Just as more Americans are becoming religiously unaffiliated (“nones”), there’s another major shift happening on the other side of the religious spectrum. More people today say they are “born again” than at any point in the past three decades.

It almost seems counterintuitive. While significant portions of the country jettison religion, others are increasingly identifying with a more devout expression of the faith. Across segments of Christianity—not just evangelical Protestants—Americans are heeding the scriptural call that “you must be born again” (John 3:7), even when the label has not historically been part of their faith traditions.

For decades, demographers have measured born-again identity. The General Social Survey (GSS), asks respondents, “Would you say you have been ‘born again’ or have had a ‘born again’ experience—that is, a turning point in your life when you committed yourself to Christ?”

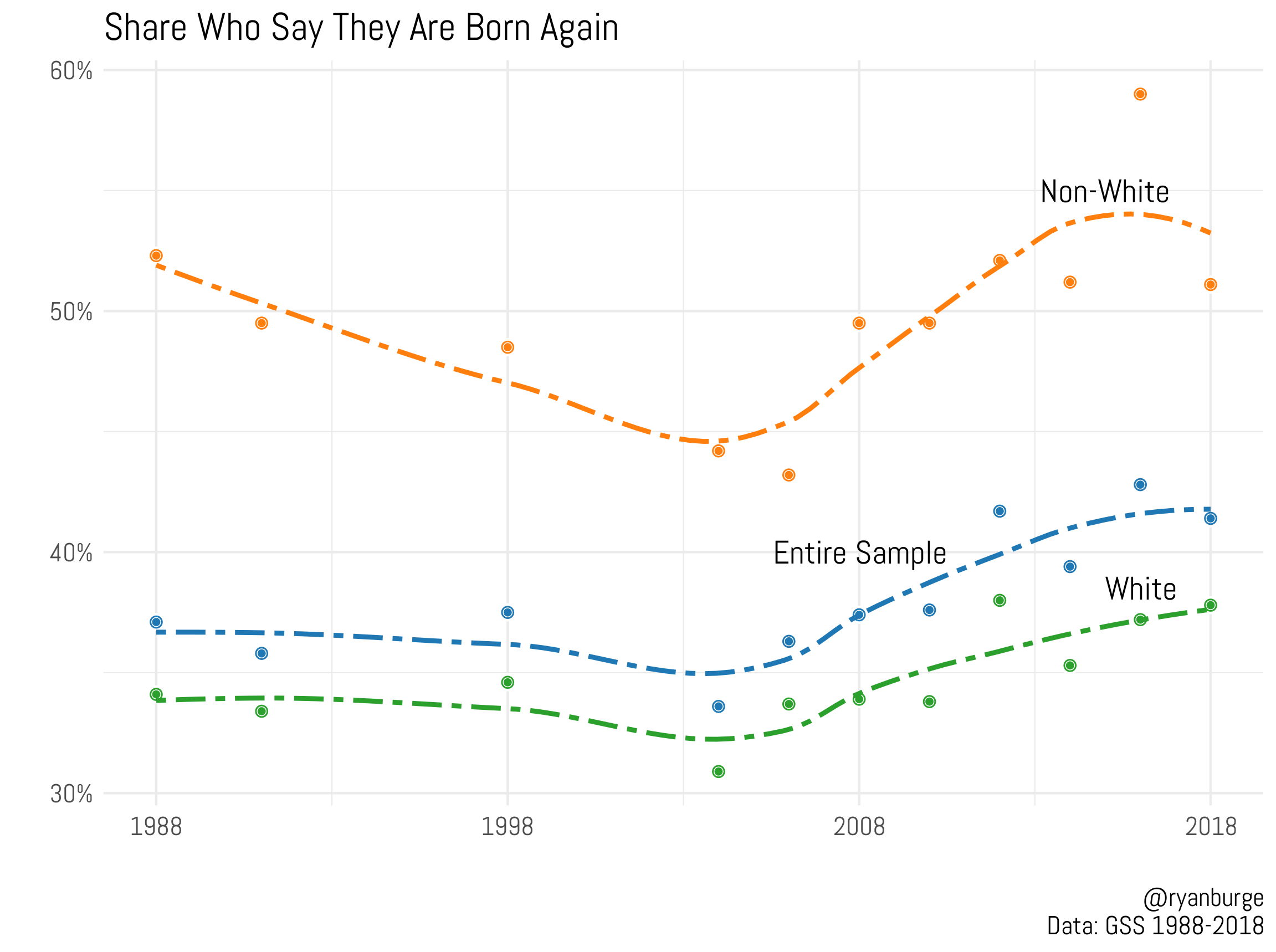

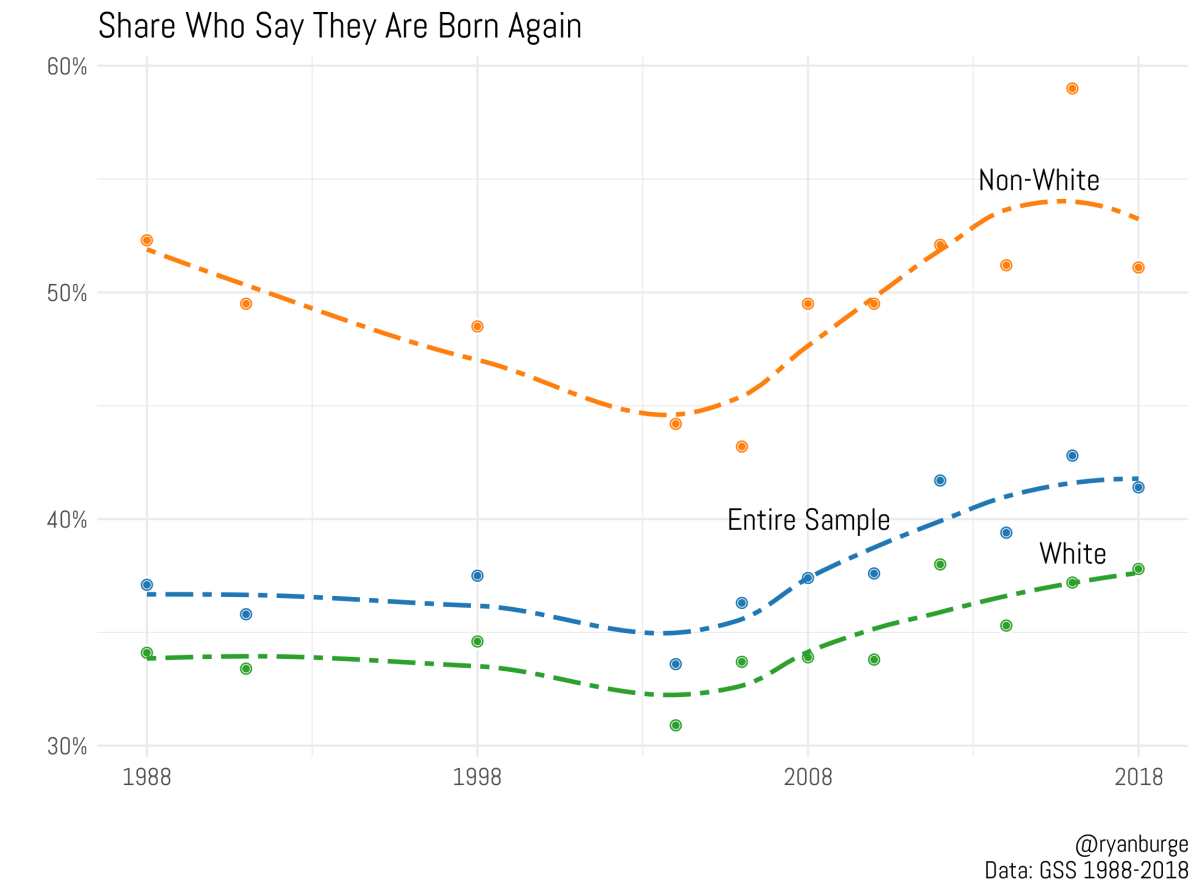

Just over 36 percent of the entire sample said that they were born again in 1988, the first year the question was asked. The question appeared sporadically on the GSS until 2004, when it became a part of every bi-annual survey as the number of affirmative responses began to rise. In the last 14 years, the share of born-again Americans has risen to 41 percent, and much higher (54%) among people of color. Since 2010, at least half of people of color say that they have had a “turning point in their life” when they committed themselves to Christ.

