The novel coronavirus now dubbed COVID-19 has struck fear around Asia and the world. As many as 760 million people in China have been quarantined, and perhaps 110 million are barred from even exiting their apartment, all as part of China’s effort to prevent a pandemic.

In Hong Kong, where my wife and I serve as missionaries in the Lutheran Church-Hong Kong Synod, school has been cancelled since late January. Kids began doing online classes last week, and they will not return to school until mid-March at the earliest. Restrictions on public activities and gatherings have spread throughout much of Asia, as individuals seek to reduce their risk of infection. Unsurprisingly, church attendance, especially among families with children, has plummeted.

However, the quarantines and cancellations associated with COVID-19 offer a remarkable opportunity. Families are stuck indoors for weeks on end. Employers are telling employees to work from home and giving more flexible arrangements. Kids finish their homework in just a few hours, leaving the day open for activities. Although it’s a terrible situation, nonetheless it opens a door for Christian families to step into a regular practice of home discipleship.

Although Christians in China are facing a special tribulation today, the same principles apply to those living in the States and elsewhere. In times of both severe crisis (think Hurricane Katrina victims stuck in the Superdome) and also mundane inconvenience (think of the odd snow day or sick day), we can seize the opportunity for the most important education of all, more essential than literacy, more useful than math, more formative than history: catechesis!

What the Numbers Tell Us

Research on the effectiveness of childhood catechesis is frustratingly sparse. There is some evidence suggesting that religious schools boost adult religiosity, particularly among Jews and Catholics. Specific changes in curriculum at religious schools seem to alter student religiosity. Internationally, Islamic schooling seems to substantially alter the value judgments children make. When France restricted religious education in the late 19th century, it did reduce religiosity. Christian high schools in America do seem to impact students’ self-reported values. And a large longitudinal study (using data from the National Longitudinal Study of Adolescent and Adult Health) found that religious schooling increased religiosity as a young adult.

This data, although significant, doesn’t address the faith instruction that happens in the home. Two longitudinal studies exist that have enough data to assess how family religious practices impact adult religiosity, and a third contemporary study provides supporting evidence.

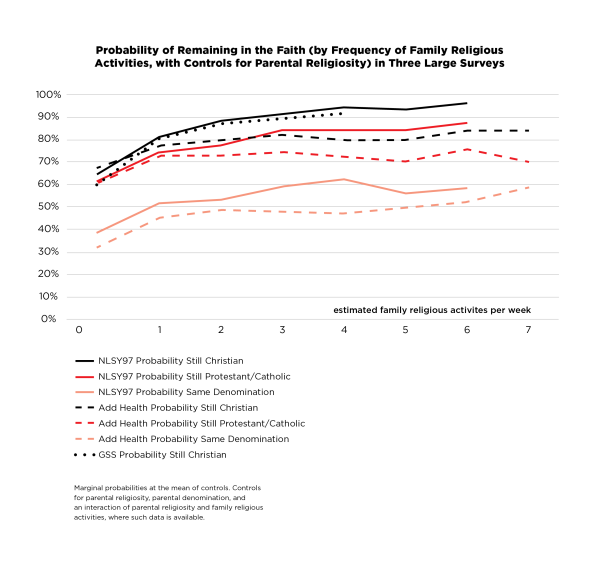

The National Longitudinal Survey of Youth 1997 Cohort (NLSY97) surveyed American kids who were teenagers in 1997 (and also the parents of those teens), then followed up with them in later years. This study, while not primarily about religion, includes data on how many days per week families did religious activities together, as well as data on the child’s religiosity when they reached age 30. The total sample size included over 3,500 individuals.

The National Longitudinal Study of Adolescent and Adult Health (called “Add Health”) also tracks a cohort of 3,800 teenagers in the mid-1990s to around age 30. This survey does not include an explicit measure of family religious activities, but it does ask about which family members attend church together, whether kids attend youth religious activities, and whether family members attend special church events.

