When the US economy shut down in March due to COVID-19, financial predictions for churches and other ministries were dire. But a new survey suggests those predictions may have been overblown.

Most evangelical churches and ministries saw giving remain steady or grow during the height of stay-at-home restrictions, according to a survey of more than 1,300 Christian ministries released last week by the Evangelical Council for Financial Accountability (ECFA).

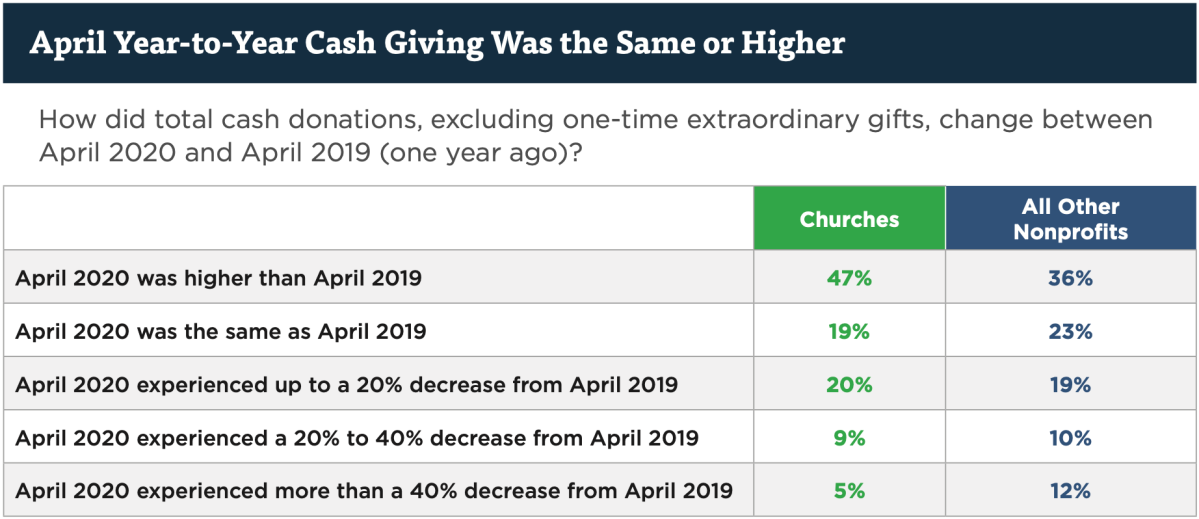

Among those surveyed, total cash giving in April 2020 equaled or surpassed April 2019 giving levels at 66 percent of churches and 59 percent of nonprofits. An even greater percentage of churches (72%) and other Christian nonprofits (61%) said their April 2020 cash gifts met or exceeded January 2020 levels, when the economy was booming and the stock market’s Dow Jones Industrial Average was approaching its all-time high.

