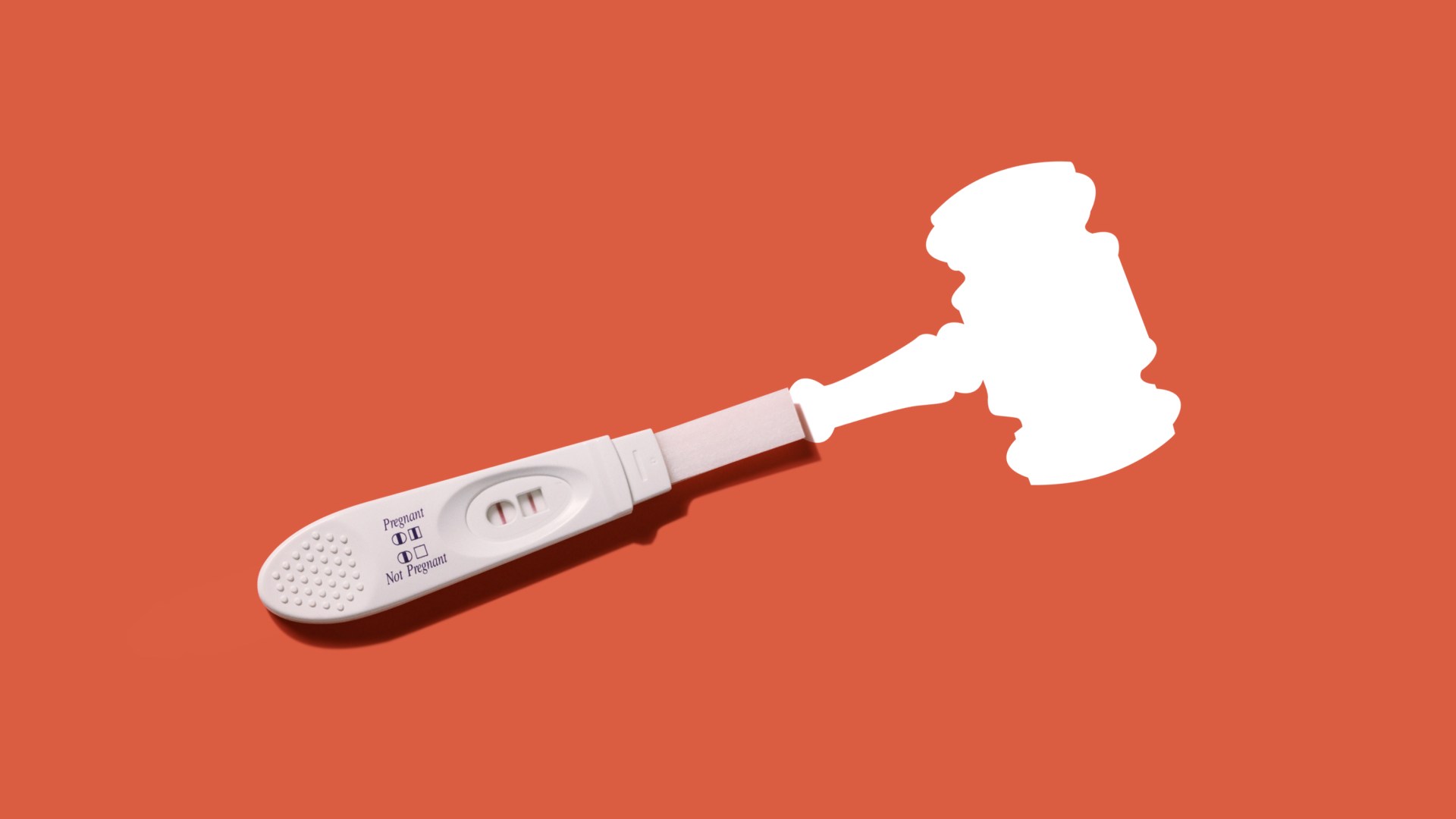

In the recent breathtaking development from the US Supreme Court, a leaked draft opinion for the Dobbs v. Jackson Women’s Health Organization case indicated that abortion rights would be reversed.

In the fallout, headlines appeared warning women that if the rulings Roe v. Wade and Planned Parenthood v. Casey are overturned, their access to healthcare would be compromised—not just for abortion, but also their treatments for ectopic pregnancies and miscarriages.

While news reports declare “Overturning Roe v. Wade Will Make It Harder to Treat Miscarriage” and “Overturning Roe Could Make Ectopic Pregnancies Extremely Dangerous,” some pro-life advocates are saying there should be no cause for concern—and that to say otherwise is to play into the agenda of abortion advocates.

As a Christian woman who’s been involved in the pro-life movement for well over a decade, both professionally and personally, it deeply matters to me that the pro-life movement always provides the utmost care and concern for both a woman and her preborn child.

I worked on Capitol Hill for the sponsor of much of the pro-life legislation, like the “Pain-Capable Unborn Child Protection Act” and the “Born-Alive Abortion Survivors Protection Act,” and I’ve volunteered with local pregnancy centers, advocated for children in foster care, and now my husband and I are in the middle of an adoption.

Statistics show that approximately 10–20 percent of pregnancies end in miscarriage, which is when the embryo or fetus does not survive by 20 weeks gestation. In an ectopic pregnancy—just 1–2 percent of the time—the embryo improperly implants outside the uterus, posing a significant risk to the mother’s life. They are the greatest causes of maternal mortality in the first trimester for pregnancies in North America.