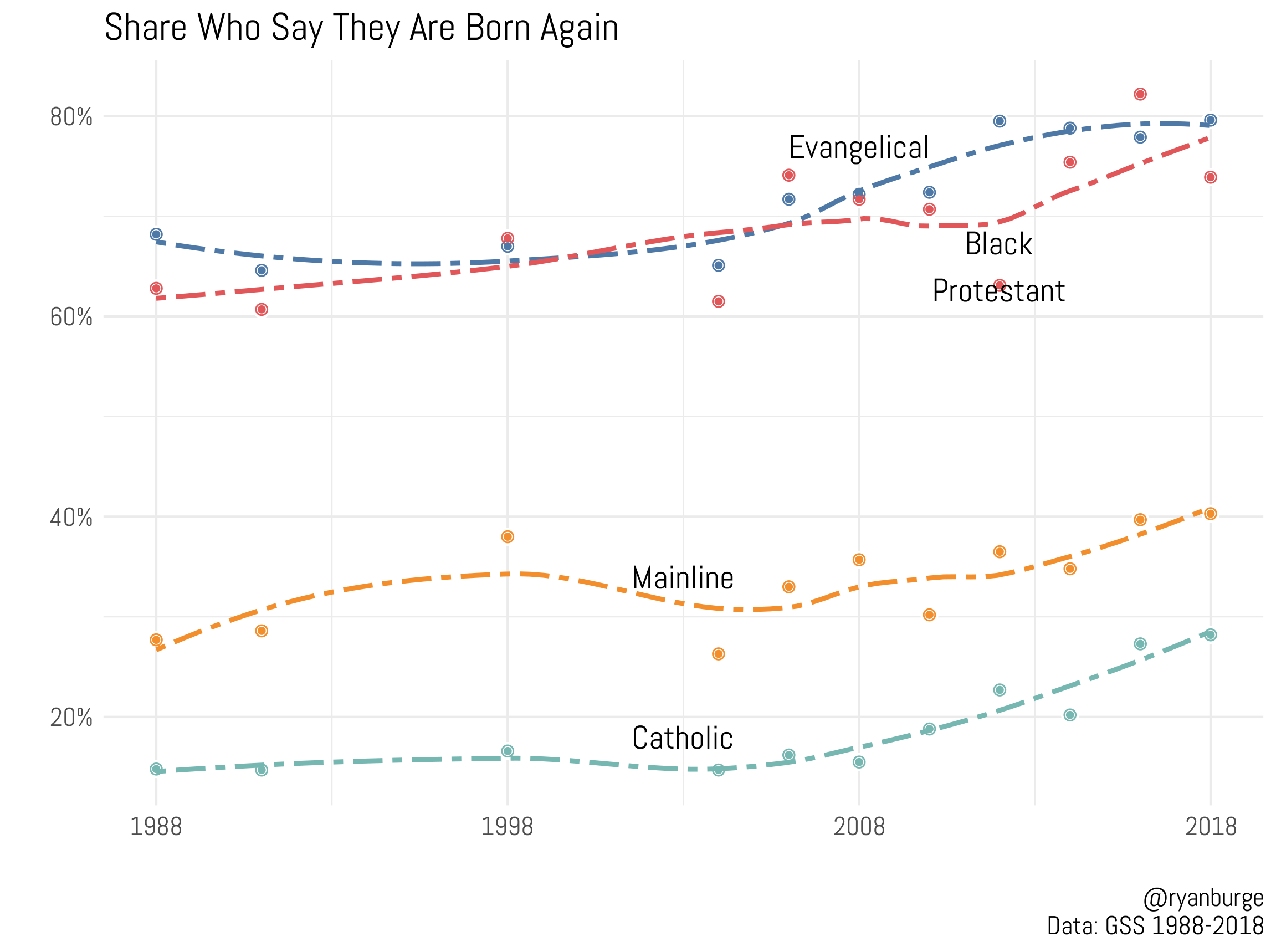

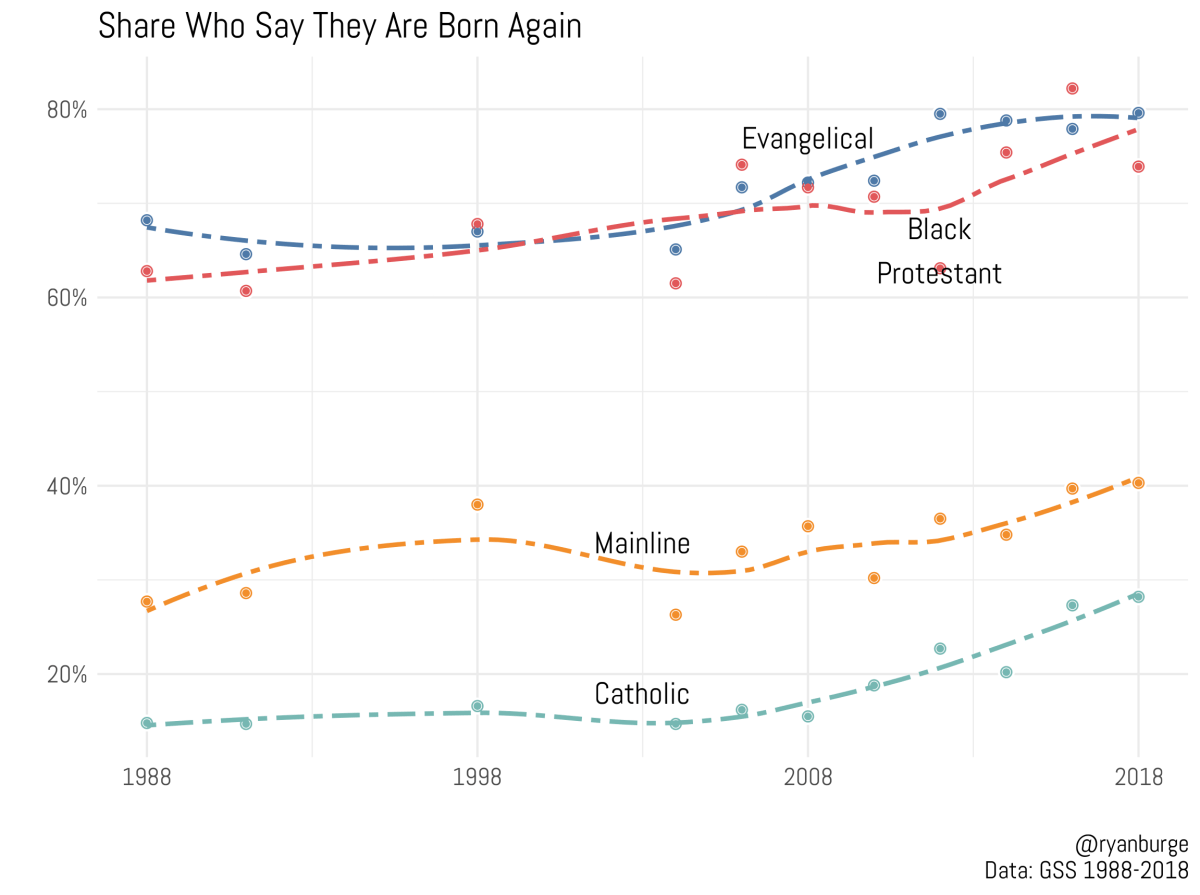

Some might assume the continued rise of born-again Christians reflects the steady portion of evangelical Protestants in America, while mainline Protestants, who are less likely to call themselves born again, have undergone more rapid decline. But actually, across all Christian traditions—even mainline denominations and Catholics—born-again identity is trending up.

Large shares of black Protestants and evangelicals have consistently considered themselves born again, and they’ve grown even more likely to do so over the past 30 years. While just three in five of black Protestants were born again in 1988 (60%), now it’s 80 percent. The increase for evangelicals was 68 percent to 78 percent during the same time period.

The surprise comes with mainline Protestants, who have gone from 28 percent identifying as born again to 40 percent. And the portion of born-again Catholics has doubled (from 14% to 28%). Those increases are especially striking because neither tradition teaches that a born-again conversion is a necessary component of their faith.

