Western man’s predicament in the last half of the twentieth century is viewed more and more as a mirror of humanity’s universal and continuing malady. In place of the one-time comfortable evolutionary speculations that linked man’s plight to an animal ancestry and inheritance, the newer appraisals emphasize rather man’s loss of spiritual relationship to the eternal world. While modern evaluations may produce novel conceptions of “original sin” and may even infuse into the notion of spiritual lostness something quite alien to the West’s inherited religious tradition, psychologically they often suggest a firmer sensitivity to the truth

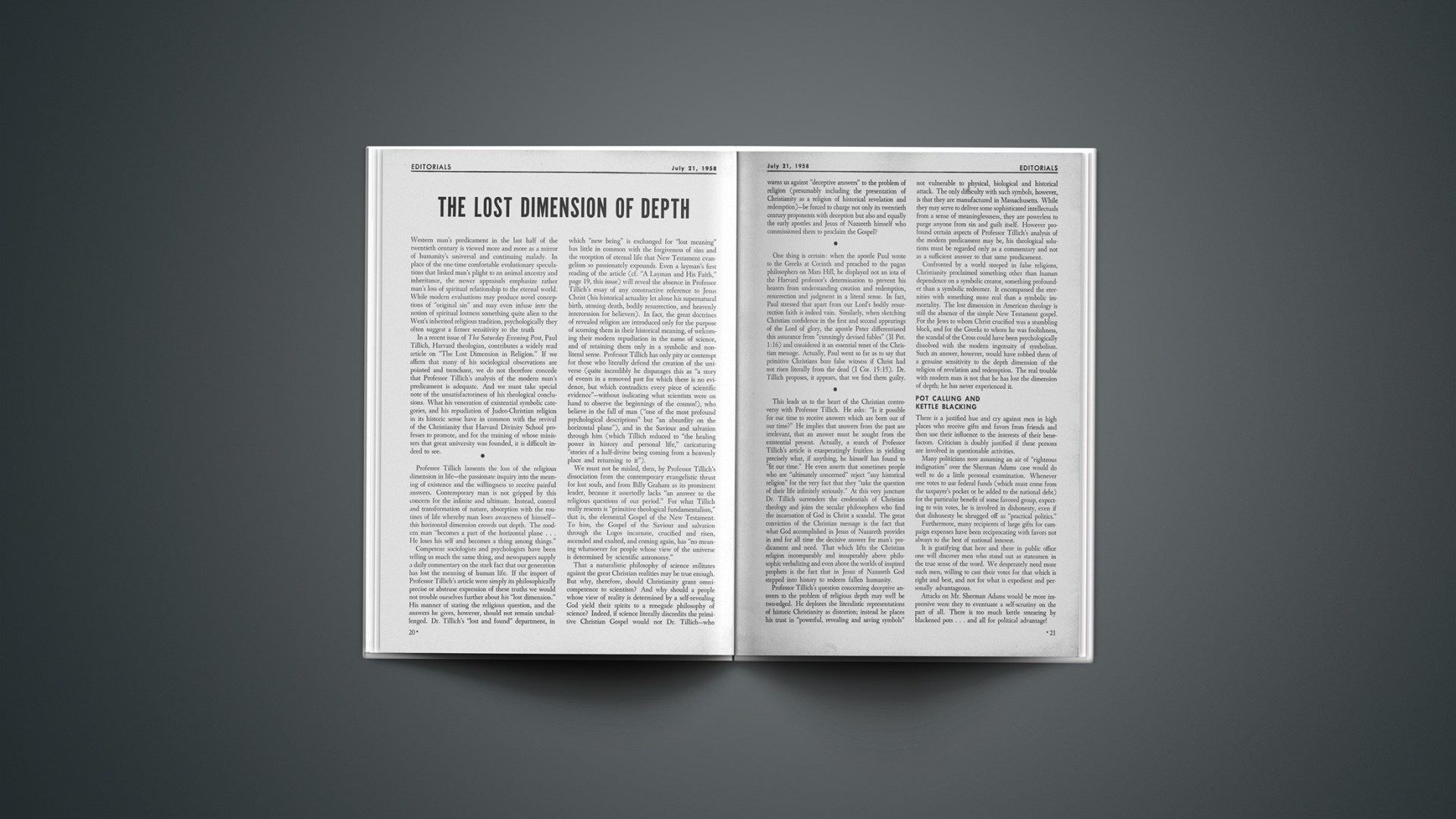

In a recent issue of The Saturday Evening Post, Paul Tillich, Harvard theologian, contributes a widely read article on “The Lost Dimension in Religion.” If we affirm that many of his sociological observations are pointed and trenchant, we do not therefore concede that Professor Tillich’s analysis of the modern man’s predicament is adequate. And we must take special note of the unsatisfactoriness of his theological conclusions. What his veneration of existential symbolic categories, and his repudiation of Judeo-Christian religion in its historic sense have in common with the revival of the Christianity that Harvard Divinity School professes to promote, and for the training of whose ministers that great university was founded, it is difficult indeed to see.

Professor Tillich laments the loss of the religious dimension in life—the passionate inquiry into the meaning of existence and the willingness to receive painful answers. Contemporary man is not gripped by this concern for the infinite and ultimate. Instead, control and transformation of nature, absorption with the routines of life whereby man loses awareness of himself—this horizontal dimension crowds out depth. The modern man “becomes a part of the horizontal plane … He loses his self and becomes a thing among things.”

Competent sociologists and psychologists have been telling us much the same thing, and newspapers supply a daily commentary on the stark fact that our generation has lost the meaning of human life. If the import of Professor Tillich’s article were simply its philosophically precise or abstruse expression of these truths we would not trouble ourselves further about his “lost dimension.” His manner of stating the religious question, and the answers he gives, however, should not remain unchallenged. Dr. Tillich’s “lost and found” department, in which “new being” is exchanged for “lost meaning” has little in common with the forgiveness of sins and the reception of eternal life that New Testament evangelism so passionately expounds. Even