In September 2017, Category 5 Hurricane Irma struck Barbuda, forcing residents to evacuate to the neighboring island of Antigua and rendering Barbuda uninhabitable. Only ten days later, another hurricane, Maria, passed just south of Antigua, battering it with wind and rain on its way to also becoming a Category 5 storm.

Antigua and Barbuda’s director of the Department of Environment, Ambassador Diann Black-Layne, told The New York Times that the carbon output of developed nations is a significant cause of the intense storms. But she said the island nation is too small to improve the problem on its own. Instead, she offered a surprising action plan.

Black-Layne told reporter Michael Barbaro, “We pray. We are God-fearing people, and we believe in forgiveness, and we believe in praying. And we believe that God will intercede on our behalf. I’m telling you; prayer is powerful.”

The Lord does promise to hear her cries (Ex. 22:21–24). And if God hears those cries, so should his people. Too many Christians (and non-Christians) think about climate change as primarily a political or an economic issue. But it is also a spiritual issue that requires a biblical approach.

The Bible actually has a lot to say about human-caused climate change. The Old Testament, in particular, chronicles God’s efforts to order a society’s energies to his glory and documents that society’s failure to abide by that order.

Biblical teaching should lead Christians to anticipate human-caused climate change. It should incline them to respect the evidence of today’s climate crisis, even if they come to differing conclusions about how to interpret that evidence. And perhaps most importantly, the Bible teaches shows that climate crises often have a reformational purpose.

Land and law

A life-giving climate comes of God’s goodness. On this, Christians of all climate-change persuasions agree. Some even cite as a prima facie argument that a good God would never allow the climate to go bad. But weather is clearly vulnerable to human activity. This lesson appears as early as the Garden of Eden.

Genesis introduces Eden as a place gifted with a favorable climate (Gen. 2:5–6) and also introduces humankind’s relationship with God as stewards of his world (2:15–19). Human sin causes everything we steward to suffer—including God’s gift of the climate (Gen. 3:17–19; Rom. 8:19–22).

These themes continue in the Exodus narrative. God delivered Israel from Egypt to another land identified right away by its good climate (Deut. 11:9–12). For Canaan’s good weather to continue, however, the people had to follow God’s ways. Deuteronomy says, “So if you faithfully obey the commands I am giving you today—to love the Lord your God and to serve him with all your heart and with all your soul—then I will send rain on your land in its season, both autumn and spring rains, so that you may gather in your grain, new wine and olive oil” (vv. 13–14).

Among the laws God gave Israel, he included land- and climate-management rules to guide their climate stewardship. Christians can still glean wisdom from those laws.

One of the most striking “environmental regulations” in the Old Testament is the Sabbath year land-fallow law (Ex. 23:10–11). Without modern fertilizer, farmers at the time—and many farmers still today—had to replenish soil nutrients by crop rotation or by letting fields go uncultivated for a season. Failing to do so leads to soil depletion, lack of plant growth, loss of moisture retention, and trouble with evaporation and rainfall.

Ancient Israelites were to leave their fields fallow every seventh year. Leviticus warns that ignoring this principle would lead to this hardened soil and loss of rainfall. “But if you will not listen to me and carry out all these commands … I will break down your stubborn pride and make the sky above you like iron and the ground beneath you like bronze. … All the time that it lies desolate, the land will have the rest it did not have during the sabbaths you lived in it” (Lev. 26:14–35).

Yes, the regulation had societal and spiritual functions, carving out a recurring occasion for physical rest and for trust in God’s generous provision. But it also established a relationship between soil depletion and rainfall loss that modern science recognizes. Its presence in Israel’s law indicates an understanding that human activity can directly impact the climate and that God expects his people to moderate their activity accordingly. The fallowing law did not block land use altogether, but it did constrain its economic production to protect the environment.

Biblical Israel lacked the scientific sophistication to explore climate mechanics beyond such basic insights. Even so, Israel was taught to regard the climate as requiring stewardship. Further land and climate guidance was built into Israel’s festival calendar.

