This piece was adapted from Russell Moore’s newsletter. Subscribe here.

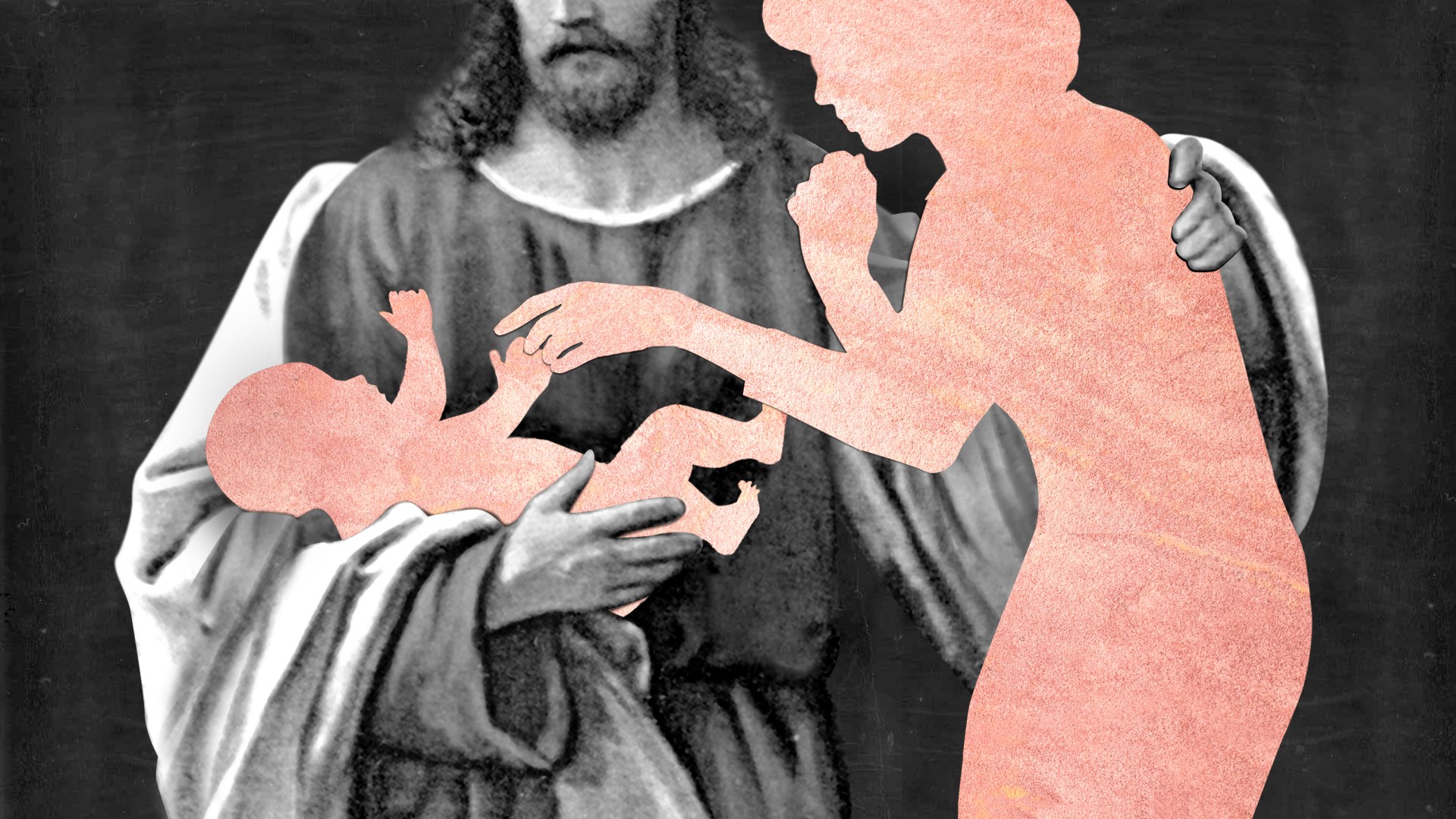

This Sunday marks 50 years since the Supreme Court’s Roe v. Wade decision legalized abortion in the United States.

It’s also the first year in which that date—marked every year by a March for Life in the nation’s capital—falls after Roe was repudiated by the Supreme Court in last summer’s Dobbs v. Jackson Women’s Health Organization decision.

That means the focus this year—for those of us with pro-life commitments—will be invariably fixed on the next 50 years. This may be especially true for those of us who are also evangelical Christians.

And it’s true not just with what we say and do but also with how we say it.

In letters to his son, who is also a pastor, the late Eugene Peterson noticed that our evangelical movements and ministries are often missing “ways and means.” We must be attentive, he argued, to the how as well as to the what.

“When the missional ‘how’ is severed from the worship ‘who and what,’ the missional life no longer is controlled and shaped by Scripture and the Spirit,” he wrote. “And so mission becomes shrill, dependent on constant ‘strategies’ and promotional schemes.”

