Christians have wrestled with a lot of big, new issues related to the body in the past decade—questions about sex, gender, racism, public health measures, end-of-life care, and even artificial intelligence. A growing number of evangelical theologians say the answers lie in the field of theological anthropology, the study of what it means to be human in light of God’s revelation.

“If you asked 10 systematic theologians in the US about the three most important doctrines we’re talking about today, I would be very surprised if you didn’t get all 10 of them saying ‘theological anthropology,’” said Marc Cortez, a theology professor at Wheaton College and the author of ReSourcing Theological Anthropology. “Almost all of the liveliest conversations we’re having in society, in theology, and in the church revolve around differences about what it means to be human and how we flourish as human persons.”

While theological anthropology has “dominated theological discourse for a while,” according to Cortez, the topic has taken on new relevance as a result of cultural shifts. This sense of urgency was visible at the Evangelical Theological Society (ETS) meeting in San Antonio in November, where theological anthropology was the 75th annual gathering’s designated theme. Every seat was taken at a session on Wheaton theology professor Amy Peeler’s new book Women and the Gender of God, with more people standing and sitting knee-to-knee in rows on the floor.

Evangelical theologians are taking topics that “we tend to think of as being more sociological,” Cortez said, and showing they are, in fact, “deeply theological.”

Some say the change is long overdue.

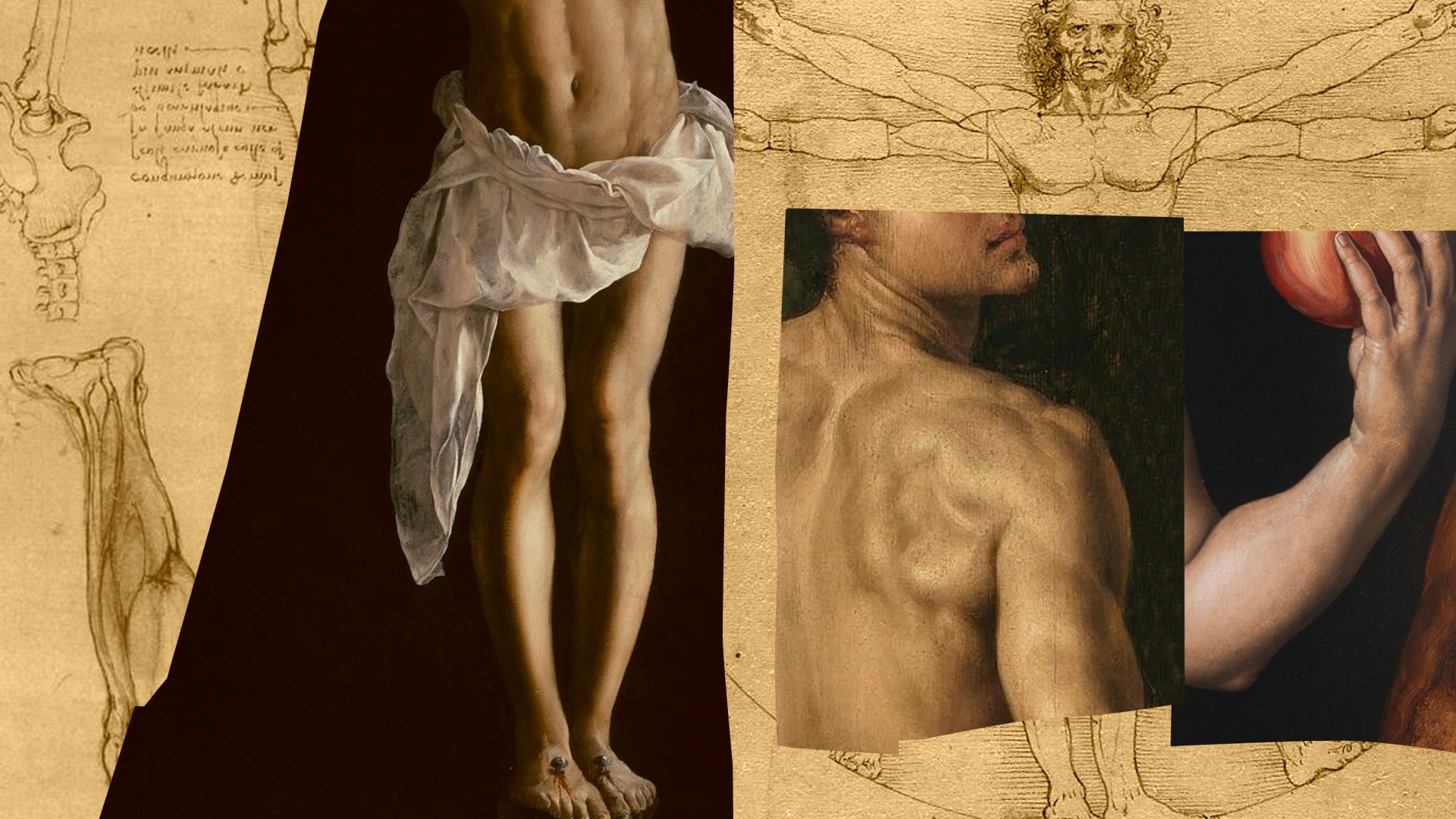

“What I’m really encouraged by is a trend toward paying attention to our bodies and not thinking of ourselves as just brains on a stick,” said Carmen Joy Imes, a Biola University professor and the author of Being God’s Image.