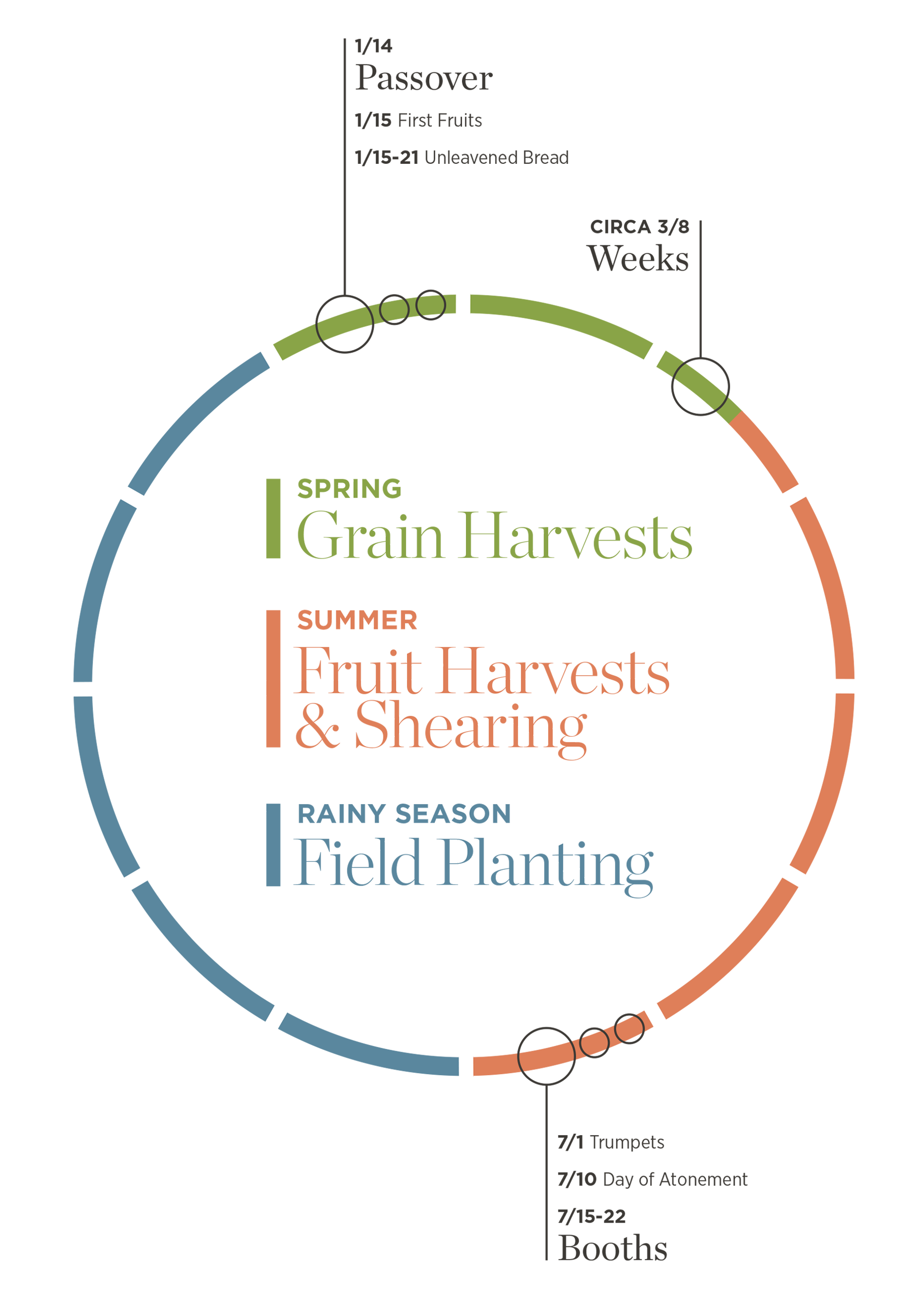

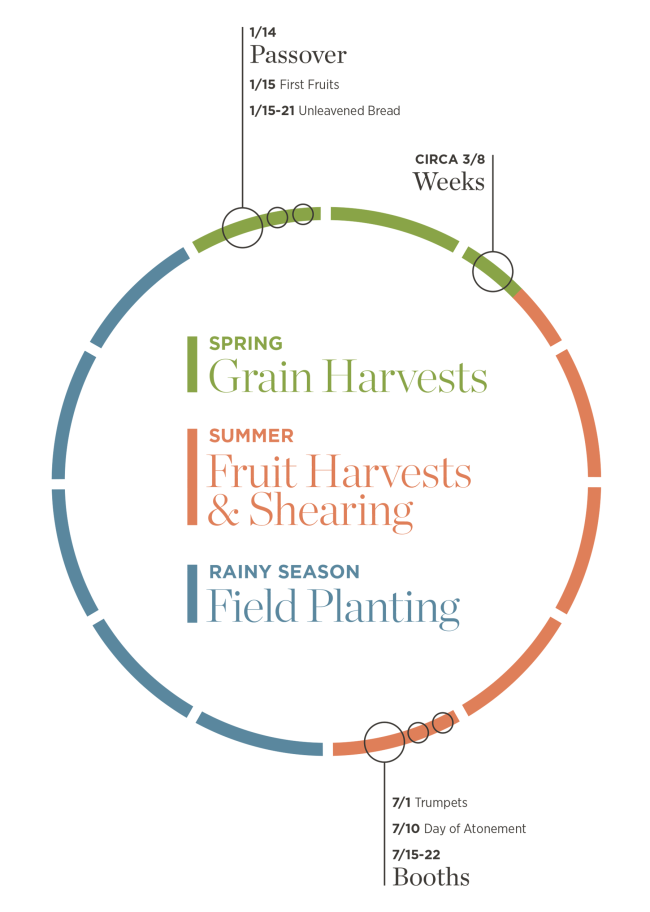

Three pilgrimage feasts formed the backbone of Israel’s calendar, each requiring a national assembly in Jerusalem. Their timing and ceremonies guided Israel’s stewardship of the land in keeping with its seasons.

