On a sunny March afternoon in 2014, I found myself jumping on the L train from Manhattan to Williamsburg to interview a young, urban pastor named Carl Lentz in his luxury waterfront apartment. A trendy evangelical magazine wanted me to profile him. With its nightclub venues and award-winning worship music, his Hillsong church was attracting thousands of diverse young people from around New York City.

Lentz is now featured in an FX documentary, The Secrets of Hillsong, which examines his string of affairs and the embattled church he left behind. The four-episode exposé features a solemn and emotional Lentz sharing that he was sexually abused as a child, admitting to moral failings (from sexual indiscretions to drug abuse), and describing the conflict among Hillsong leadership and staff.

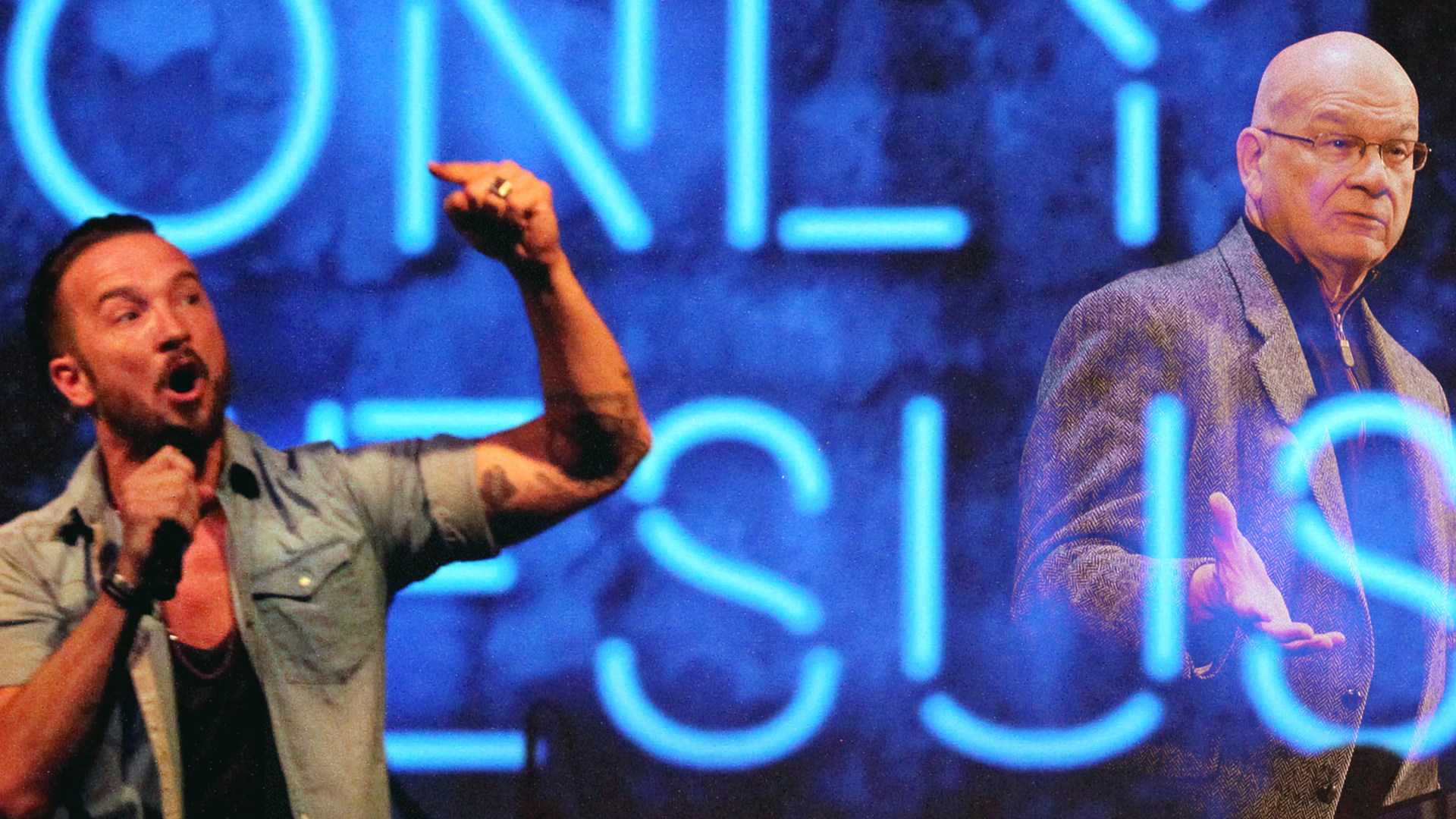

The documentary dropped the same day that another New York City pastor made headlines: Redeemer Presbyterian Church’s founder, Tim Keller, died of cancer on May 19.

In the mid-2000s, both Redeemer and Hillsong drew flocks of spiritually curious New Yorkers, and both brought in around 5,000 attendees weekly across several services. For two years during college, I attended both churches simultaneously. After growing up as a homeschooled pastor’s kid in New England, I moved to New York City for undergrad. But it wasn’t just the star-studded Manhattan sidewalks that grabbed my attention; it was also the churches led by rapidly rising evangelical stars, including Keller and Lentz.

