish his works while alive. His friends, therefore, undertook the publishing of his major writings after his death.

According to Teilhard the picture painted by modern scientists of the total universe is just a hodgepodge. It has no pattern, scheme, or reason but is a sort of Fibber McGee’s closet. Teilhard attempts to bring pattern, meaning, and sense into modern science by showing that the entire universe had one grand purpose, namely, to produce man. Therefore, this purpose can be used to harmonize the sciences. In a brief review, I cannot do justice to the elaborate schemes which Teilhard employs, nor can I discuss his invention of unique terms to suit his synthesis.

I think it was the Cambridge philosopher of religion and science, F. R. Tennant, who said that the universe was pregnant with man. Teilhard is the cosmic embryologist who attempts to trace the developmental growth from the original “cosmic atom” to the birth of man. In so doing he gives us an intriguing, brilliant, and novel interpretation of the sciences in general, and man in particular.

Of course, the interpretation is not entirely new. There is a trace of Leibniz here, for Leibniz like Teilhard finds the psychic deep down in the so-called unconscious layers of the universe. The notion of evolution being likened to a wave of life ever radiating outward dynamically and into seemingly endless proliferation of forms is a page out of Bergson. The great Catholic biologist of the nineteenth century, St. Mivart, saw evolution as the evolution to species, and this is very similar to what Teilhard calls “hominisation.” The attempt of Teilhard to create a new battery of categories and terms to treat biological thought was pioneered by Alfred N. Whitehead in his great work, Process and Reality.

Teilhard’s book confirms what another philosopher has said, namely, that the picture of the universe painted by scientists which is completely devoid of value and purpose is the height of insanity. My own opinion is that such value and purpose which must be introduced into the universe to rescue its sanity comes better from special revelation than from Teilhard’s speculative biology.

BERNARD RAMM

Effective Communication

Message and Mission, by Eugene Nida (Harper, 1960, 253 pp., $5), is reviewed by Francis Steele, Home Secretary, North Africa Mission.

If preaching the Gospel effectively to people of strange language and culture seems a simple thing to you, wait until you have read this book; it will seem well-nigh impossible! One wonders how ever Paul made out in his day before the development of semantics and cybernetics.

The sciences of linguistics and anthropology, however, have made much-needed contributions to a better understanding of the process of effective communication of the Gospel; and Dr. Nida is an acknowledged expert in both fields. There is an amazing, if not staggering, amount of eye-opening information in this volume concerning the practical problems confronting the missionary translator and preacher; information every missionary or prospective missionary should study thoroughly and consider carefully.

In what appears to me, here and there, as an overemphasis on technical problems, there is a tendency to obscure the fact that the Bible contains basic absolutes with reference to human behavior as well as in the terms in which God has chosen to reveal the Gospel. Nida eschews synchretism forthrightly, to be sure, but occasionally verges on the brink of relativism when describing the “content” of the Message (cf. p. 179 ff.).

We must never forget that both language and culture, where they depart from explicit biblical principles of truth and life, may well exhibit the influences of sin and human depravity. Where this is true, the missionary is obliged to superimpose or substitute new patterns of thought and behavior even at the expense of painful adjustment.

Sound theological training makes for proper employment of linguistics and anthropology in missions today. The latter two disciplines have greatly advanced the work of getting the Gospel out more effectively and expeditiously. Nida’s book combines all three and deserves a wide reading.

FRANCIS RUE STEELE

Propaganda For Caesar

Communism and the Churches, by Ralph Lord Roy (Harcourt, Brace & Co., 1960, 495 pp., $7.50), is reviewed by E. Merrill Root, Former Professor of English, Earlham College.

Ralph Lord Roy is the Little Lord Fauntleroy of the “liberals.” Earlier, in Apostles of Discord, he was assigned the task of assassinating conservatives. His thesis was that “liberal” collectivism is orthodoxy, and conservatives who question it are “apostles of discord” and heresymongers.

In this book he is partially grown up, almost sophisticated, plausibly clever, ostensibly anti-Communist. He no longer wields a hatchet; he is Chaucer’s “smiler with the knife.” He skates bithely over the thin ice of “liberalism,” perhaps ignorant that under it lie the deep waters of 1984.

His thesis is that (save for a naughty few like Harry F. Ward, to whom he is always gentle—whereas he pours acid over the late Senator McCarthy) no one connected with the Protestant churches has been socialist—but only “social.” He never shows such gentility toward any conservative: the noble John Flynn (who wrecked his career to uphold his principles) he calls one motivated by vanity and pique. This is the double standard with a vengeance!

His history is bad. He says (p. 11), “The Bolsheviks, led by Lenin, rose swiftly to power and claimed all Russia.” But he entirely ignores the true Russian Revolution which overthrew the Czar and which the Bolsheviks trampled under their hoofs.

Roy always loads his dice in favor of pro-collectivists. Two ex-Communists had just, under oath before senatorial committees, “identified” Harry F. Ward as a party member; Roy evidently accepts Ward’s denial and ignores the evidence, for he says (Mr.) “Kunzig preferred (sic)” to take their testimony rather than Ward’s “denial.” He says that Bishop Oxnam’s appearance before a committee was a triumphant “offensive” by the churches while the hearing as a whole reveals that in it Oxnam was a little more than a confused, flustered, pathetic apologist.