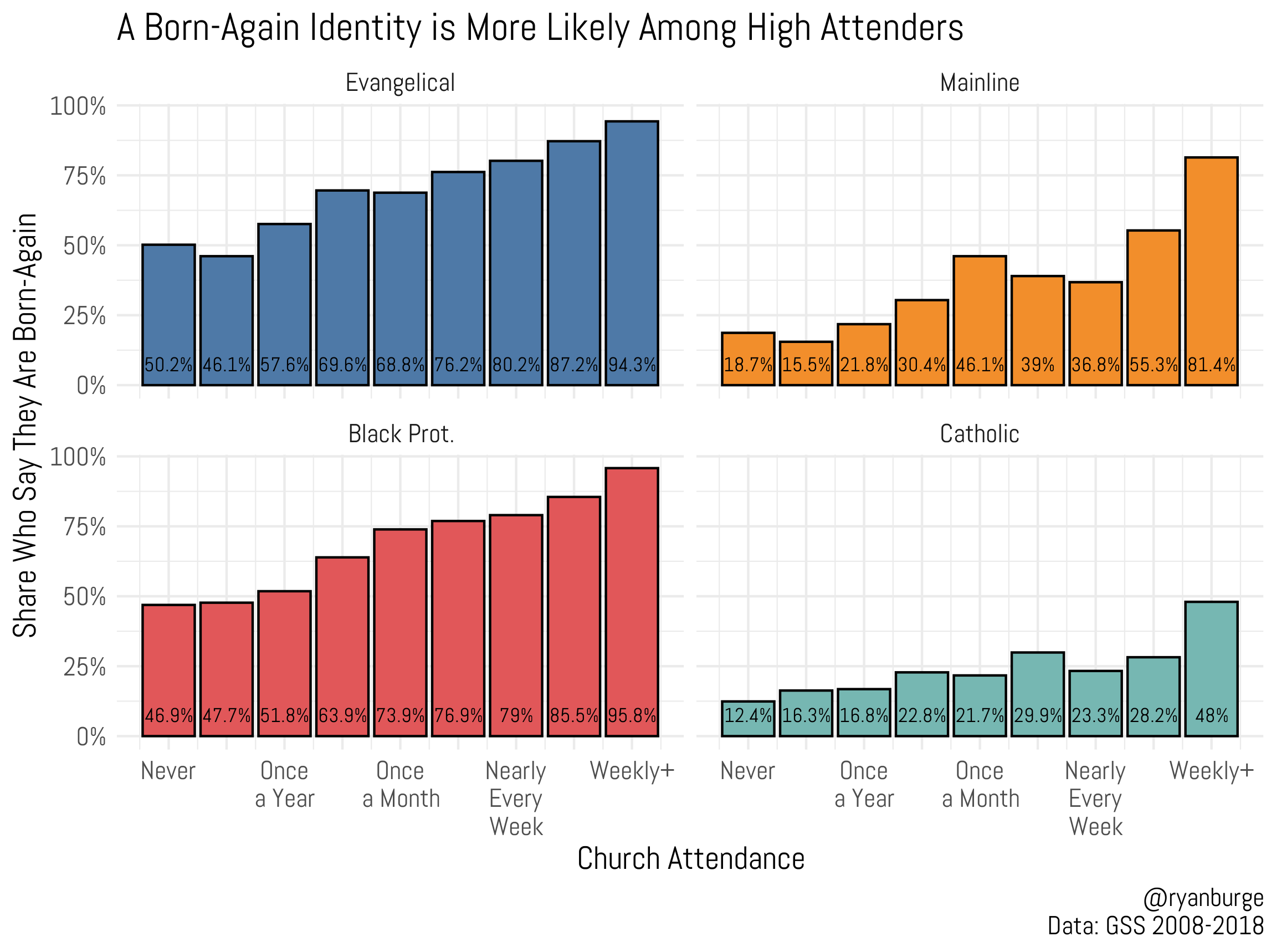

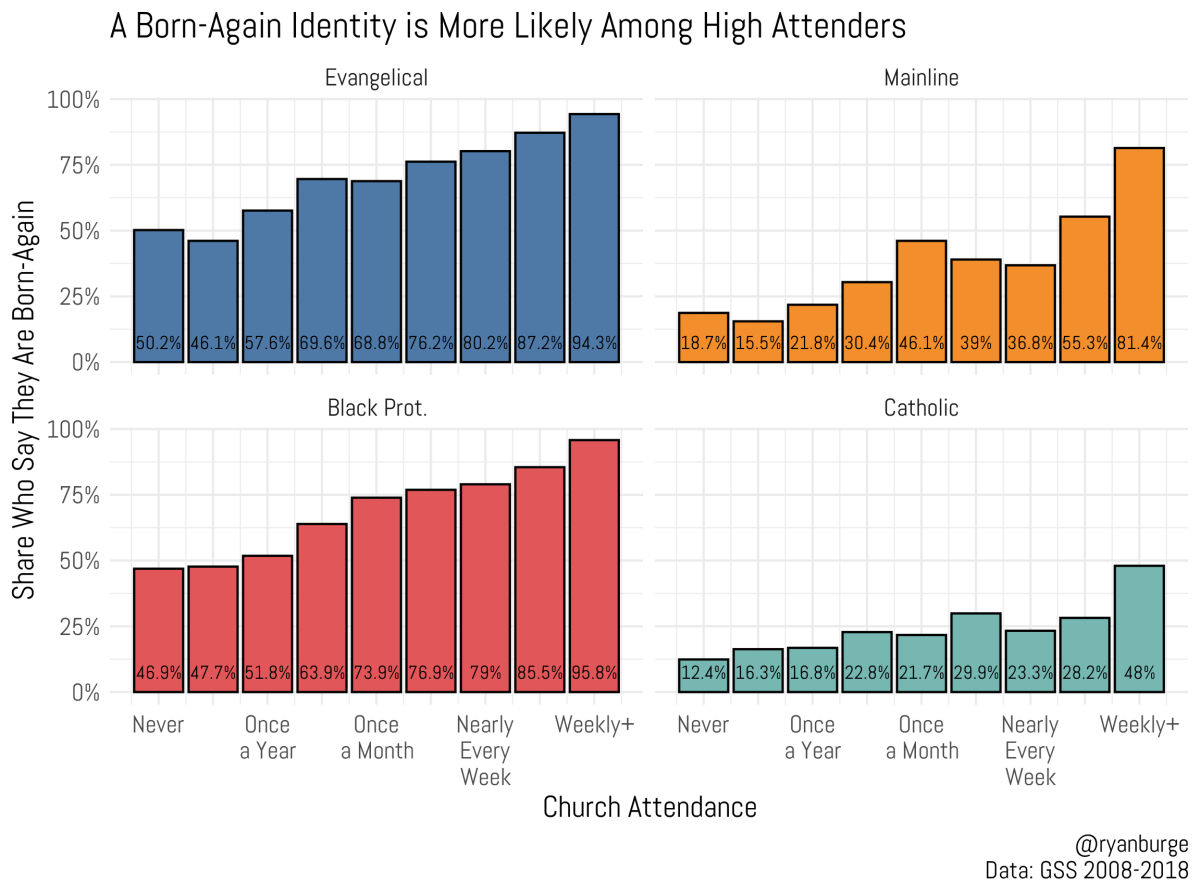

Over the years, being born again may have evolved from being seen as a distinctive for evangelical Protestantism to a way to suggest that they are particularly active in their faith. Across Christian traditions, the more often a person attends church, the more likely they are to say they have had a born-again experience, regardless of their affiliation.

For both evangelicals and black Protestants (on the left of the chart), about half who never or rarely attend indicate that they are born again, but that rises quickly with more frequent church attendance. Approximately 95 percent of evangelicals and black Protestants who attend church multiple times a week say they are born again.

While the total share of mainline Protestants and Catholics who say that they are born again is lower across the spectrum, high attenders are far more likely to express a born-again conversion. Over half of mainline Protestants who attend once a week say that they are born-again, and the data jumps to 81.4 percent among the most active mainliners. Among Catholics, born-again identification is relatively low at almost all attendance levels save for one—nearly half of all Catholics who attend Mass more than once a week say they have had a born-again experience (48%).