Since then, the evangelical church has been waking up to the pitfalls of platforming and creating celebrity pastors. We’ve watched many of them fall hard into sin after they were groomed for leadership at a young age and given too much power too fast. By contrast, “celebrity” pastors like Tim Keller, who finish their race faithfully if imperfectly, seem anomalous.

But a decade ago, many, like me, didn’t know better. I didn’t understand that my unreflective consumerism and curiosity contributed in part to the creation of celebrity pastors. I hardly understood the theological distinctives between a strongly Presbyterian church and a loosely Pentecostal one. I also didn’t get how leadership structures and accountability systems can make or break a church and its leader.

Despite my naivete, it was hard to miss the stark differences between both churches and their leaders: One formed me. The other entertained me.

Redeemer Presbyterian’s services were marked by hymns, thoughtful and lengthy sermons often delivered by campus pastors rather than Keller (who rotated between campuses), and after-service coffee hour. One campus hosted a jazz-themed worship service on Sunday evenings. I was drawn to the family-friendly environment and the feeling of being biblically and morally challenged each week.

But Hillsong’s vibe was exhilarating. Doors would open minutes before service, catching the attention of passers-by with lines around the block on a Sunday morning. Many described their visit as “an experience.” And it was—the dark room, neon stage lights, thumping worship music, and hyped-up message felt like a concert. Sometimes a small moshpit formed near the stage. During announcements or a meet-and-greet, ushers passed out cups of candy and water. Hillsong successfully drew many people who might not step in the doors of a traditional church: they claimed tens of thousands of converts since its inception.

Even if I knew I wasn’t being theologically fed in the same way as Redeemer, I couldn’t stay away.

Like their churches, the two pastors couldn’t have been more different. Keller started in humble beginnings. He cut his teeth at a small, rural church in Virginia and initially resisted the call to New York. He loved the intellectual side of the faith, acquiring multiple theological degrees, writing dozens of books, and even quitting his first pastorate to become a seminary professor.

Keller had many famous friends but didn’t flaunt those relationships. “Many features of his ministry made him the anti-celebrity pastor , even while he had significant influence and reach,” wrote Katelyn Beaty in the wake of his death. “Keller valued substance over style.”

As several people pointed out after his death, Keller waited until he was in his late 50s to publish his first book. Lentz published a memoir at 39. Keller’s church only ballooned to its current size in the wake of 9/11. Lentz, on the other hand, was poised to be an influential Hillsong leader in his early 20s, as a close friend of the founding family, Brian and Bobbie Houston.

Though he didn’t excel at or love school before Bible college, most of Lentz’s formation came from Hillsong College. And once he became a pastor, Lentz claims, Brian Houston pushed him at a pace he didn’t feel he could handle, at times preaching seven times on a Sunday.

“We can barely handle what we have right now,” Lentz recalls in the documentary. “We don’t have enough leaders; our structure is not strong enough … Before you know it, you’re so far in over your head that it’s a matter of time.”

“The idea of writing about a celebrity pastor having an affair, to be honest, felt pretty pedestrian to me,” Vanity Fair writer Alex French says in the documentary. “There was something else larger that was happening at this church.”

These deeper, foundational issues are only briefly touched on in the film: the platforming of celebrity pastors, the consumer mindset of many attendees, and the emaciated ecclesiology and discipleship of such churches.

The nefarious truth is that we, too, are often responsible for creating celebrity pastors. In college, was I hungry for Scripture and gospel-centered community? Yes. Was I also willing to be emotionally titillated, spiritually distracted and even entertained, and looking for a place to belong? Also, yes.

Regardless of their similarities or differences, I was not looking to become a family member of either church or a caring Christian sister of either pastor, joining in the work of the saints and the partnership in the gospel (Eph. 4:12, Phil. 1:5). I was consuming them, looking to check a box on Sunday mornings at the most entertaining or attractive one-hour experience I could find. Ultimately, I ended my time in New York at a small church plant where I served as a member of that community.

Jesus “triumphed over sin not by taking up power but by serving sacrificially. He ‘won’ through losing everything. This is a complete reversal of the world’s way of thinking, which values power, recognition, wealth, and status,” wrote Keller in his book Center Church. “The gospel, then, creates a new kind of servant community, with people who live out an entirely alternate way of being human.”

Today, Lentz has found a home at Michael Todd’s Transformation Church, a predominately Black nondenominational megachurch in Tulsa, Oklahoma. Back in 2014, Lentz told me that he thought Christians should avoid things that made them vulnerable to sin, and that his priority was to the Great Commission.

“Balance is a funny word,” he said in the interview, “My calling is not to Hillsong New York City, my calling is to serve Jesus and be a good husband and father. If I do that right, the church ends up being fine.”

Kara Bettis Carvalho is an associate editor at Christianity Today.