As the US outlook around the coronavirus pandemic changes day by day, pastors are quickly adjusting their expectations about how the disruptions will impact their ministry.

Oregon pastor Tyler Braun explained that “on top of just navigating the right-now urgency of how to pivot”—the push to move services and giving and small groups online—pastors are grappling with the inevitable fallout on their members and community.

At New Harvest Church, where he leads worship and family ministries, Braun worries people will be forced to experience grief in isolation, lose out on finances, and face the coronavirus restrictions “well into the summer.”

A new survey by Barna Research found over the course of just a week, most church leaders went from thinking they’d be back to meeting as usual in late or March or April (52%), to projecting the changes would extend to May or longer (68%).

“There is this realism that’s setting in,” said David Kinnaman, Barna Group president.

But while most pastors are realistic, they’re also optimistic, according to Kinnaman. “One of the cool things about pastors we’ve learned over the years is that they are by job description and by disposition more upbeat, positive, hope-filled people,” he said. “So they are often pretty capable of putting a good face in a tough situation, and they, like other leaders, are going to face a lot of tough decisions in the coming weeks as the crisis continues.”

Though most had already called off normal activities at church, pastors also implemented swift changes in policies around smaller group meetings over the past several days.

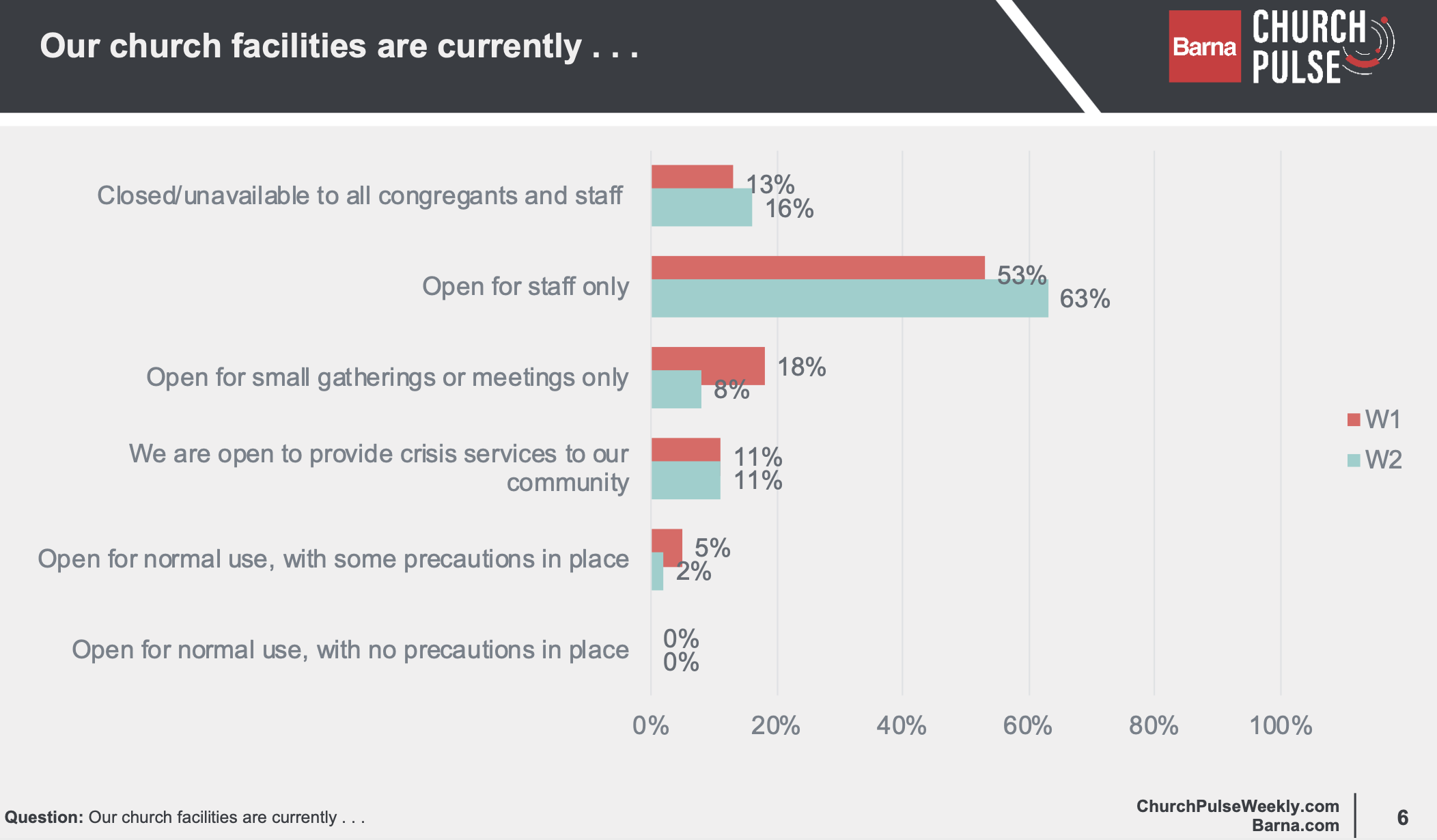

