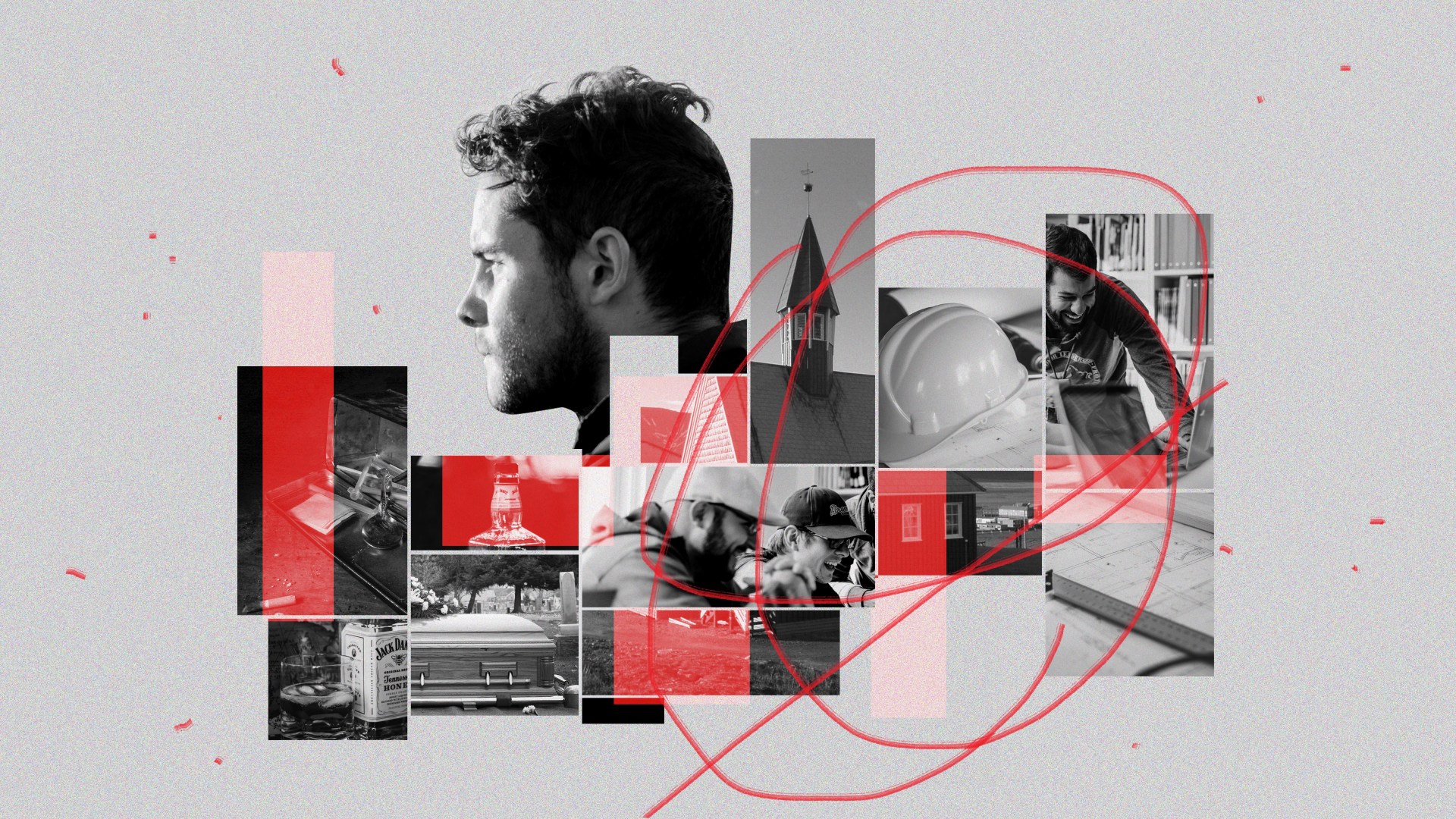

The average lifespan of American men declined in 2017. It declined in 2016 and in 2015, too. This loss isn’t equally distributed across the male population. Life expectancy in the US has long reflected inequality—the wealthy outlive the poor, and black Americans die younger than whites—but it has generally risen across demographics for a century. This recent decline, by contrast, is strongly tied to a specific group: less-educated white people, particularly working-class white men. And many of the deaths they’re dying early are of a specific type: suicide, drug overdoses, and diseases linked to alcohol abuse. Estimated to number around 600,000 in the past two decades, they’re called “deaths of despair.”