a layman’s first reading of the article (cf. “A Layman and His Faith,” page 19, this issue) will reveal the absence in Professor Tillich’s essay of any constructive reference to Jesus Christ (his historical actuality let alone his supernatural birth, atoning death, bodily resurrection, and heavenly intercession for believers). In fact, the great doctrines of revealed religion are introduced only for the purpose of scorning them in their historical meaning, of welcoming their modern repudiation in the name of science, and of retaining them only in a symbolic and non-literal sense. Professor Tillich has only pity or contempt for those who literally defend the creation of the universe (quite incredibly he disparages this as “a story of events in a removed past for which there is no evidence, but which contradicts every piece of scientific evidence”—without indicating what scientists were on hand to observe the beginnings of the cosmos!), who believe in the fall of man (“one of the most profound psychological descriptions” but “an absurdity on the horizontal plane”), and in the Saviour and salvation through him (which Tillich reduced to “the healing power in history and personal life,” caricaturing “stories of a half-divine being coming from a heavenly place and returning to it”).

We must not be misled, then, by Professor Tillich’s dissociation from the contemporary evangelistic thrust for lost souls, and from Billy Graham as its prominent leader, because it assertedly lacks “an answer to the religious questions of our period.” For what Tillich really resents is “primitive theological fundamentalism,” that is, the elemental Gospel of the New Testament. To him, the Gospel of the Saviour and salvation through the Logos incarnate, crucified and risen, ascended and exalted, and coming again, has “no meaning whatsoever for people whose view of the universe is determined by scientific astronomy.”

That a naturalistic philosophy of science militates against the great Christian realities may be true enough. But why, therefore, should Christianity grant omnicompetence to scientism? And why should a people whose view of reality is determined by a self-revealing God yield their spirits to a renegade philosophy of science? Indeed, if science literally discredits the primitive Christian Gospel would not Dr. Tillich—who warns us against “deceptive answers” to the problem of religion (presumably including the presentation of Christianity as a religion of historical revelation and redemption)—be forced to charge not only its twentieth century proponents with deception but also and equally the early apostles and Jesus of Nazareth himself who commissioned them to proclaim the Gospel?