The percentage who still allow the church building to be used for “small meetings and gatherings” has dropped by about half (from 18% to 8%), according to Barna’s Church Pulse survey, hearing from 434 Protestant senior pastors and executive pastors in the US. A plurality say the church staff will be working remotely for the foreseeable future (up from 25% to 40%).

The question of restrictions (not just for worship but also staff meetings, Bible studies, even the group assembled to livestream services) has been an urgent one for pastors as more stories emerge of coronavirus spreading in church settings like choir practices and funerals.

A recent poll conducted by Denison University political scientist Paul Djupe and two fellow researchers found as many as 17 percent of US worshipers across traditions were still attending in-person gatherings of some sort as of early last week.

Compared to other traditions, evangelicals weren’t significantly more likely to say their churches were still open, but those who also ascribe to the prosperity gospel do have stronger feelings against churches closing to comply with government orders, a case which played out in Tampa on Monday. Nearly half of evangelicals with prosperity gospel beliefs agreed that “freedom to worship is too important to close in-person religious services due to the coronavirus even if more people die as a result.”

At this point, the vast majority of US Protestant pastors have closed their church doors and understand that ministry will be disrupted for months ahead. So the pressing questions have shifted to the state of their congregation as a whole, and what they as leaders can do to shepherd their disparate flock through an unprecedented time.