Roy supposes that Khrushchev is better than Stalin, that the Soviets have improved, that the cold war has “thawed” (p. 297). He insinuates that “the profit system” is a sin (p. 323). As in Apostles of Discord, he speaks (p. 269) of “professional (sic!) antagonists of the World Council of Churches” who “love to vent their hate (sic).” He whitewashes Hromadka and other Soviet partisans, because they are “churchmen.” But he smears every conservative from McCarthy to Flynn.

This book is so bad that it would require pages to document its inaccuracies, innuendos, and slanted thesis. It is against “communism” (in the card-carrying sense), but it is for the Fabian, “liberal,” collectivist dogma that sets mass above man and sees the State (Caesar) as the agent to bring about Christ’s “social” gospel. True Christianity—metaphysical, evangelical, and eternal—is drowned in seas of “social” syrup. The book is, like all contemporary “liberalism,” propaganda for Caesar.

E. MERRILL ROOT

Melancholy Dane

The Life and Thought of Kierkegaard for Everyman, by John A. Gates (Westminster, 1960, 172 pp., $3), is reviewed by John H. Gerstner, Professor of Church History and Government, Pittsburgh Theological Seminary.

The title of this book, The Life and Thought of Kierkegaard for Everyman, itself seems lake a paradox. If Kierkegaard is comprehensible by Everyman, how can it be Kierkegaard? If it is Kierkegaard how can he be comprehensible by Everyman? But, in the main, Dr. Gates makes good his thesis (and that of Kierkegaard himself) that the melancholy Dane can be understood by Everyman, for whom indeed he wrote. By a splendid weaving together of the events of life and of thought light is thrown on each. We comprehend the eccentric-appearing behavior of Kierkegaard by his thought and his paradoxical thought by his life.

If Dr. Gates has somewhat oversimplified the thinking of Kierkegaard, many scholars of our day over-complicate the Danish master. When most of us approach Kierkegaard in theological classrooms, we encounter an obscure thinker difficult to grasp at best and seemingly irrelevant at worst. This valuable little work, unique in its field, will serve as a corrective to any one-sidedness of the technical philosopher’s approach as well as a delightful introduction for Everyman.

JOHN H. GERSTNER

Cult Study

The Theology of the Major Sects, by John Gerstner (Baker, 1960, 188 pp., $3.95), is reviewed by Walter Martin, Director, Christian Research Institute, Inc.

With the evident acceleration of the missionary activities of non-Christian cults, many persons are now showing an interest in this needy field. The latest to procure literature on the subject is Professor of Church History and Government at Pittsburgh Theological Seminary, John Gerstner.

In 120 pages, Dr. Gerstner condenses the opinions, observations, and research of almost everyone who has written in the field for the last 50 years. The book contains a glossary of some of the terms utilized by the major cults, an appendix showing some of the doctrines of the cults compared with historic Christianity, and a chart of the doctrines of the sects similar to the old “Spirit of Truth and Spirit of Error” publication still in circulation. Dr. Gerstner has appended to this a selected bibliography.

According to the author, the volume was designed as a “handbook to provide ready reference material—a quick guide to the wealth of literature which expounds this subject.” The reviewer believes that he should have substituted the word “confuses” for “expounds,” for he would have been closer to the truth of the matter.

The fact is that about 80 per cent of the literature in this field is either outdated, inaccurate, or so lacking in trained research as to render it confusing and largely worthless as a means either of evangelizing cultists or refuting them. Dr. Gerstner has indeed compiled a great deal of information, but one wonders whether he has done actual field work of any scope among the cults and the cultists. The book does not convey that impression, and unfortunately it misrepresents the views of some of the people it purports to understand.

In his chapter on Seventh-day Adventism, for example, Dr. Gerstner accuses them of holding views they have publicly rejected concerning the “sinful nature” of Christ. He quotes a book from which the very statement he uses was expunged 15 years ago, and also quotes the 1957 yearbook as “their latest official statement.” He totally ignores Questions on Doctrine, the authorized expansion of the statement which repeatedly affirms the sinlessness of Christ’s nature (appendix, p. 127). Apparently, in this instance, as in others where he misrepresents the Adventists, he has not read carefully what they have claimed.

On the whole Dr. Gerstner’s book betrays the same weakness as Van Baalen’s (to which he frequently refers) and a majority of others (excepting Bach and Braden). He relies chiefly upon reading sources and apparently neglects fundamental research, methodology, and field works. The missionary infiltration of the cults on foreign fields is not covered nor are the methods of the cults.

It is the reviewer’s opinion that Dr. Gerstner’s abstract of the research of others, garnished by a glossary and an all-too-brief textual refutation, complemented by an appendix given to repetition, reveals unfamiliarity with the basic issues of cult activities, methods and theological intricacies.

The book indeed joins “a wealth of literature,” but it contributes little that is new in approach or content, and the author has sometimes relied upon sources which are, to say the least, questionable.

As a recommended text, it ranks with Van Baalen’s Chaos of Cults. To those unitiated in the field, it will prove useful on an introductory level, but as a serious study or analysis it is limited in its scope and understanding of a complex and growing field.

WALTER MARTIN

Reference Work

Atlas of the Classical World, edited by A. A. M. Van der Heyden and H. H. Scullard (Thomas Nelson & Sons, 1960, 221 pp., $15), is reviewed by Carl F. H. Henry.

Alongside the Atlas of the Bible (1956) and the Atlas of the Early Christian World (1958), the publishers have now issued the Atlas of the Classical World dealing with pagan antiquity. This is a prime reference work—73 maps in color, 475 photographs (many of them new), a concise text, and 24 pages of index.

CARL F. H. HENRY