One thing is certain: when the apostle Paul wrote to the Greeks at Corinth and preached to the pagan philosophers on Mars Hill, he displayed not an iota of the Harvard professor’s determination to prevent his hearers from understanding creation and redemption, resurrection and judgment in a literal sense. In fact, Paul stressed that apart from our Lord’s bodily resurrection faith is indeed vain. Similarly, when sketching Christian confidence in the first and second appearings of the Lord of glory, the apostle Peter differentiated this assurance from “cunningly devised fables” (2 Pet. 1:16) and considered it an essential tenet of the Christian message. Actually, Paul went so far as to say that primitive Christians bore false witness if Christ had not risen literally from the dead (1 Cor. 15:15). Dr. Tillich proposes, it appears, that we find them guilty.

This leads us to the heart of the Christian controversy with Professor Tillich. He asks: “Is it possible for our time to receive answers which are born out of our time?” He implies that answers from the past are irrelevant, that an answer must be sought from the existential present. Actually, a search of Professor Tillich’s article is exasperatingly fruitless in yielding precisely what, if anything, he himself has found to “fit our time.” He even asserts that sometimes people who are “ultimately concerned” reject “any historical religion” for the very fact that they “take the question of their life infinitely seriously.” At this very juncture Dr. Tillich surrenders the credentials of Christian theology and joins the secular philosophers who find the incarnation of God in Christ a scandal. The great conviction of the Christian message is the fact that what God accomplished in Jesus of Nazareth provides in and for all time the decisive answer for man’s predicament and need. That which lifts the Christian religion incomparably and insuperably above philosophic verbalizing and even above the worlds of inspired prophets is the fact that in Jesus of Nazareth God stepped into history to redeem fallen humanity.

Professor Tillich’s question concerning deceptive answers to the problem of religious depth may well be two-edged. He deplores the literalistic representations of historic Christianity as distortion; instead he places his trust in “powerful, revealing and saving symbols” not vulnerable to physical, biological and historical attack. The only difficulty with such symbols, however, is that they are manufactured in Massachusetts. While they may serve to deliver some sophisticated intellectuals from a sense of meaninglessness, they are powerless to purge anyone from sin and guilt itself. However profound certain aspects of Professor Tillich’s analysis of the modern predicament may be, his theological solutions must be regarded only as a commentary and not as a sufficient answer to that same predicament.

Confronted by a world steeped in false religions, Christianity proclaimed something other than human dependence on a symbolic creator, something profounder than a symbolic redeemer. It encompassed the eternities with something more real than a symbolic immortality. The lost dimension in American theology is still the absence of the simple New Testament gospel. For the Jews to whom Christ crucified was a stumbling block, and for the Greeks to whom he was foolishness, the scandal of the Cross could have been psychologically dissolved with the modern ingenuity of symbolism. Such an answer, however, would have robbed them of a genuine sensitivity to the depth dimension of the religion of revelation and redemption. The real trouble with modern man is not that he has lost the dimension of depth; he has never experienced it.

There is a justified hue and cry against men in high places who receive gifts and favors from friends and then use their influence to the interests of their benefactors. Criticism is doubly justified if these persons are involved in questionable activities.

Many politicians now assuming an air of “righteous indignation” over the Sherman Adams case would do well to do a little personal examination. Whenever one votes to use federal funds (which must come from the taxpayer’s pocket or be added to the national debt) for the particular benefit of some favored group, expecting to win votes, he is involved in dishonesty, even if that dishonesty be shrugged off as “practical politics.”

Furthermore, many recipients of large gifts for campaign expenses have been reciprocating with favors not always to the best of national interest.

It is gratifying that here and there in public office one will discover men who stand out as statesmen in the true sense of the word. We desperately need more such men, willing to cast their votes for that which is right and best, and not for what is expedient and personally advantageous.

Attacks on Mr. Sherman Adams would be more impressive were they to eventuate a self-scrutiny on the part of all. There is too much kettle smearing by blackened pots … and all for political advantage!