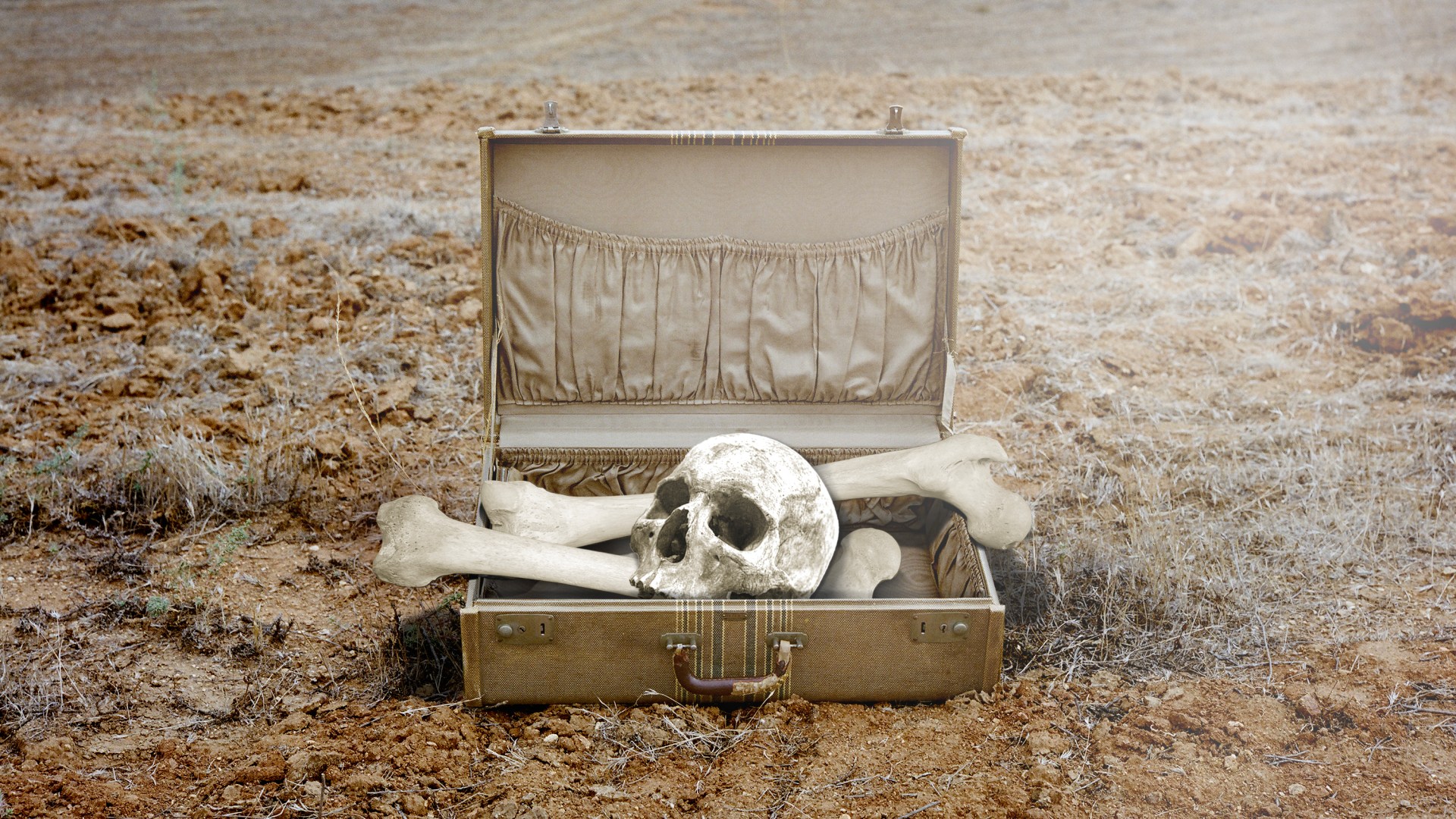

We all know the first words of Genesis: “In the beginning, God created the heavens and the earth.” Far fewer of us can recall the last words of Genesis: “They embalmed him, and he was put in a coffin in Egypt” (50:26, ESV throughout). The first sentence is cosmic in scope; the last, anticlimactic at best. But what if the future of the church has as much to do with the bone box as with the Big Bang?

Today, many Christians refer to Joseph as a model. Some focus on Joseph’s victimhood, trafficked into slavery by his own brothers. Others point to his struggle against temptation, fleeing from the unwanted advances of Potiphar’s wife. Still others focus on his rise to leadership in Egypt, demonstrating how influence can be exerted with integrity. But perhaps the most crucial example we can take from Joseph is not from his life but from his skeleton.

Genesis ends with Joseph’s brothers seeking his forgiveness—a plea that can be viewed as manipulative and self-serving. Nonetheless, Joseph extends mercy, and through him, the line of Israel is delivered from famine.

What’s striking, though, is not what Joseph gives to his brothers but rather what he asks of them: “I am about to die, but God will visit you and bring you up out of this land to the land that he swore to Abraham, to Isaac, and to Jacob. … And you shall carry up my bones from here” (Gen. 50:24–25).

When the Book of Hebrews speaks of Joseph in its description of faith, the only thing it mentions is the bones: “By faith Joseph, at the end of his life, made mention of the exodus of the Israelites and gave directions concerning his bones” (11:22). Why?

This odd request reveals Joseph’s vulnerability. Even with all the technological mastery and political power of Egypt, Joseph knew no pyramid could protect him from death. He also knew he had to rely on his brothers to carry him—the same brothers he once couldn’t trust with his living flesh or even his favorite coat. Yet Joseph knew who he really was—not a prince of Egypt but an heir of Abraham. No matter his fame or wealth, he was a stranger in Egypt. Alongside his vulnerability is hope. Like his ancestors, Joseph could see the promise from afar.

In perhaps the most pivotal moment of the Old Testament, the Exodus, Scripture pauses in its description of the pursuing Egyptian army and the mysterious pillar of fire to tell us, “Moses took the bones of Joseph with him” (Ex. 13:19), just as Joseph had made his brothers swear. And after all the water parting, wilderness wandering, commandment receiving, and Canaanite fighting, the Book of Joshua ends with: “As for the bones of Joseph, which the people of Israel brought up from Egypt, they buried them at Shechem, in the piece of land that Jacob bought” (24:32). Joseph could see not only that the future was bigger than him but also that he belonged there.

The Gospels tell us that Jesus was placed in a borrowed tomb owned by a religious leader named Joseph (Mark 15:43–46). Jesus didn’t have to rely on his brothers to carry him into the land of promise. Instead, after his resurrection, he tells the women, “Go and tell my brothers to go to Galilee, and there they will see me” (Matt. 28:10). All of Jesus’ bones were accounted for, and not one was even broken (John 19:36).

Whether in a local church or in a national movement, how much of the conflict, anger, and despair is really about our fear of mortality or irrelevance? Maybe one reason it’s so hard to hand over the faith to a new generation is that we lack the faith to entrust ourselves to others to carry us, to envision a kingdom bigger than us but to which we too belong. For an Easter people, such should not be.

Maybe the hopefulness we need is to realize that each one of us is headed for the grave—but not for long. We will not carry the kingdom to glory. We will be carried by hands we cannot see. That’s not an anticlimax. That’s a new creation. Even for the most forgotten box of bones, when God says, Let there be life! there is life. Jesus can count all his bones. He can count ours too.

Russell Moore is editor in chief of CT.