About a month before my wedding, I started to have dreams that I was dying. I called my sister who has a master’s degree in counseling and she assured me that it did not mean I had chosen the wrong life partner à la So I Married an Axe Murderer, but that people often dream of death when embarking on a radical life change. The death signifies the ending of one season and the start of something new. My psyche was mourning my singleness. But this death of my old life also brought great hope for what was to come. As I reflect on our current moment, I want us to dream of death again, in the hopes of resurrection. I believe we need to let die our notion of success in the church but especially in our lives.

Etymologically, the word “success” comes from the Latin successus, meaning an advance or ascent. One might visualize a mountain, perhaps utilizing the metaphor from David Brooks’s 2019 book, The Second Mountain, where one achieves personal and professional accolades and accomplishments. Brooks recalls with regret that this frenetic climb up that first mountain deformed him into “a certain sort of person: aloof, invulnerable and uncommunicative … I sidestepped the responsibilities of relationship.” This mountain of success is a lonely place. Victors of its summit include billionaires who indulge in space travel, but also pastors who build up their celebrity platforms, and any of us who define happiness by position, prestige, or power.

We might think that this is not like us: we do not pursue fame and riches. But how often do we make regular decisions and choices that uplift a worldly narrative of success? Do we push our children not to excel but to “get good grades?” Do we accept the promotion at work, even though it will mean a loss of time with our family and friends? Do we censor our small talk or social media profiles to highlight the successful parts of our story? In my conversations with educators, pastors, policy makers, and so forth, I am constantly aware that the evaluation, reputation, or impact report is at the forefront of their thoughts. Success must be tallied and measured, despite our faith that the Lord plants and sows much fruit unseen.

Recently I attended a conference where I spotted a friend and ran to embrace him. He was talking to a woman that I did not know. I said hello, but she stayed seated. I tried to include her in the conversation and find out about her, but it was only when my friend introduced me with an off-handed list of my awards and publications did she stand and pay attention to me. Such a response made me want to retch. If she would not stand to talk to me without my resume, then she should not stand because of any false idea of my merits.

Walker Percy once quipped, “You can get all A’s and still flunk life.” How can we kill off this widespread assumption that success matters? In the Bible, the life of success showcases a dire warning: King Saul, King David, King Solomon. It is the life of the prophets who failed to be heard that God exalts: Isaiah, Jeremiah, Ezekiel. Or, the life of the biggest failure, in the eyes of the world, Jesus Christ, whose ministry led to execution at the hands of those he came to serve. Throughout church tradition, apostles and saints imitate this failure, becoming martyrs, ascetics, forgotten servants of God. Why then do we, in the 21st century, perpetually turn to false ambitions, and how might we let them die?

