Editor’s note: With Terminator Salvation opening in theatres this week, we asked Peter T. Chattaway—a self-professed Terminator geek—to write an essay about the spiritual themes in the franchise, which he has seen since the first film released in 1984.

Whenever people ask me what my favorite Christmas movie is, I tell them it’s The Terminator—and I’m only half-joking.

The film, which celebrates its 25th anniversary later this year, is not exactly a religious movie or even a holiday movie on any obvious level. It’s an R-rated sci-fi action film with plenty of violence, a fair bit of profanity, and a sex scene that was standard fare for modestly-priced B-movies of that time. And yet, there is something about the storyline, written by director James Cameron, that has always brought the Nativity to mind.

The story concerns a man from the future named Kyle Reese (Michael Biehn) who comes back in time to tell a woman named Sarah Connor (Linda Hamilton) four things: the machines created to control our defense systems will become self-aware; the machines will launch a full-scale war to destroy the human race; humanity will be saved under the leadership of Sarah’s son John; and a cyborg called a Terminator (Arnold Schwarzenegger) has been sent back in time to kill Sarah so that her son John can never be born.

Kyle has thus been sent back in time to protect Sarah, and, although he does not know it, he will also become John’s father. And so, in an admittedly imprecise way, the film concerns an Annunciation of sorts; and as the Terminator, bent on finding Sarah and killing her, kills everyone else who happens to get in his way, the film evokes parallels to the slaughter of the innocents in Bethlehem as well. Just as the birth of Christ took place against the backdrop of a cosmic war in which the final outcome was never really in doubt, so too the birth of John Connor is soaked in the blood of battles he is destined to fight.

(It is tempting to suggest that John Connor’s initials might have messianic parallels, too—but they are also the initials of writer-director Cameron, so who knows?)

Complicating matters

The sequels have complicated matters in a number of ways, as more robotic assassins and more protectors have come back in time to fight over the life of John Connor, but the biblical, mythic and religious allusions remain. The films—and the short-lived TV series The Sarah Connor Chronicles, which lasted two seasons before it was officially cancelled earlier this week—have also reflected the increasingly sophisticated nature of the world, and how we perceive our place in it.

Take politics, for example. The original film came out in 1984, when fear of a nuclear apocalypse was all over the popular culture, from movies like WarGames and the Mad Max flicks to TV shows like Threads and The Day After. For young Christians like me, the fatalism of the era was amplified by the end-times themes that filled Christian music, films, and comic books at that time. In that climate, The Terminator suggested that, yes, a disastrous war would happen—but we would ultimately pull through it and survive.

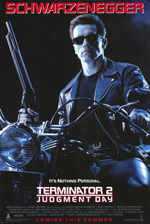

By the time Cameron wrote and directed the second film, Terminator 2: Judgment Day, in 1991, the Berlin Wall had fallen and the Cold War was over—and so, this time, the franchise went in a more optimistic direction. With the assistance of a new Terminator (Schwarzenegger again) who has been re-programmed to help them, Sarah and her young son John (Edward Furlong) are able to destroy the lab that was fated to create the machines of the future. The apocalypse, we are led to believe, will never happen now.

But then came Terminator 3: Rise of the Machines, in 2003—less than two years after the 9/11 terrorist attacks. The hopefulness of the previous film gave way to the idea that the war with the machines is “inevitable”—and that it cannot be prevented, because the forces that want to attack us are radically decentralized. What is more, we are now told that Connor’s future victory was not so final after all—indeed, we are told that he was killed in the future, or at least in one version of the future.

And so, in the new film, Terminator Salvation, the adult John Connor (Christian Bale) openly worries that he may not be able to win the war any more; he argues with his fellow military leaders over whether they should “stay the course,” a term often invoked during debates over the “war on terror”; and he insists that the Resistance should not adopt the methods of the enemy, otherwise “what’s the point?”

If the original film had a clear set of allegorical parallels, the sequels have been harder to pin down in that sort of way. For example, all of them have used the term “Judgment Day” to describe that moment when nuclear missiles rained down on all the world’s cities and the war with the machines began—but who, exactly, was doing the judging?