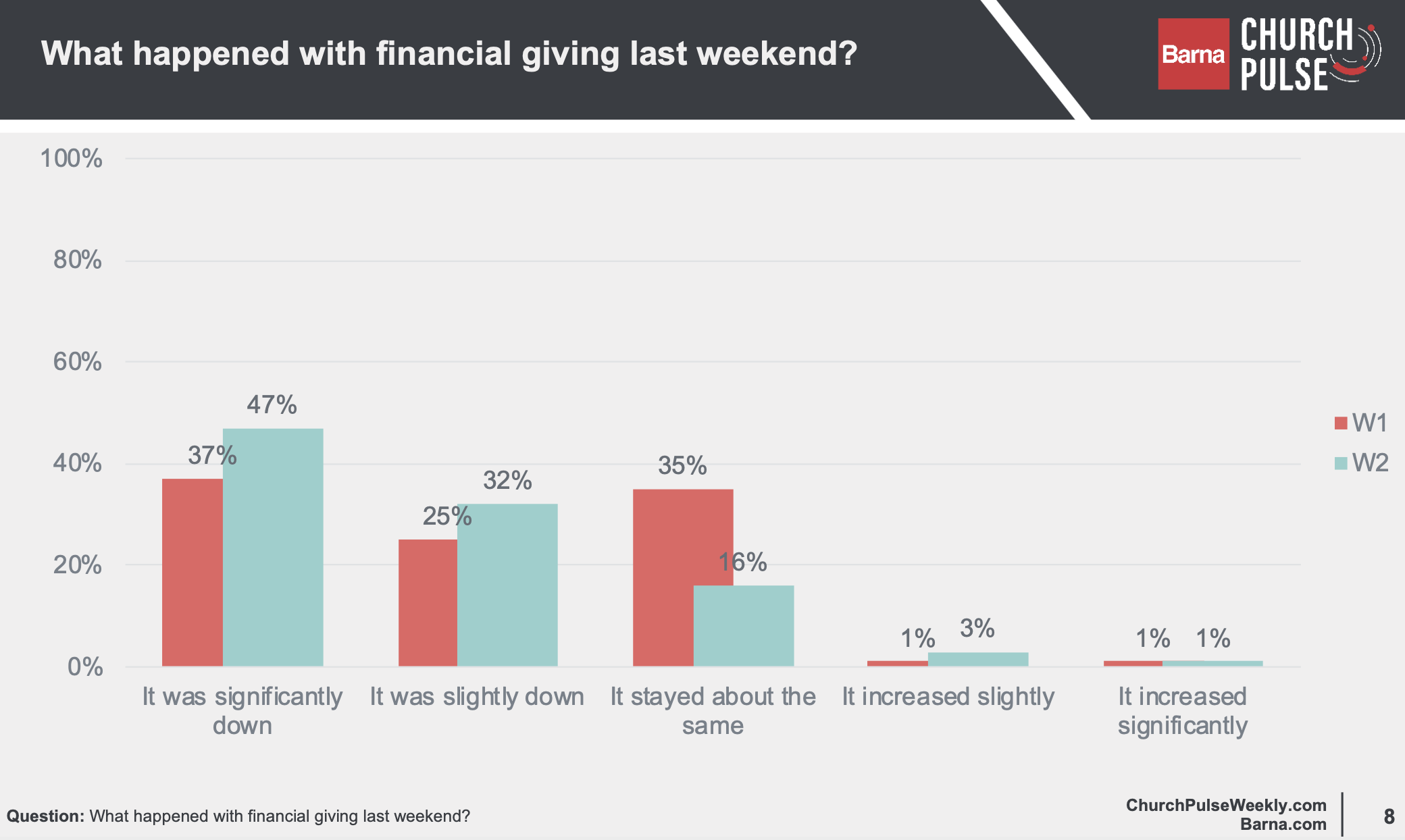

More than three-quarters of pastors surveyed by Barna over the past few days indicated that the coronavirus pandemic had affected the well-being of their church, up from two-thirds during the beginning of the March 20–30 survey window. Half (47%) say giving was “significantly down,” but only one in five (21%) have decided to cut staff hours. The vast majority (71%) say they have not been forced to make staffing changes.

Though they recognize the financial impact as giving levels drop, pastors said their biggest concern is their congregants: how to care for more isolated members from afar and, in worst-case scenarios, how to minister to the sick and dying. (In many places, even chaplains can no longer visit patients.)

What about the people who live alone? The depressed? The sick? Those who have lost loved ones? It feels like just at the time when their congregation really needs pastoral care, they aren’t able to be with them as they typically would.

“I am primarily concerned for the health of our people, particularly those in high risk categories,” said Chris Taylor, teaching elder at Christ Church Bentonville in Arkansas. On his social media feeds, Taylor shares daily clips of driving to congregants’ homes to greet and check in from a distance.

“I am not concerned for us as a body,” he said. “I actually expect us to be strengthened and encouraged by our responses both individually and as a whole.”

Taylor’s outlook reflects what fellow pastors in the Barna survey: 95 percent are confident that their church will endure the pandemic and nearly all say it will not diminish their congregants’ faith, with 42 percent saying it is growing stronger as a result.

Erik Koliser, who pastors the West Campus of Center Point Church in Lexington, Kentucky, brought up the challenge of meeting the “large-scale needs of my church and community,” but said that things have gone better than he expected. “I have to admit I’m quite proud of my church with this so far,” he said on Monday.

Kinnaman at Barna said that without the weekly in-person church gathering, many pastors have had realized how much they counted on seeing people in the pews as a sign of the health of the congregation. “One of the long-lasting impacts of this crisis is that leaders will have to use better tools to stay connected with their people,” he said.

Ed Stetzer, director of the Billy Graham Center, saw similar challenges as more than 1,500 pastors responded to a recent survey around church life amid the COVID-19 outbreak.

“While pastors might have been looking for information or encouragement in the early days of the epidemic, their overwhelming request is for practical advice,” Stetzer wrote on his CT blog, the Exchange. More than half of pastors specifically were looking for resources around ministry outside of Sunday services and traditional face-to-face outreach.