One day in March, Yowati Nthenga, the head of accounting at Nkhoma Mission Hospital, was sitting at his desk wondering where he would get the money to pay the hospital’s roughly 400 employees the overtime and bonus pay they were owed. He had paid salaries, fortunately, but staff counted on that additional “allowance,” and it should have gone out already.

Nthenga’s office is near the gate of the rural, 250-bed hospital, which serves a region of about 460,000 people in central Malawi. On that day, patients arrived on motorbike, on foot, and in minibuses: women in labor, older men with hypertension, a boy with kidney damage. The hospital took care of them, and then Nthenga and the other administrators had to figure out how to pay for it. If patients can’t afford the hospital’s subsidized fees—a consultation costs about 90 cents—Nkhoma’s staff work out a doable amount or find some charitable program to cover the cost. Their policy is to not refuse anyone treatment. But eventually, the care must be paid for somehow.

The hospital is run by the Church of Central Africa Presbyterian, a Malawian denomination. Since it is the only hospital serving Nkhoma’s rural district, the Malawian government helps fund staff salaries. But the county’s health care system relies heavily on foreign funding, as does the mission hospital. And Nthenga has been watching those foreign donations trend downward.

This is happening in mission hospitals across Africa serving rural, poor populations. Giving from Western churches and organizations has declined, while the need for medical care is increasing with population growth. The pandemic worsened that trend, administrators at mission hospitals say, when churches in the United States turned inward to their own needs and the needs of their immediate communities.

As the medical missions world celebrates that mission hospitals are increasingly run by African churches, African doctors, and African administrators, many of those hospitals face a paradox: Weaning them off foreign physicians has long been the dream, but achieving that dream sometimes means losing foreign money.

Nthenga is accustomed to the money stress now: The hospital must find about $40,000 every month from somewhere to cover operating expenses. The staff have a meeting about the books every two weeks to decide which payments are priorities.

Nthenga has been working at Nkhoma for 12 years, and somehow the monthly deficits always work out. Church hospitals historically drew funding from US denominations but now regularly seek help from international organizations like Samaritan’s Purse and, in Nkhoma’s case, African Mission Healthcare.

Still, the pandemic was the toughest two years he and other administrators at Nkhoma Hospital remember. Suppliers started asking for cash up front because the hospital was getting behind in its payments. The hospital has been working on income-generating ideas, but so far it is operating in a deficit.

“The fact is we cannot manage without donors,” Nthenga said.

Frank Dimmock has worked with Nkhoma and in Malawi for years and serves as a liaison between the historically Presbyterian hospital and the Presbyterian Church (USA). He said PCUSA giving to operational expenses at the hospital stagnated during the pandemic, although a few presbyteries gave significantly to the hospital’s COVID-19 response.

Mission hospitals “are all struggling, unless their overseas partner churches are still underwriting them,” Dimmock said. But the number of overseas partners is shrinking. Back in 2011, he surveyed Christian health associations across Africa. Groups from Togo to Malawi reported that foreign giving was down. An association in Chad told Dimmock that Europeans “ask us to focus on the local opportunities of fundraising.”

Since then, Dimmock said, foreign churches aren’t sending as many missionaries—expats who often bring with them visitors and money—as they used to.

Mission hospitals are critical to health care in sub-Saharan Africa, where the majority of the population is rural but health infrastructure is often concentrated in capital cities. Faith-based hospitals like Nkhoma tend to operate in more remote areas. In Malawi, 70 percent of rural health care comes from church clinics and hospitals. Nkhoma is also a teaching hospital, training Malawian nurses, medical students, family medicine doctors, and surgeons.

But providing highly trained staff and hospital infrastructure in remote places is expensive, and the populations mission hospitals are serving don’t have the money to support it. A compilation of household surveys from 14 African nations published in the medical journal The Lancet in 2015 showed that faith-based health facilities had the highest percentage of patients from the lowest economic quintile.