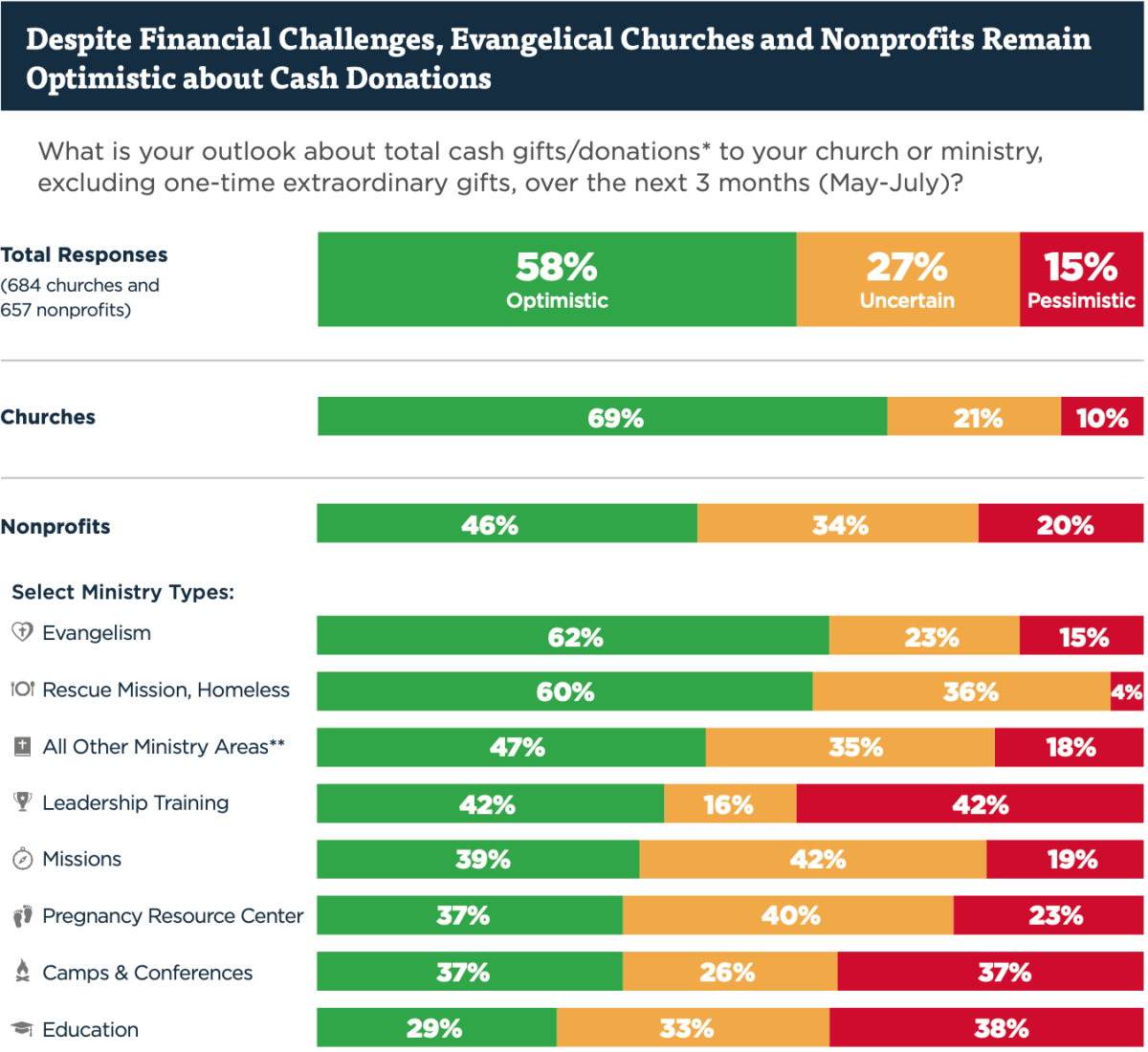

Those healthy giving levels have translated into economic optimism. More than half of the leaders were optimistic about anticipated cash gifts in May through July, while 27 percent were uncertain, and just 15 percent were pessimistic.

ECFA analyst Warren Bird told Christianity Today that churches and other nonprofits with cash on hand may want to consider putting their “money to work in doing ministry” rather than continuing “to hold [their] breath in fear that [their] circumstance is unusual and the bottom is just about to fall out.”

That’s a different outlook than ministries had two months ago. The State of the Plate poll, released April 23, found 65 percent of churches had seen giving decreases since mid-March. “For pastors and church staff, there will be difficult days ahead,” predicted State of the Plate founder Brian Kluth. Similarly, the Barna Group reported in a March podcast that 62 percent of US pastors said giving was down at their churches.

But the initial economic nosedive reversed in the span of a month as giving picked back up and Congress made small business loans available through the Paycheck Protection Program. (Sixty percent of churches and 81 percent of other Christian nonprofits either applied or planned to apply for one of those loans, according to the ECFA survey.)

For analysts, the key questions now are whether the positive outlook will hold and if any segments of the Christian world are being left behind.

The situation at Southridge Church in San Jose, California, has paralleled national trends. Giving dipped 25 percent in March, pastor Micaiah Irmler said, before picking back up in April and expanding in May. The congregation, which has conducted drive-in services during the pandemic, has a $580,000 annual budget and is in the midst of a capital campaign to purchase its first building.

Southridge’s giving has moved almost entirely online because of the coronavirus, up from about two-thirds online before the pandemic. Nationally, ECFA found 64 percent of churches saw an increased percentage of online giving between January and April.

“From what I’m hearing here in the Silicon Valley, we’re not going to be hit that hard,” Irmler said of the church’s finances. His greatest uncertainty involves Bay Area tech companies like Google and Twitter that decided during the pandemic to let many employees work from home permanently. “The only thing that has me somewhat nervous,” he said, is how many church members “might move out of our area” to decrease their cost of living.

Despite the overall optimism, ECFA’s findings were not all positive. About 1 in 5 churches (18%) and Christian nonprofits (20%) have established hiring freezes for nonessential roles. Eleven percent of churches and 14 percent of other nonprofits have reduced the number or hours of part-time staff.

Among Christian nonprofits, smaller organizations are less optimistic about cash gifts than their larger counterparts. Forty-six percent of nonprofits with annual budgets of under $500,000 expressed optimism about gifts in May through July. The number fell to 40 percent among nonprofits with budgets from $500,000 to $999,999. Optimism was higher in all other budget categories, peaking at 67 percent for nonprofits with budgets over $10 million. (Among churches, optimism levels were similar across all budget sizes, around 70 percent.)

Raleigh Sadler, executive director of the small Chicago-based anti-human-trafficking ministry Let My People Go (LMPG), expressed tempered optimism about the organization’s financial outlook. Between March and mid-May, the ministry’s receipts dipped 40 percent before beginning an upward trajectory in late May. LMPG has pursued larger donors to fill the gap as it waits for small and mid-size givers to recover financially.

Initially, “everyone was starting to lose their jobs,” said Sadler, LMPG’s only full-time employee. “People were scared. Everyone was uncertain, so they were pulling their purse strings.”

A segment of the evangelical world where economic hardship may not be reflected in ECFA’s report is African American churches. Bird told CT he isn’t aware of any research that examines the correlation between ethnicity and church giving during the coronavirus pandemic. However, the COVID-19 hospitalization rate for African Americans is approximately 4.5 times that of white Americans, according to the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Anecdotal evidence suggests the disproportionate impact of the coronavirus has taken a toll on black churches, many of which struggled to apply for or receive stimulus grants.

America’s largest black Pentecostal denomination, the Church of God in Christ, has seen seven of its bishops die from coronavirus, ABC News reported. Pastor A. R. Bernard of Christian Cultural Center in Brooklyn, New York, said the pandemic caught “many traditional black churches” off-guard because they lacked a “digital footprint” that permitted them to move worship and giving online with ease.

Still, the overall financial story for churches and ministries—at least for now—is reflected in the ECFA report’s title: “Optimism Outweighs Uncertainty.” ECFA will continue to monitor church and ministry finances during the pandemic, with a new report every quarter for the next year.

David Roach is a writer in Nashville.