Our response to the new coronavirus will almost certainly multiply such deaths. Stay-at-home orders and social distancing more broadly exacerbate the conditions that foster deaths of despair.

This isn’t an argument for letting COVID-19 run wild—that would be deeply harmful too, as a grimly mounting death toll even with mitigation shows. Yet it’s much easier for someone like me to accept a stay-at-home order as the needful, ethical choice to save lives than it is for someone vulnerable to a death of despair . It’s easy for me, with a job I already did from home and a tech-savvy church and circle of friends, to opine about the necessity of fighting this pandemic. But if you live in a dying coal town in western Pennsylvania where what little work was available has been prohibited for weeks, and your internet connection is too slow to stream Mass, and you haven’t talked to your elderly mother in days because she can’t pay her phone bill, and your kid’s getting into drugs while the high school is closed—well, the value of drastic public health measures isn’t so clear.

There’s no single reason for deaths of despair , but three significant causes reflect both what we observe in communities where these deaths are rising and what Scripture tells us about human nature. All three causes will be intensified by this pandemic.

No Job

The first is economic hopelessness from lack of work. Unlike poverty or income inequality, a “consistently strong economic correlate [to deaths of despair] is the percentage of a local population that is employed,” reports the New Yorker. Research published there from Angus Deaton and Anne Case, a pair of Nobel Prize–winning economists, found “that the places with a smaller fraction of the working-age population in jobs are places with higher rates of deaths of despair, and that this holds true even when you look at rates of suicide, drug overdoses, and alcohol-related liver disease separately. They all go up where joblessness does.”

Of course they do! Loss of work has ramifications far beyond lower income. It affects our conception of ourselves, our worth, and our relationships. God’s design for humanity always has—and always will—include a balance of good work and good rest. God himself modeled this in the creation story of Genesis 1, and immediately thereafter tasked Adam with tending the Garden of Eden (Gen. 2:15). Jesus promised his followers abundant rest and an “easy” yoke (Matt. 11:28–29), not no yoke. And even the transporting vision of the new Earth in Isaiah 65:17–25 describes a humanity that still finds purpose in meaningful labor: “My chosen ones will long enjoy the work of their hands,” God says. “They will not labor in vain … for they will be a people blessed by the Lord.” When there is no good work to do, it is no surprise to find people in despair.

No Friends

The second cause is breakdown of local community. Our country (and indeed much of the Western world) has a crisis of loneliness. We don’t spend time with each other as we are made to do. We have dangerously declining levels of social trust and disintegrating institutions of civil society, as Robert D. Putnam detailed in his seminal book on the subject, Bowling Alone. “Without at first noticing,” Putnam writes, “we have been pulled apart from each other”—only now, the isolation of pandemic forces this reality before us every day, most vividly for those without the emotional insulation afforded by financial stability.

No Faith

Community dissolution is closely related to the third cause of deaths of despair: a decline in religiosity, by which I mean the institutions and shared life rhythms of an active and sustaining faith. “The woes of the white working class are best understood not by looking at the idled factories but by looking at the empty churches,” Timothy Carney argued in his 2019 book, Alienated America. Economics obviously matters, but Carney presents compelling statistical evidence that loss of church life is the most overlooked, important driver of despair.

This too is precisely what Christians should expect. When God declares in Genesis 2:18 that it is “not good for man to be alone,” he speaks of much more than the companionship of marriage. Scripture consistently calls us to a life together—not that there is never occasion for isolation, but that normal human life should be spent in community ordered around following Jesus. Part of the horror of the Crucifixion is Christ’s isolation (John 16:32), and the Epistles bristle with exhortations to be together (Heb. 10:24–25), eat together (1 Cor. 11:33), worship together (1 Cor. 14:26–27), and together “grow up in every way into him who is the head, into Christ” (Eph. 4:15–16, ESV). When church community dissolves, despair will crystallize.

All three causes of deaths of despair feed each other—“white Americans are less likely to attend religious services when they are unemployed,” Carney notes, and a church with less attendance is more likely to close, removing one more source of healthy community. All three causes are fed by this pandemic, too, and deaths of despairwill rise accordingly. For Christians, the challenge will be to work within the constraints of pandemic response to offer whatever relief, hope, and solace we can; to speak out for the despairing (Prov. 31:8–9); and to fight the evil of loneliness for every inch it tries to claim.

Bonnie Kristian is a columnist at Christianity Today, a contributing editor at The Week, a fellow at Defense Priorities, and the author of A Flexible Faith: Rethinking What It Means to Follow Jesus Today (Hachette).