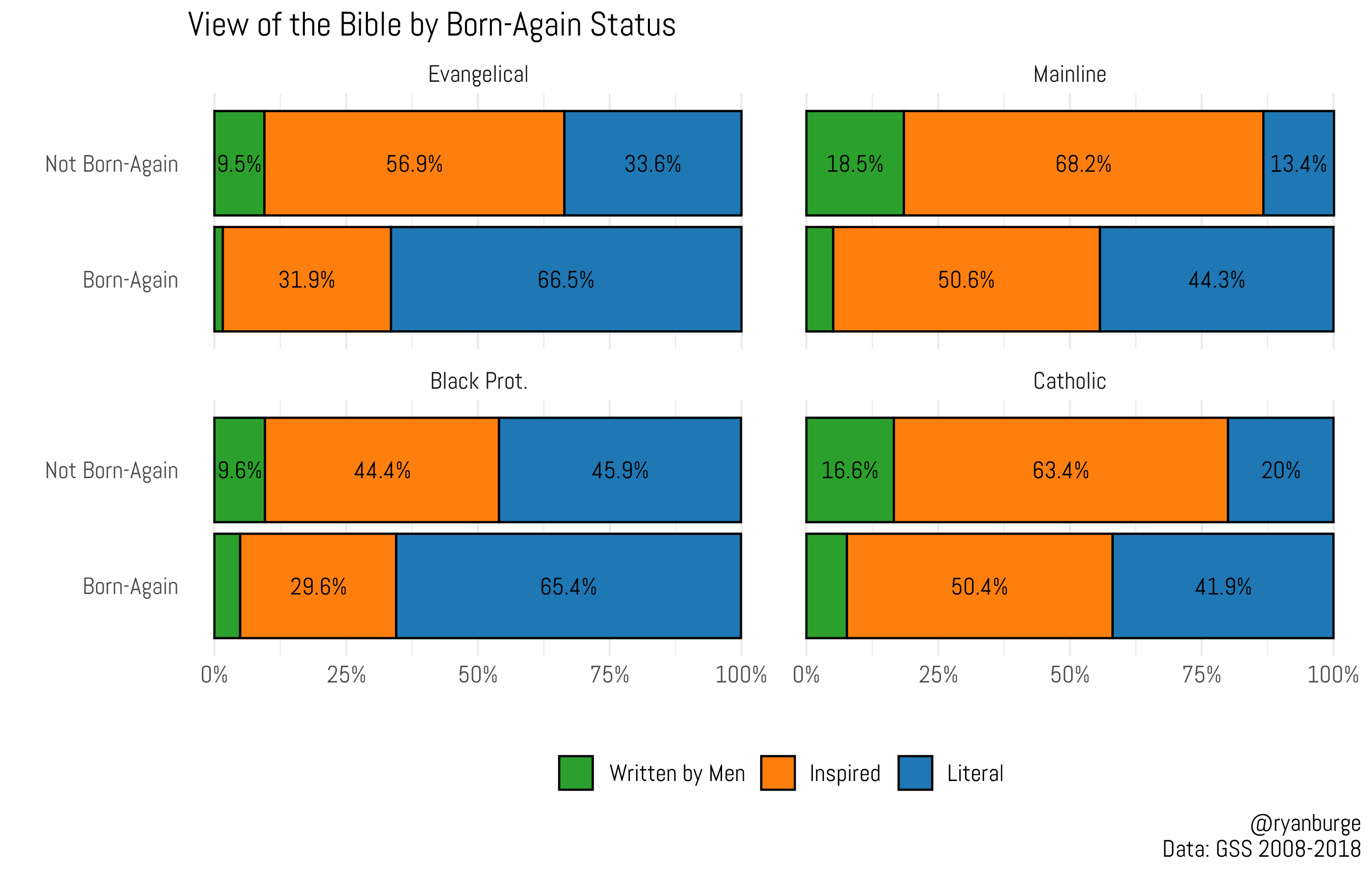

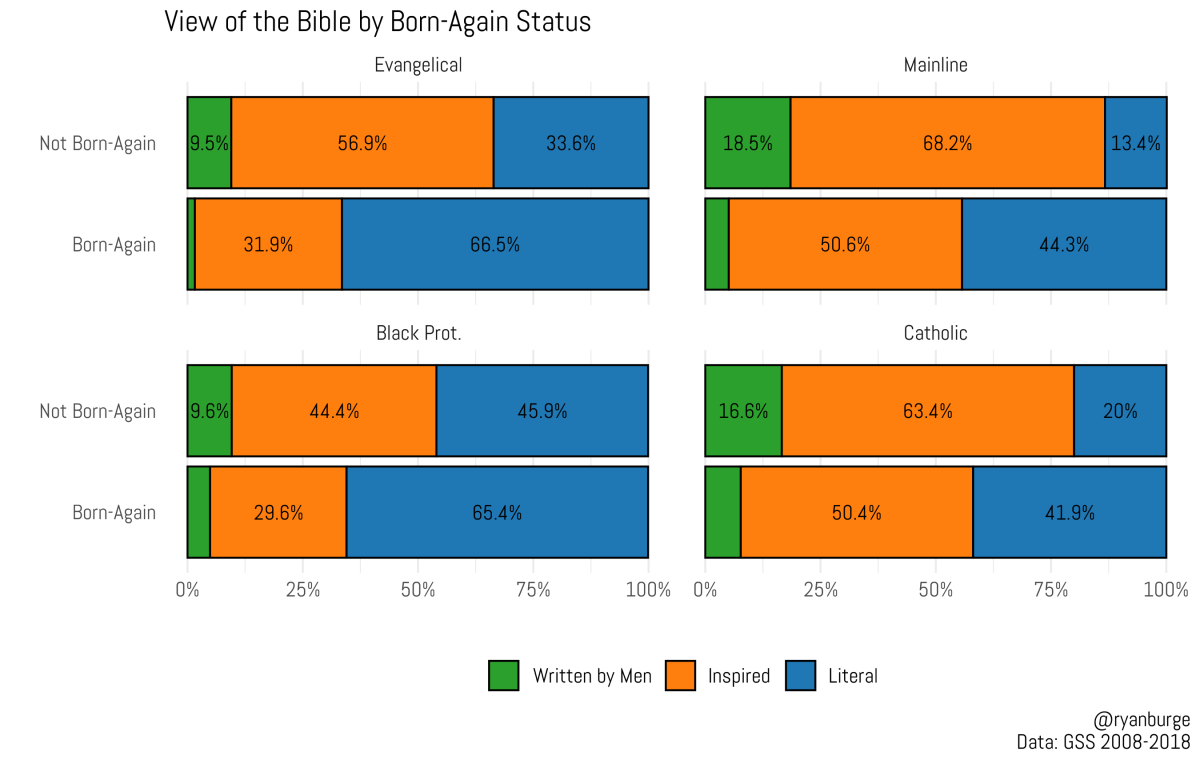

Are born-again mainline Protestants and Catholics more likely to resemble their born-again brothers and sisters in evangelical and black churches when it comes to theological beliefs? Data shows they are much more likely to believe that the Bible is literally true. But there is still a clear divide between the more conservative traditions (black and evangelical Protestants) and the more moderate ones (mainline Protestants and Catholics).

While two thirds of the born-again black and evangelical Protestants believe that the Bible is literally true, the share of born-again Catholics and mainline Protestants who view the Bible the same way falls at under half—41.9 and 44.3 percent respectively. A Catholic who is born-again is twice as likely to believe in a literal Bible than one who does not indicate a born-again experience. For mainline Protestants, the difference is even larger, with a born-again mainline Protestant being three times more likely to believe in a literal Bible.

It would appear that the term “born again” has evolved somewhat among the American public. What used to be seen as a touchstone experience for many evangelicals who went forward at a revival, youth camp, or especially moving Sunday worship service, now seems to mean something more. In essence, the word seems to have been adopted by people of other faith traditions as a way to indicate that they are a devout believer. The data suggests that individuals take the term to mean that faith plays an important role in their life and their religious activity serves more than a social purpose.

Even some Mormons use the born-again label (but the sample size is too small to analyze using GSS data). A couple years ago, the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints ran an ad campaign that implied that their belief system was similar to evangelical Christianity. It was met with a harsh rebuke from Albert Mohler.

It will be interesting to see how frequently evangelical leaders will follow Mohler’s lead and engage in boundary maintenance surrounding their faith tradition in the coming years. For years, the born-again experience has showed up in evangelical statements of faith and definitions like the Bebbington quadrilateral. As more Christians begin to identify as born again, evangelicals who once held this distinctive will have to either form more narrow, exclusive definitions or embrace fellow believers who share the experience.

Ryan P. Burge is an assistant professor of political science at Eastern Illinois University. His research appears on the site Religion in Public, and he tweets at @ryanburge.