A ruptured ectopic pregnancy in the first trimester accounts for 10–15 percent of all maternal deaths. These are not considered viable pregnancies, and doctors must act quickly to save the life of the mother. Even if a mother was willing to sacrifice her life, the baby would still die because it is not implanted in a place where it can grow.

The medical options used to treat some miscarriages, as well as some ectopic pregnancies, can be the same or similar to those prescribed for an abortion. This makes it imperative to carefully define our terms. Making things even more confusing: Miscarriage can be labeled with medical terminology as a “spontaneous” or “missed” abortion, although it is not an abortion in the most common use of the word.

Included among those procedures are a dilation and curettage (in which the fetus is removed through surgery) or dilation and evacuation (in which a probe-guided vacuum removes fetal tissue from the uterus). Medications called mifepristone and misoprostol can also be used in the case of miscarriage and are the most popular forms of abortifacient in the US.

Miscarriages and ectopic pregnancies can be extremely traumatic experiences, physically, mentally, and emotionally—but it’s important to point out that they are emphatically different from elective abortions, and any confusion of language can further traumatize many women.

Treating a miscarriage or an ectopic pregnancy is not the same as the intentional abortion of a preborn life. In these kinds of tragic and dangerous cases, protecting the life of the mother is the ethical and moral mandate.

Most people who worry about women’s access to healthcare after the Dobbs ruling are usually not referring to these special cases. They are advocating that access to abortion—for any reason, at any time—should not be limited. However, as pro-life Christians, we should be aware of the legal nuances and potential pitfalls in the policymaking process instead of assuming it will always be a simple black-and-white issue.

“My concern about many who come from deeply within the pro-life movement is that concerns like this can sometimes be dismissed out of hand as ‘abortion rights propaganda,’” said Kelly Rosati, child advocate and former VP of advocacy for children at Focus on the Family. “And, that can happen, for example when abortion rights’ proponents refuse to admit that it’s even possible to have statutes drafted to properly and adequately account for these concerns.”

“I think it’s really important to avoid both extremes,” she says.

Amid the misinformation online, which can provoke fear-inducing conversations, it’s important to parse out the truth. To do so, we must first understand why the Dobbs case is so significant, and why this unique case could actually reverse the Roe ruling.

National Precedent

The Mississippi Gestational Act—the law the Supreme Court is examining in the Dobbs v. Jackson Women’s Health Organization case—defines abortion as:

the act of using, prescribing, or administering any instrument, substance, device or other means with the purpose to terminate a pregnancy with knowledge that termination will, with reasonable likelihood, cause the death of an unborn child.

The law clarifies that it’s not considered an abortion “if the act is performed with the purpose of removing a dead unborn child caused by spontaneous abortion or removing an ectopic pregnancy.”

There is no current policy in place prohibiting the treatment of miscarriage or ectopic pregnancies, and many laws similarly exclude such circumstances from the definition of abortion. And yet several proposed bills have raised alarm for some women that access to treatment for miscarriage or ectopic pregnancy could be inadvertently impacted.

For instance, an abortion restriction bill was initially proposed in Ohio in 2019 advocating for the reimplantation of ectopic pregnancies—invoking the use of a nonexistent and medically impossible procedure—but was struck down in hearings. The Ohio lawmaker behind the bill later admitted that he had not researched ectopic pregnancies beforehand.

Another proposed abortion restriction bill in Ohio, currently in the process of hearings, would provide an exception for life-threatening cases. However, some say the bill must be amended further, arguing that the rules outlining these exceptions have too many complicated stipulations—including the requirement to have immediate access to a NICU, which could put a women’s life in jeopardy if she has an ectopic pregnancy and doesn't live close to a facility.

In Missouri, the House Committee recently amended a bill banning the sale or importation of abortion-inducing medications—which previously had no exceptions for ectopic pregnancies. In Texas, some physicians are already claiming to encounter difficulty in obtaining medications prescribed for women whose baby dies early on to help their bodies release the pregnancy.

It’s important to remember that introducing a bill is not the same as a state level bill becoming law. Still, state legislators should ensure that any proposed legal policy would allow for life-threatening exceptions, including speedy care for miscarriage and ectopic pregnancies.

State legislators who rightly desire to pass laws that protect life should be careful and precise in the language they use to ensure that doctors are not hindered in their treatment of women with miscarriages or ectopic pregnancies. Any proposed policy should be clear that no woman facing these pregnancy complications will encounter any delay or difficulty in accessing care.

Thousands of pro-life hospitals and medical clinics do not provide abortions but routinely treat women with miscarriage and ectopic pregnancies. And amid these new fears, we must ensure that the same medical options will available to these women, as they have been for decades.

Indeed, we must advocate for all women—especially those facing the greatest risk in our society—to have access to vital maternal care that is both efficient and affordable.

Chelsea Sobolik serves as the Director of Public Policy with the Ethics and Religious Liberty Commission. She is the author of Longing for Motherhood–Holding On to Hope in the Midst of Childlessness, and a forthcoming book on women and work.

Speaking Out is Christianity Today’s guest opinion column and (unlike an editorial) does not necessarily represent the opinion of the publication.