The first was Passover. It marked the transition from the rainy season to spring, when the barley harvest was ready. The Feast of Weeks occurred seven weeks later, the time when spring gave way to summer and the wheat harvest was ready. The final pilgrimage, the Feast of Booths, marked the end of summer, when summer fruits were ready the next rainy season was at hand.

These festivals taught Israel to labor and worship responsively to the seasons. Israel also learned how to use the wealth their harvests produced. Households brought tithes and other offerings from each seasonal harvest to the assemblies (Deut. 16:1–17). Some of the tithes were eaten during the festivals. But much of this income was placed in storehouses to support ongoing Levitical welfare for the vulnerable (14:28–29).

Through this seasonal calendar, Israel was taught to steward the climate by ensuring the harvested wealth blessed all the land’s inhabitants, including the landless and vulnerable. Israel was told to expect their good climate to continue as long as they observed these laws.

“If you fully obey the Lord your God and carefully follow all his commands I give you today … The Lord will open the heavens, the storehouse of his bounty, to send rain on your land in season and to bless all the work of your hands. … However, if you do not obey the Lord your God … The Lord will strike you with … scorching heat and drought, with blight and mildew, which will plague you until you perish. The sky over your head will be bronze, the ground beneath you iron. The Lord will turn the rain of your country into dust and powder; it will come down from the skies until you are destroyed.” (Deut. 28:1–24)

Those festivals, of course, were specific to the seasons and the crops of Canaan. The New Testament church, which spans the globe from arctic to tropical climates, is not supposed to continue these practices of the old Law. However, Christians are still exhorted to learn from the Law’s wisdom (1 Cor. 10:11; 2 Tim. 3:16). The land- and climate-management laws of the Old Testament can help Christians appreciate the importance of climate stewardship today and the climatic damage caused by failing to steward God’s earth and its produce righteously.

Biblical climate changes

When a land does experience climate damage, God taught Israel to respond by asking why. When the land is “a burning waste of salt and sulfur. All the nations will ask: ‘Why has the Lord done this to this land? Why this fierce, burning anger?’” (Deut. 29:23–24).

Not every climate crisis is a work of judgment. The sufferings of Job included freak weather events (Job 1:16, 19), though he was innocent before God. Yet even Job responded with self-examination. Self-examination is an entirely Christian response to climate change and, when needed, can lead to moral and economic reforms. We see this pattern modeled by the Old Testament prophets.

The most dramatic example is the Flood in Genesis 6–9. God sent the Deluge as a direct response to human sin. Noah took practical steps, like building an ark. He also warned others, calling for repentance (2 Pet. 2:5). After the Flood, Noah received God’s promise:

“As long as the earth endures,

seedtime and harvest,

cold and heat,

summer and winter,

day and night

will never cease.” (Gen. 8:22)

Some Christians have taken that promise to mean God will never allow climate change after Noah. But God chose Moses, who came along many centuries later, to deliver the extensive aforementioned warnings about climate instability. So while God’s promise to Noah sets a limit on climate judgments, it does not justify climate neglect.

Biblical happenings long after Moses only confirm that. In the days of King Ahab, God sent another multiyear drought. But once Elijah led the people in repentance, “the sky grew black with clouds, the wind rose, [and] a heavy rain started falling” (1 Kings 17–18).

The prophet Isaiah tied climate instability to greed and abuse of the poor in his day (Isa. 32:1–20). The prophet Samuel cited unseasonal rains as a warning (1 Sam. 12:17–18). The Psalms point to the good order of the seasons as dependent upon the good order of the community (Pss. 65, 104). And the judgments attending Christ’s promised return also include climatic disasters (Mark 13:8; Rev. 6:8; 8:7; 11:19; 16:17-21).

The moral runs through both Old and New Testaments: A good climate is a gift, yes. But a worsening climate is a prompt to ask where we might be going wrong.

The witness of science

Because, according to Scripture, climate change is an expected instrument of divine humbling, we should be open to the evidence that it is happening now.

