In this series

One word floated forebodingly between parentheses throughout promotional material for the 2021 International Religious Freedom (IRF) Summit:

Invited.

Following the names of Nancy Pelosi, Antony Blinken, and Samantha Power, it indicated uncertainty if the key Democratic stalwarts would participate.

As the approximately 1,200 registered attendees arrived, the distributed official program still did not include the current House speaker, secretary of state, or USAID administrator.

However, Mike Pompeo, Blinken’s predecessor at the US State Department, had a keynote address from the stage.

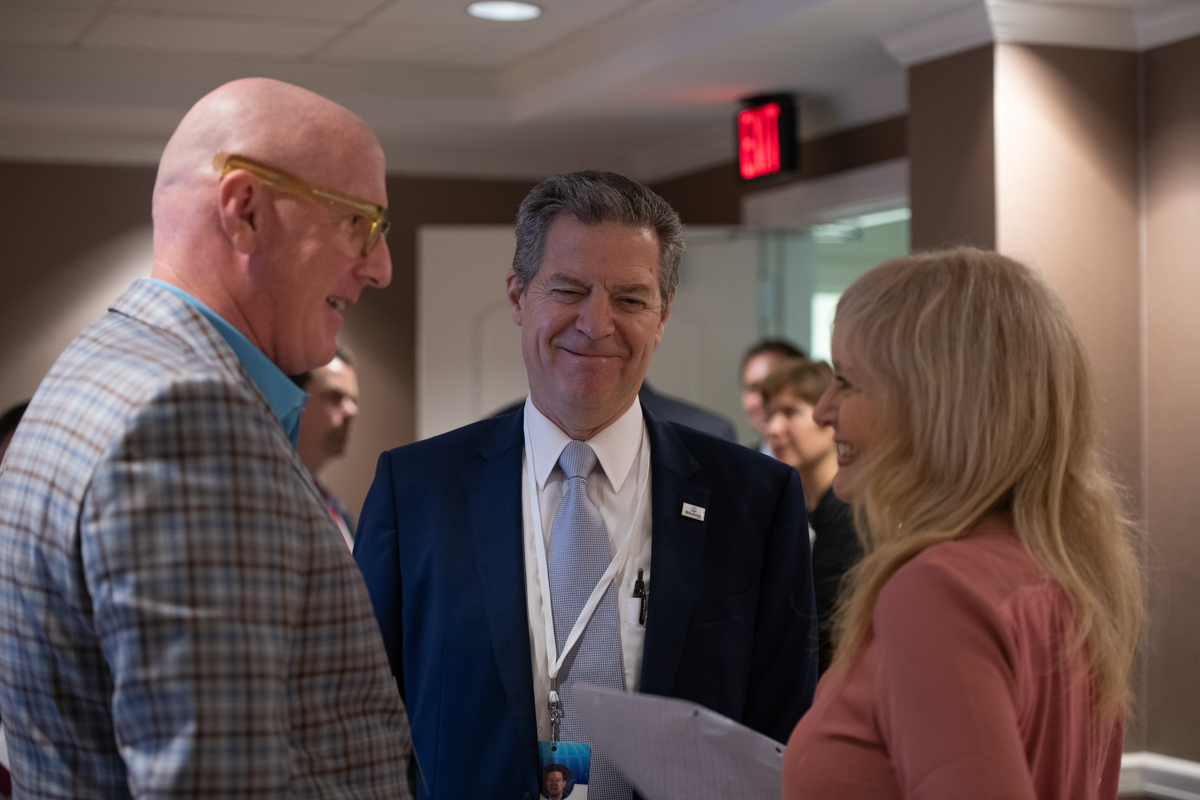

“There were a lot of questions heading into this summit, with a lot of hesitancy from the Biden people,” summit co-chair Sam Brownback told CT. “But we worked hard to make it bipartisan.”

Unlike the previous two ministerial meetings held in Washington, DC (and a third held virtually in Poland), this year’s IRF gathering was organized by civil society, not governments.

Brownback, the US ambassador-at-large for international religious freedom during the Trump administration, was now a private citizen. He partnered with Katrina Lantos Swett, former chair of the US Commission on International Religious Freedom, who was appointed by former Democratic senator Harry Reid.

Brownback chased the Republicans, and Lantos Swett the Democrats. Their friendship, Pam Pryor, senior advisor to the summit, told CT, is the “gold standard” in bipartisan cooperation.

In the end, Lantos Swett was relatively successful. Unable to appear in person, Pelosi, Blinken, and Power all provided prerecorded remarks.