Imes points to the “critical mass” of women in evangelical institutions—including the installment of the first female president of ETS—as one reason for this shift.

“The brain-on-a-stick thing never really worked well for women,” she said. “We have too many bodily reminders of our humanity.”

Some were initially skeptical of “body theology,” since the progressive theologians who first began promoting it decades ago “were taking it in a much more relativistic way—in terms of how the body is fluid and dynamic,” according to Joshua Farris, author of An Introduction to Theological Anthropology and a fellow at the University of Bochum, Germany. “When you reject essentialism [the idea that human nature is fixed or stable with a shared set of core characteristics], I think you open up the door to all sorts of potential ramifications, in terms of how we use our bodies.”

Since evangelical academics began exploring the topic from a biblical and orthodox perspective, it has filtered down to the local-church level. Several books on the topic, including Kelly Kapic’s You’re Only Human and David Zahl’s Low Anthropology, brought theological anthropology to a popular audience. Moral questions are prompting a greater need for resources, and theologians say changes in technology will likely increase the demand for good evangelical work on these issues.

“We need robust theology as a source of knowledge to inform how we understand what it means to be human and how we interact with the rest of the world,” Farris said. “Theologians have something really important to say that philosophers and scientists do not.”

Another reason for the increased interest is that evangelical theology today is more engaged with science. The field has become more interdisciplinary, as theologians interact with contemporary developments in psychology, biology, and neuroscience. Some scholars in theological anthropology are seeking to develop a more robust doctrine of Creation and go around what S. Joshua Swamidass, author of The Genealogical Adam and Eve, calls the “impasse” over issues like the age of the Earth, evolution, and the existence of Adam and Eve.

The theological field is also prompted by the careful consideration of large, secular intellectual trends like the decentering of humanity.

“We’re moving away from an anthropocentric worldview, which is a long overdue corrective,” said Christa McKirland, a theologian at Carey Baptist College. “History shows that humans do not do well when they are in a position to dominate other creatures and creation.”

And yet, she said, “you might call me a ‘speciesist,’ because I think it’s critical not to lose the distinct importance placed on the human race.”

For McKirland, that emphasis is necessary if we accept the biblical idea that humans are created in the image of God and that God became human in the person of Jesus Christ.

She argues that if our understanding of humanness starts with those revelations, then we can “ground human flourishing in something deeper than specific debates about the human person.”

The biblical conception of the human being, evangelical theologians argue, counters secular notions about what we are and what we are for.

Establishing a baseline value and purpose for human life is “one of the goods theological anthropology has to offer the world,” said Daniel Hill, a Baylor University theologian. “The Christian doctrine of Creation pushes back on ‘me as just an acting thing’—that I receive myself in a certain sense before I become it. … And so, my value then isn’t in what I’m doing; it’s actually in this relationship of reception that I have with God.”

While theological anthropology is useful for answering ethical questions, scholars find it also raises other interesting and often complicated questions.

For example, if we Christians affirm that our bodies, with all their particulars, have been given to us by God, then we might reasonably ask which aspects of personhood will persist beyond death and into the new creation. Will our resurrected bodies possess the same traits they do in life—such as our race, gender, sexual orientation, or disabilities?

Some of the most contentious conversations in the field, in fact, revolve around human differences in a fallen world. There are “things we place in the diversity bucket,” said Cortez, and other things that belong in “the brokenness bucket.” It’s not always obvious which is which, though, and scholars debate the standards for discerning what aspects of human difference represent “legitimately different ways of being human in the world” and which are “manifestations of various kinds of brokenness” that Christians should try to alleviate.

These discussions exist “at the juncture of theological anthropology and moral theology,” said Fellipe do Vale, a theology professor at Trinity Evangelical Divinity School. They transcend the basic question of “What does it mean to be human?” and move into “What does it mean to be a good human?” he added.

Yet interest in these more “contingent aspects of being human”—such as race, gender, and disability—is a relatively recent development in evangelical theology.

“For a long time, especially in church history, people wouldn’t talk about them,” do Vale said. “I think these ‘dark-side’ issues only really get dedicated attention when they intrude upon our lives.”

Scholars hope their work will equip local churches and Christian leaders to respond theologically to some of the most pressing problems plaguing the public square today.

“I have never heard a sermon on sexual assault—and it’s in the Bible,” do Vale said. “Where’s the theological guidance for stuff like that that’s gonna impact, statistically speaking, a good chunk of your congregation?”

These and other issues will continue to be discussed by evangelical theologians at annual meetings—as well as in books and papers, seminars and lecture halls. And wherever these scholars gather, greater attention will be paid to the bodies that brought them there.

“We’re embodied, our bodies matter—our bodies are coming with us into the new creation,” Imes said. “That has implications for what we do with our bodies now and how we think about our bodies now.”

Stefani McDade is theology editor at Christianity Today.