According to NASA, global temperatures have risen 2.1 degrees Fahrenheit since 1880. That may not sound like much, but it is enough to melt 428 billion tons of polar ice every year. This contributes to global sea levels rising 3.4 millimeters annually. Changes like these cause more severe storms, droughts, floods, and other natural disasters—events we increasingly see in news headlines and in our own communities.

The Bible does not tell us specifically about today’s climate change or what is causing it. But we do not need that kind of precision from the Bible. Scripture is sufficient in its reports about God’s works with his people of old, preserving those lessons to inform our response to comparable situations today. That includes the Bible’s teachings on the climate.

Once we recognize that climate change is often a means of divine reproof, the tools of science offer two kinds of help in our response.

First, science helps us identify areas of human activity. God, in his providence, is compelling us to give special examination to. Industrial-scale carbon emissions have been identified as the most significant factor contributing to global warming. This finding puts a providential spotlight on modern industrial practices. While secular policymakers focus on ways to reduce greenhouse gas emissions, the church should address matters of pride, greed, creation abuse, and other sins that may be connected to some industrial practices. Science, in conjunction with the convicting power of the Holy Spirit, can help us recognize areas on which to focus spiritual renewal.

Second, scientific evidence for climate change helps awaken unbelievers to the need to amend our ways. Many of those who would resist the call for reforms based on divine accountability will be more inclined to support such reforms when the need is scientifically demonstrable. Christians should not need climate science to motivate our embrace of climate stewardship. But having scientific data strengthens the motivation of unbelievers to pursue better climate stewardship.

Faith and science are not enemies. And climate policy is an area where Christian witness and scientific insight can collaborate productively.

A reforming influence

Today’s conditions are more stark than past climatic shifts, according to data collected by US government agencies. But climate changes have happened before. For instance, in the late Middle Ages, temperatures began to cool. During this period, known as the Little Ice Age, winters grew colder and longer. Responses were varied, but many across Europe turned to Scripture.

In his book Nature’s Mutiny, historian Philipp Blom writes, “Theological interpretations of climatic events were popular and frequently widely disseminated in print. Indeed, weather sermons became a minor literary genre of their own.”

For example, the Reformer John Calvin addressed crop failures amid weather changes in his day in his commentary on Genesis 3:18–19: “By the increasing wickedness of men, the remaining blessing of God is gradually diminished and impaired; and certainly there is danger, unless the world repent, that a great part of men should shortly perish through hunger, and other dreadful miseries. … The inclemency of the air, frost, thunders, unseasonable rains, drought, hail, and whatever is disorderly in the world, are the fruits of sin.” Calvin was not one to mince words.

Weather hymns were another feature of the age, Blom writes. For example, Paul Gerhardt’s 17th-century hymn, “Occasioned by Great and Unseasonable Rain,” says,

The elements o’er all the land

Are stretching out ’gainst us the hand,

And troubles from the sea arise,

And troubles come down from the skies.

One result of the Little Ice Age was a turning to the Lord. In fact, climate change is an often-overlooked component of the Reformation. This example encourages us, today, to likewise acknowledge when climate change is happening and respond with spiritual renewal.

Not all responses to the Little Ice Age were good. Without wisdom, interpreting climatic events as divine reproof can lead to something ugly. The period saw a sharp rise in witch trials. Something like 110,000 witch trials took place across Europe, half of which led to executions.

Such tragedies are a caution against misappropriating the theological implications of climate change. Better is the more sober, biblically centered example of the Reformation.

The present opportunity

One way or another, the changing climate will bring changes to human societies. Whether or not God is reproving specific sins, the increasing storms, droughts, and other consequences will afflict vast segments of humanity. And, as is often the case, the vulnerable will suffer most for the failures of the powerful.

The church is here to promote the work of redemption in such times. Christians risk squandering this opportunity for witness by denying or downplaying climate change.

The United Nations recently declared a “UN Decade on Ecosystem Restoration,” beginning this year. From 2021 to 2030, public and private cooperatives will endeavor to recover 350 million hectares of degraded land and remove up to 26 gigatons of greenhouse gases from the atmosphere.

There’s no reason the church can’t have equally bold visions for renewal in response to climate change. But our labors should aim for social and spiritual reformation alongside ecological renewal. Science can highlight the mechanics of climate change, and politicians can regulate behavior. It is up to the church to touch the conscience and bring a redemptive call to the culture. For in Christ:

The desert and the parched land will be glad;

the wilderness will rejoice and blossom.

Like the crocus, it will burst into bloom;

… they will see the glory of the Lord,

the splendor of our God. (Isa. 35:1–2)

Michael LeFebvre is a Presbyterian minister, an Old Testament scholar, and a fellow with the Center for Pastoral Theologians. He is the author of The Liturgy of Creation: Understanding Calendars in Old Testament Context.