“The summit demonstrates our ironclad commitment to international religious freedom,” stated Pelosi, “which transcends party and politics.”

The executive branch agreed.

“The US is committed to advance human rights,” stated Blinken, “and religious freedom is a vital component of our diplomacy.”

As did the leader of a key implementing organ, the US Agency for International Development (USAID).

“The fight for international religious freedom is not just a reflection of who we are as Americans, but of strategic national interest to the United States and a key foreign policy objective,” stated Power. “The Biden-Harris administration is dedicated to its protection and advancement, at home and around the world.”

Brownback felt vindicated.

He and Lantos Swett balanced Republican and Democratic IRF supporters in Congress, such as Chris Smith (R-NJ) and Henry Cuellar (D-TX) in the House of Representatives and Chris Coons (D-DE) and James Lankford (R-OK) in the Senate. They brought together advocates both right and left of center, such as Tony Perkins of the Family Research Council and Zeenat Rahman of the Inclusive America Project.

And between the 81 convening partners, every major religion of the world was represented.

“All of this together convinced the new administration that this is a broad movement, and that they wanted to be a part of it,” Brownback told CT.

“And they are.”

While scheduling did not permit Pelosi, Blinken, and Power to appear on stage, in-person proof was provided by Melissa Rogers, executive director of the White House Office of Faith-Based and Neighborhood Partnerships.

She also provided the news that summit participants were waiting for and chatting about in the hallways.

Bringing “warm greetings” from President Joe Biden, she said he would appoint the next IRF ambassador in “the coming weeks.”

While both George W. Bush and Barack Obama tarried as presidents in making their nominations, Trump took only six months. Biden is approaching the same mark.

Rogers also said the administration would “maintain the momentum” from previous ministerials and support the 2022 ministerial hosted by the United Kingdom in London. (Brazil has been scheduled to host in 2021.)

“Your work is vital, and you hold us accountable,” she said to the audience. “There is so much common ground on religious freedom, and so much good we can all do together.”

At the summit, however, this depended on the avoidance of domestic politics, said Peter Burns, the event’s executive director. Over two months the organizing committee solidified 10 panel discussions, organized by topic—not region—in order to be as broad as possible.

China, Nigeria, and Pakistan were nonetheless frequent targets throughout. Various participants highlighted Uyghur Muslims as monitored by malign technology, Nigerian Christians as victims of genocide, and Ahmadi Muslims as subjects of legal structures of discrimination.

Positive examples were also highlighted. An ecumenical prayer service brought together Mideast Christians. Philanthropy multiplied the concept of “covenantal pluralism.” And Kazakhstan signed a new agreement to educate both its clerics and its police on religious freedom and the rule of law.

“Tony Perkins and Samantha Power are at the same event, saying the same things, differently,” said Burns. “It’s really cool.”

But with such high-level political participation, partisan talking points were inevitable.

Pompeo criticized Biden for prioritizing climate change over religious freedom. He called the summit a “God-driven” continuation of Trump’s work. And he celebrated the United Arab Emirates’s opening of an embassy in Israel.

Rogers highlighted Biden’s reversal of Trump’s restrictions on Muslim and African immigration. She emphasized the importance of LGBT rights within the panoply of religious freedom. And Power called out Israel within her list of violating nations.

More substantive was the debate over the place of religious freedom within human rights overall.

“Oppression always begins against religious freedom,” said Pompeo, “leads to the loss of other civil and political rights, and can even come to include genocide.”

Democrats emphasized a “nesting” approach.

“The freedoms to speak freely, to assemble freely, and to advocate your cause to political leaders are interdependent,” said Power. “Religious freedom cannot exist without them.”

David Saperstein, the Jewish rabbi who preceded Brownback as IRF ambassador, tried to balance the perspectives from the stage.

“You cannot have freedom of religion if you do not have freedom of speech, press, and association,” he said. “But conversely, you cannot have these rights without freedom of religion and conscience.”

Overall, the attendance and sponsorships titled rightward, and Pompeo’s address solicited more robust applause than those from Democratic leaders. But Saperstein reminded everyone of 1998, when the International Religious Freedom Act (IRFA) moved through Congress without a single dissenting vote.

“IRFA was needed because religious freedom was a forgotten stepchild in the human rights movement,” he said. “Twenty-three years later, what we did worked.”

And for this, Brownback was pleased.

Having previously told CT that the last ministerial felt like Christmas, he was asked if this gathering felt like Easter.

“No, more like Pentecost,” he replied, after a brief pause.

“The spirit here is very peaceful, very pleasant—and very broad.”