This is difficult, he wrote, in an American context in which “doing the right thing in the wrong way” is seen as less important than the “success” of whatever project is undertaken.

“But if we are going to live the Jesus life,” he argued, “we simply have to do it the Jesus way—he is, after all, the Way as well as the Truth and Life.”

Peterson was addressing local church ministry, but for those of us who are born-again Christians, the same principles ought to apply in any social reform or human rights movement.

What the world needs from believers is not just effective strategies in ending abortion or even in addressing the underlying causes of an abortion (or euthanasia) culture. The world also needs Christians to embody the Way, the Truth, and the Life—both in where we stand and in how we get there.

The passage Peterson referenced, of course, comes from an interaction between Jesus and his disciples. After reassuring them that he was going away to prepare a place for them and that his Father’s house has many rooms, Jesus said, “You know the way to the place where I am going” (John 14:4).

Jesus’ follower Thomas was immediately perplexed, no doubt thinking that Jesus had given a set of directions, some oracles to be pronounced, or a ritual to be enacted to get them to where he was going. “Lord, we don’t know where you are going,” he said, “so how can we know the way?”

Jesus’ answer here encapsulates, I suppose, all the rest of the Bible. He said, “I am the way and the truth and the life. No one comes to the Father except through me” (v. 6).

Any commitment to protecting innocent human life must tell the truth. We must pay attention to every time the value of human life is eclipsed with distancing language—a way to see at least one of the vulnerable parties involved as an “it” rather than a “you.”

This happens when the woman in desperation becomes a problem to be solved rather than a person with all the mystery that comes with that. Or when her child becomes a “pregnancy” or an “embryo”—an abstraction—rather than a neighbor whose value isn’t dependent on his or her “wantedness” or usefulness to society.

The disintegration of persons and of communities, Wendell Berry wrote, usually starts with a disintegration of words. Telling the truth about the mystery of human life, the image of God, and God’s care for the vulnerable will require a people free from the fear of tribal slogans. Such slogans try to define for us which of our neighbors we should talk about and which ones should go unmentioned.

This also means we recognize the truth that no pro-life vision of any sort can coexist with the sort of sexual anarchy that—intentionally or unintentionally—assigns value to women based on their sexual attractiveness or availability to men. The consumption of pornography is not a separate issue from the sanctity of human life.

That means telling the truth that men and women, mothers and fathers are not just interchangeable and socially constructed fictions. Women are uniquely vulnerable, both in the nurturing of children within the womb and the care of those children afterward.

Likewise, we must tell the truth that a pro-life vision cannot coexist with any kind of racial supremacy, nationalistic idolatry, “bro-culture” misogyny, or culture of cruelty.

As Christians, we stand for life not just in the abstract but, as the apostle John put it, “with actions and in truth” (1 John 3:18). Right now, there are women in our communities who do not know how they will pay rent or even how they can take off enough time from work to give birth, much less to support a child. Right now, within our communities, there are children in poverty who can’t imagine how the future could bring anything other than suffering. We must care not only about life in general but also about each of those individual lives.

Despite all the corruptions and disgraces of American Christianity, evangelicalism, at its best, carries the promise of newness of life.

Wherever a pro-life movement has worked with consistency and sustainability, the message is not just about the injustice and violence of abortion or euthanasia but also the marvel of grace—that Jesus is not shocked or repulsed by people who sin but loves them. So much so that, in him, they can receive cleansed consciences and everlasting life.

Behind all this truth and life is what Eugene Peterson called “the Jesus Way.” It involves refusing to use not only human lives themselves but also our value of human lives as a means to an end—or to use our value of human life to justify acting in ways that degrade human dignity.

When “winning” is the primary objective, one can justify any allegiance, immorality, or idolatry as “necessary” to achieve the goal. Can that sometimes produce political or social “wins”? Yes—in the same way that an embezzling banker can get rich or an adulterous spouse can have sexual pleasure. But what is at the end of all that? What happens to you?

If a person’s character is expendable for “the cause,” whatever the cause is—is that not the very mindset the pro-life movement means to contradict? The life of any person, no matter how addicted or impoverished or elderly or new, is never the price of exchange for anything else, whatever the consequences. The same holds true with a human soul. A Machiavellian pro-life movement would be a victory for a culture of death, no matter how much “winning” it does along the way.

All this matters because we are talking not about a set of issues but about a Person. He does not just point toward the Way; he is the Way. He does not just tell the truth; he is the Truth. He does not just offer life; he is the Life.

For the next 50 years, we need a pro-life commitment to human dignity in vulnerability. Who knows what challenges to such dignity will come next—whether through gene editing, “compassionate” suicide, or maybe even the trans-humanist abandonment of the limits of human nature itself.

We will need to pursue the pro-life cause with consistency—even when that puts us out of whatever tribes to which we think we belong. And we will need to do so with persuasion, recognizing that no legislation or court decision can protect human life if the people themselves do not value it.

But, along with and above all that, we need Jesus.

Russell Moore is editor in chief of Christianity Today and leads its Public Theology Project.