Finally, the General Social Survey (GSS) contributes to the picture. Although it’s only a cross-sectional survey, in several years it included retrospective questions about religion, asking respondents how often they attended church as kids and whether their mother and father attended church. This information enables an estimate of household-wide church attendance that can be compared to adult religiosity in later years.

These surveys together provide enough data to explore a very interesting question: If we control for the intensity of a parent’s religious beliefs and also control for their specific denomination, how much does a greater level of family religious activity influence the odds that a teenager stays in the faith at age 30?

In preparing for this report, I tracked three different measures of religious retention.* One simply asks if the teenagers in question are still Christian at age 30. (“Christian” is defined as self-identifying with any denominational family that has historically confessed a belief in the Trinity.) Another measure gets more specific and asks if those teenagers are still located in the broad tradition they were raised in: Catholic, Protestant, or Orthodox.

Finally, another tracks 18 denominational families. Sample sizes are too small to track specific denominations, so rather than track odds that a child remains Southern Baptist, I track the odds that they remain Baptist of any kind. (This caveat is significant, since most denominational groups have major theological variation.)

In all cases, a higher frequency of family religious activity for a child is associated with greater odds of remaining Christian, remaining within a broad religious tradition, or remaining within a given denomination family. The size of the effect varies and is not enormous, but nonetheless the major results are still statistically significant. More than being statistically meaningful, however, they are spiritually meaningful: They show that what happens in the family really does matter.

Worship Where You Live

So how does this all cash out? Families who pray and worship together tend to continue praying and worshipping together. The key to successful transmission of Christian faith across generations is not more youth groups or hipper pastors but the Holy Spirit working through the vocation of parenthood as parents take the time to share their faith with their own children.

That said, Christian parents do not catechize their children because social science says that catechesis works. We catechize our children because we are commanded to do so by God in Proverbs 22; Ephesians 6; Deuteronomy 4, 6, and 11; 1 Timothy 4; and by the very words of Christ in Matthew 19. When we fail to catechize our children, we sin against them, and the warning of Christ in Matthew 18—that “it would be better for [us] to have a large millstone hung around [our] neck and to be drowned in the depths of the sea” (v. 6)—must weigh heavily upon us.

But nonetheless, we can be encouraged by worldly evidence that backs up this calling and tells us that, yes, what we do at home has an enormous impact on our kids’ future faith. Controlling for parental religious beliefs, the odds that a child will leave the Christian faith are between one third and seven times greater in a household with little or no in-home catechesis than in a household where the family has regular religious practice together.

During the current coronavirus scare and other parallel situations, both small and large, this data can be comforting for Christians. We can anchor our children against the chaos of the outside world on the steady rock of faith. These times of upheaval reduce our ability to guarantee our kids a prosperous, educated, and stable life, but they simultaneously make it easier for us to find time to talk to them about the eternal life Christ has given us.

If we seize the opportunity handed us to initiate a practice of faithful family togetherness, then whether we get our kids enough masks and hand sanitizer, we can still be confident of the endurance of their faith unto life everlasting.

Lyman Stone is an adjunct fellow at the American Enterprise Institute, a research fellow at the Institute for Family Studies, and the chief intelligence officer of the consulting company Demographic Intelligence.

* Each survey uses different measures of parental religiosity and religious activities. NLSY97 has the most extensive detail on parental religiosity and also explicitly asks about family religious practice, thus its estimate is most reliable. Add Health estimates of parental religiosity are of good quality, but teenage religious practices include both family-centered activities and also youth group activities. Because families that send their kids to youth group or youth retreats, or that attend religious services together, are probably more likely to also pray together at home, I include these non-family activities. But the Add Health measure of teenage religious activities is better seen as a loose index of those activities, not a literal count like NLSY. GSS has the worst-quality data, with no direct measure of parental religious feeling or belief and only family-wide church attendance as a childhood religiosity variable, thus it should be seen as only a very suggestive measure.