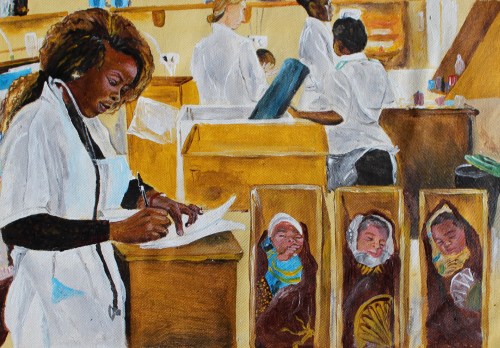

Painting by Eddie Amtonyo

Painting by Eddie AmtonyoAt Nkhoma, the economics of the population the staff served was evident: Some patients came barefoot, and one mother brought in her frail three-month-old baby boy with the copper hair and skin lesions characteristic of malnutrition, as well as her three-year-old who weighed less than a typical one-year-old. The hospital rehabbed the children for 11 days and then discharged them. At a checkup three weeks later, the baby boy whose bones had been showing had gained two pounds and was plump and healthy.

In recent years, financial challenges have compounded to test Nkhoma’s mettle.

During the pandemic, inpatient admissions plummeted 80 percent. According to hospital staff, patients were afraid of getting the coronavirus at the hospital, and because of lockdowns they also didn’t have money for services.

The Malawian kwacha also devalued during the pandemic, making supplies more expensive. Hospital staff were expecting the war in Ukraine to affect their bottom line too, making commodities more difficult to obtain.

The price of drugs, the most expensive line item after salaries, has gone up. There were shortages of magnesium sulfate, which the hospital uses to treat preeclampsia, and diazepam, used to treat seizures. Deciding what drugs to keep on hand is difficult. Some are too expensive to stock for uncommon conditions, and some expire too quickly for a rural hospital on a budget.

“Each time we would go to get quotations for the month or two months, we always get new prices. The prices are not just adding 10 or 20 [percent], but 40, 50 percent,” said Agness Nyanda, the hospital’s administrator. But the patient fees remained the same.

To cut costs, the hospital began limiting the use of its vehicles, which included sometimes canceling non-emergency visits to patients in villages. It tried to reuse protective gowns by dipping them in bleach, but that didn’t work, so it switched to washable fabrics.

In January and February, cyclones added to the hospital’s problems. They disabled one of the four hydroelectric plants that provide the nation’s power, triggering rolling blackouts that have lasted hours a day and continued for months. Heavy rainfall damaged underground cables connected to one of the hospital’s generators, forcing the hospital to rely for several days on an undersized backup generator.

On its ninth day of running, the backup generator quit. The hospital rushed in oxygen cylinders for COVID-19 patients and portable generators to support preemie babies in the neonatal ward. It evacuated an emergency surgery case to another hospital. Women were giving birth under phone flashlights.

Fortunately, no patients died. But Nyanda said repairing the underground cables cost the hospital about $6,000. When the next such emergency comes up, the hospital may have to delay other payments, like staff allowances. While staff generally know they are making sacrifices to work at a rural hospital, where their families might not have as many job or education opportunities, delays on payments add to already-depleted morale.

But then, something new—something encouraging—did happen during the pandemic, in early 2021.

The hospital put out an emergency appeal to local churches, saying that it was in trouble and needed help. The churches responded with the largest amount they had ever given: $13,000. That was meaningful, even if it covered only a small part of the hospital’s monthly costs.

“God has seen us through,” Nyanda said.

On the day Nthenga, the accountant, was trying to figure out what to do about the staff allowances, the hospital got two undesignated donations wired from the United States. One was for $12,000 from a Presbyterian church in Seattle. His problem was solved. If the funds had been designated, he couldn’t have paid the salaries. He ordered a transfer of the donations directly to the hospital’s bank account, which added up to enough money for the staff allowances to go out.

“So the question is, what will happen next month!” Nthenga said with a hearty laugh. “By God’s grace we are moving, and the years are going by. I get amused and amazed sometimes; what has made us go past 2019? What has made us go past 2020? 2021, 2022? God’s grace is upon us, but we are also doing our part.”

Emily Belz is news reporter at Christianity Today. She is based in New York.