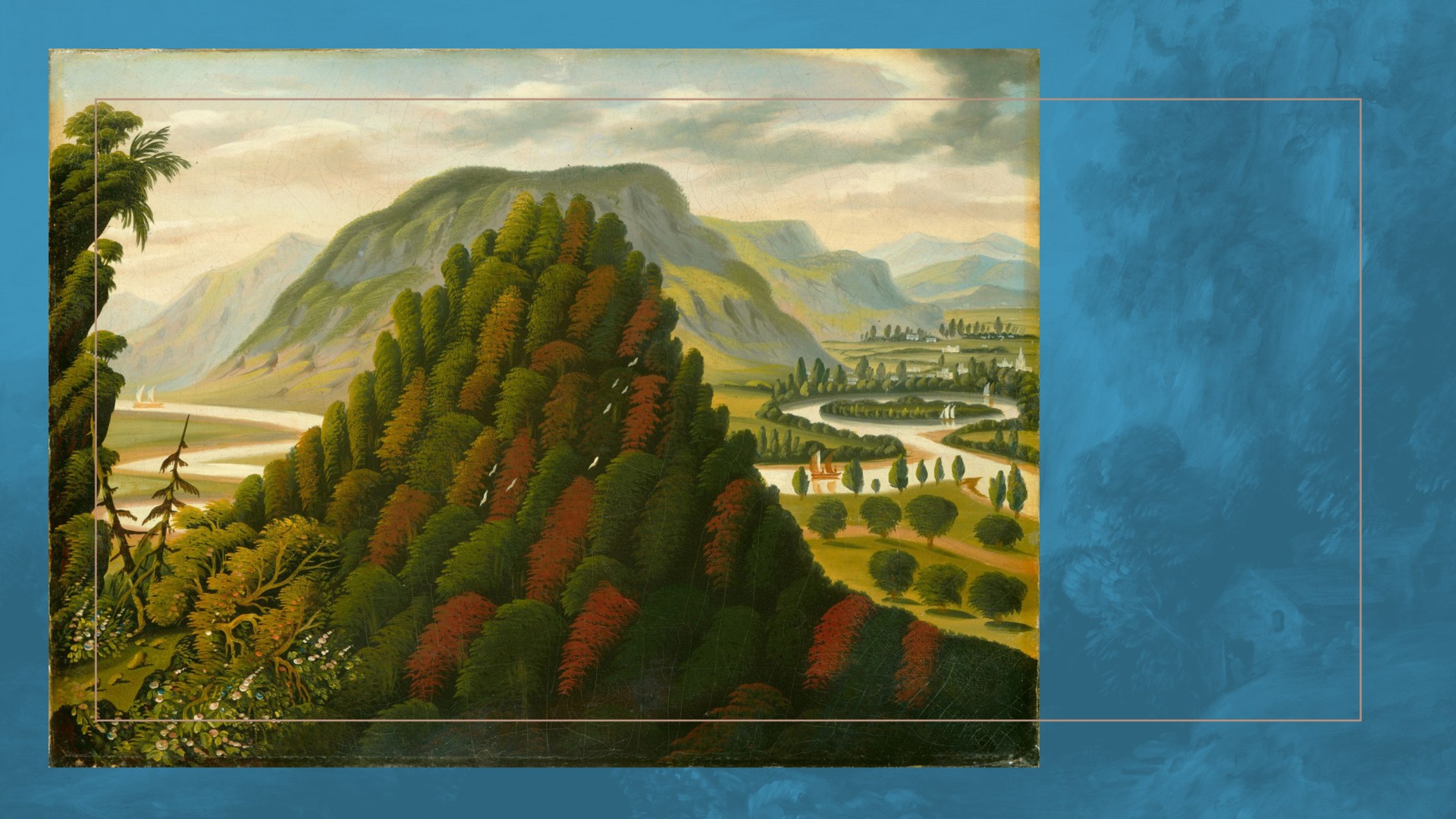

Thomas Gainsborough / National Gallery of Art Open Access

Thomas Gainsborough / National Gallery of Art Open Access“The dead man lay, as dead men always lie, in a specially heavy way”—so begins Leo Tolstoy’s The Death of Ivan Ilych. The title gives the plot away; we already know the story is about our main character’s demise. We should care about Ivan’s death because his life sounds too cannily like our own. As death approaches, Ivan realizes he “had been going downhill” while he imagined the whole time he “was going up”: “I was going up in public opinion, but to the same extent life was ebbing away.” Ivan had been ascending a fake mountain of success. He owned a home that appeared rich with “all the things people of a certain class have in order to resemble other people of that class.” The author hints that Ivan’s successful life is built on a rather flimsy foundation. The happiness that he attains comes in the form of fitting in, seeming to be like others, which means owning what others own.

When Ivan realizes that he will die, he screams in terror, moans, and protests. Ivan does not want to die; he cannot die. Ivan is not ready for death. In the throes of suffering, “the question suddenly occurred to him: ‘What if my whole life has been wrong?’" As Ivan ponders this revelation, he sees that the “scarcely noticeable impulses which he had immediately suppressed, might have been the real thing, and all the rest false. And his professional duties and the whole arrangement of his life and of his family, and all his social and official interests, might all have been false.” Only in facing death does Ivan see all his success as smoke and mirrors, while the real things he ignored.

Ivan is transformed by the hope that, though he lived in pursuit of false ideals, he may die well. He watches his son kiss his hand, and his wife with “undried tears on her nose,” and he empathizes with them. He wants to care for their pain more than his own. He tries to say, “Forgive me,” but merely utters “Forego.” With this new revelation of what matters, Ivan’s fear of death is conquered. The old mountain dissolves into dust. Light replaces death, and joy overcomes pain.

In Brooks’ conversion memoir, there is another mountain to climb, past the smaller peak of success—what Brooks calls the “Second Mountain.” For Brooks, the first mountain offers fleeting happiness, which he contrasts with the joy at the summit of the second mountain:

Happiness comes from accomplishments; joy comes from offering gifts. Happiness fades; we get used to the things that used to make us happy. Joy doesn’t fade. To live with joy is to live with wonder, gratitude and hope. People who are on the second mountain have been transformed.

In Ivan Ilych, we witness this beautiful transformation. Although we have heard these truths before, we continue living as though the first mountain of success is the real summit. But that mountain must die in our eyes. Only the mountains of Sinai, Tabor, and Golgotha are the real places. These mountains must rise up, the holy destinations of our life, which we must ascend. To climb those heights, we need to forego our dreams of success. For these second mountains, as modeled by our beautiful Savior, require not ambition but obedience, transfiguration, and death.

Jessica Hooten Wilson is the inaugural Seaver College Scholar of Liberal Arts at Pepperdine University and Senior Fellow at Trinity Forum. She is the author of several books, most recently The Scandal of Holiness: Renewing Your Imagination in the Company of Literary Saints.

This article is part of New Life Rising which features articles and Bible study sessions reflecting on the meaning of Jesus’ death and resurrection. Learn more about this special issue that can be used during Lent, the Easter season, or any time of year at http://orderct.com/lent.