Relevant themes

Still, even without a clear biblical template, the sequels have definitely explored some issues of pressing importance to the modern Christian moviegoer:

The human-machine relationship. From cell phones to iPods, technology is playing a bigger and bigger part of our lives, to the point where some people have said that we are all becoming de facto cyborgs ourselves. The original film makes humorous references to pagers and answering machines, both of which were fairly new at the time, as well as the bigger, factory-sized machines that make such devices possible.

In this increasingly mechanized and technological world, it is more important than ever that we hold on to something spiritual, to the thing that makes us uniquely human; in Terminator Salvation, a teenaged Kyle Reese (Anton Yelchin) points to his head and his heart and tells his fellow prisoners to “stay alive, in here and in here.” But humanity is no mere spiritual abstraction; it is also rooted in the world of organic, physical life. So the people in these films love each other, have children together, and die for each other sacrificially.

The source of meaning and morality. In the first two sequels, John Connor and his wife-to-be, Kate Brewster (Claire Danes), are assisted by Terminators that have been re-programmed to protect them—and they ask these robots if there is anything more to them than their programming. Are the Terminators “worried” about dying? If John and Kate are killed, will that “mean anything” to them? Faced with such questions, the Terminators betray little emotion, and reply simply that they would have no reason to exist if John and Kate died, and that they need to “stay functional” in order to keep their human masters alive.

But there is more to a meaningful life than simply following your programming, and both T2 and T3 end on notes which suggest that the “good” Terminators have achieved something resembling free will; in both films, the Terminator goes beyond the orders he has been given and sacrifices himself for the greater good, even though he didn’t have to.

T2, in particular, goes even further and suggests that the Terminator of that film has learned “the value of human life.” Interestingly, though, when John initially tells the Terminator it is wrong to kill people, he can’t think of a reason beyond “Because you just can’t, okay?” It isn’t until the TV series The Sarah Connor Chronicles that a former FBI agent named James Ellison (played by the openly Christian Richard T. Jones) explains to a Terminator that it is wrong to kill because human life is made in the image of God and is therefore sacred.

And so, just as the re-programmed Terminators derive their meaning partly from the ones who have programmed them, but also partly from their freedom to go beyond their programming, so too we humans derive our meaning from the One who breathed life into us, and from our ability to exercise our free will in his service.

Destiny, prophecy and fatalism. The future is not set, and there is no fate but what we make for ourselves. So say several characters in each of these films, and yet, these characters don’t always behave as though they truly believe this. After all, John Connor sent the adult Kyle Reese back in time to become his father—and much of the new film revolves around John’s conviction that the teenaged Kyle needs to be rescued so that he can fulfill that destiny.

The films even play with the idea that efforts to change the future will just make things worse. In a couple of deleted scenes from the original film (available on some versions of the DVD), Sarah convinces Kyle that they should destroy the company that built the machines, to prevent the machines from being born—just as the machines are trying to kill Sarah to prevent John from being born. But, as we also see in T2, all Sarah ends up doing is luring the Terminator to one of the company’s factories—thereby guaranteeing that the technology which makes the machines possible will end up in that company’s hands.

In this, the films sometimes resemble Greek myth more than anything biblical. (T3 makes its debt to the Greeks explicit when the general who puts the machines in charge on Judgment Day tells his daughter, “I opened Pandora’s Box.”) To the Greeks, fate was unavoidable, and efforts to prevent a prophecy from coming true usually ended up fulfilling it.

And yet, the films resist fatalism. Just as the biblical prophecies often came with a call to repentance or an assurance that salvation was waiting on the other side of judgment, so too the Terminator films stubbornly cling to hope.

Death is certain, but human life remains precious nonetheless. The human spirit cannot be defeated or assimilated by machines. And, as the newest film makes especially clear, we can never rule out the possibility that we will get a “second chance.”

Copyright © 2009 Christianity Today. Click for reprint information.