We used to dance to kings but now we are dancing to God,” explains Omot Ochan, the worship leader for the Anuak service at Christ Lutheran Church, near St. Paul, Minnesota.

The music at his church begins as a high-pitched offering, a young woman’s ethereal voice floating through the sanctuary, before meeting a fervent response from congregants and the rhythms of three drums. Most of the parishioners at the service were refugees from the Gambela region in western Ethiopia, which borders South Sudan. Now, they live out their faith in the Midwestern suburbs, surprised to find empty church buildings in a country they once assumed was overwhelmingly Christian.

In the United States, the two largest US Lutheran bodies—the Lutheran Church Missouri Synod (LCMS) and the Evangelical Lutheran Church in America (ELCA) are around 95 percent white, and the denomination is slowly in decline in the Global North. But Lutheran membership in the Global South is growing. As of 2016, the largest Lutheran bodies are found in Tanzania and Ethiopia; they now rank ahead of Sweden, Denmark, Finland, Norway, and the US.

The revivalist spirit of these Lutheran newcomers is often expressed in a most Lutheran way—music. As Martin Luther himself once said, “Music is next to theology.”

In another Minneapolis suburb, Sudanese Lutherans sing Luther’s “A Mighty Fortress” in the Nuer language, accompanied by a resonant drum. This rendition of the denomination’s most famous hymn is hardly reconcilable with its German predecessor, proof that even the most eminent songs can be reproduced in profoundly different ways.

One God, Many Traditions

I set out more than ten years ago to answer a few questions: What can immigrants and refugees teach us about Christianity in the United States and globally? More locally, what does it feel like to be Lutheran and an immigrant in Minnesota? What does the music at immigrant congregations reveal about the history of religious journeys?

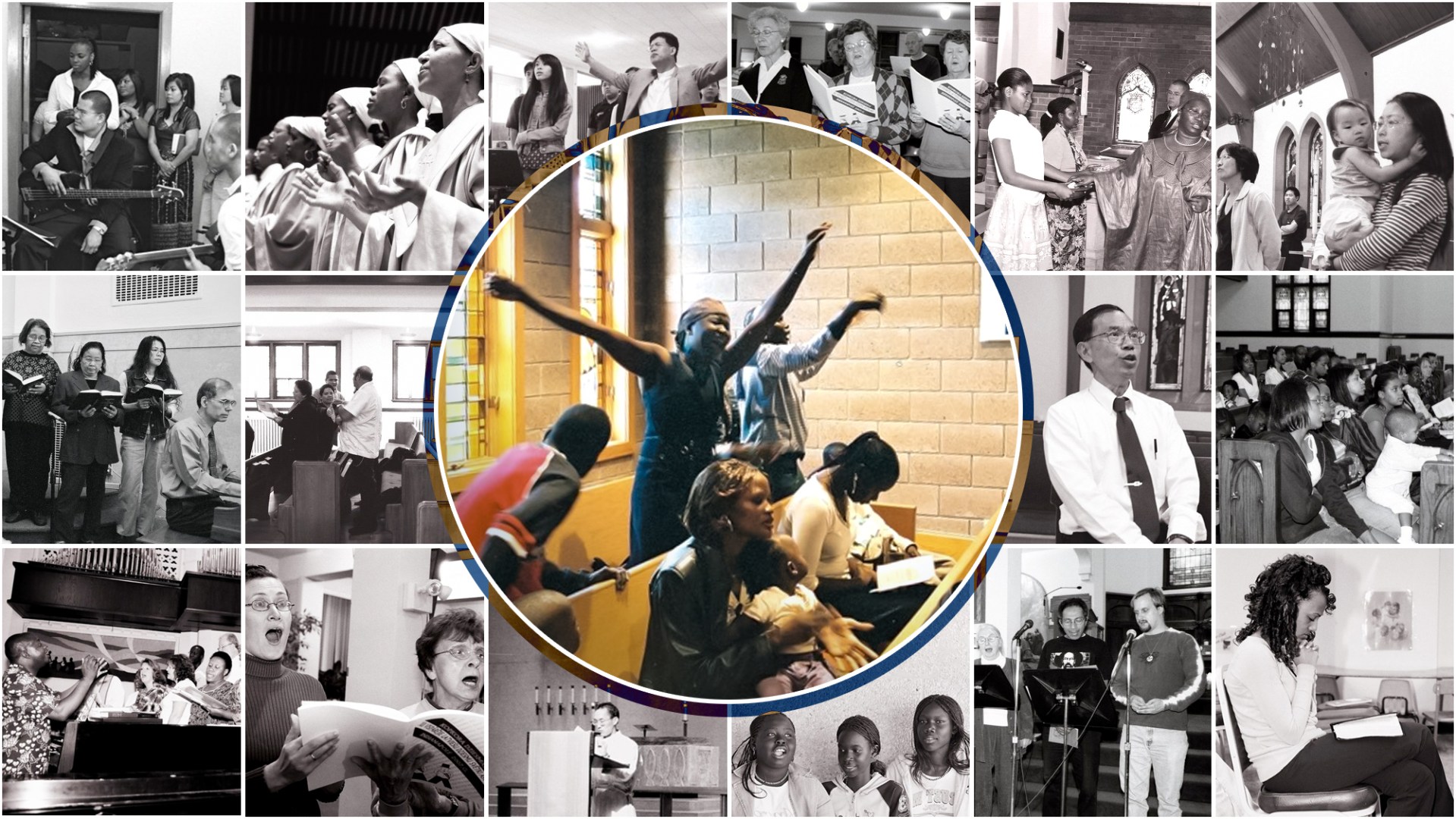

I visited churches with congregations from Tanzania, Laos, Liberia, Cambodia, China, Sudan, and Ethiopia, all within a roughly 30-mile radius of Minneapolis and St. Paul. By attending almost 20 churches that did not worship in English, I learned that the music differs dramatically from church to church. It’s impossible to even try to connect it, even though the congregations exist just a few miles from one another and all self-identify as Lutheran.

Some worshipers hail from countries with Christian histories that stretch back centuries. They grew up singing in Lutheran choirs in their homeland, as their ancestors did. Those from countries with a longstanding history of European colonization or mission work, like Tanzania, carry with them the most obvious signs of European musical influence.

The Swahili congregation at Minneapolis’s Holy Trinity Lutheran Church might sing in precise four-part harmonies, for example. But its music is also distinctively Tanzanian: The lyrics are in Swahili, sung in a call-and-response form common across many sub-Saharan African music, and accompanied by a drum and shakers.

Some congregations I visited had never sung in a group before arriving in the US, like the Lutherans of the Khmer Choir at Christ Lutheran on Capitol Hill in St. Paul. There was little in the way of group singing as a cultural practice in Cambodia, though music itself has always been highly valued.

Bun Leoung, a celebrated Cambodian musician who co-directed the choir, was spared by the Khmer Rouge, which outlawed religion in the 1970s, because of his talent on the tro khmer (fiddle). He converted to Lutheranism in the US and played the tro with the Khmer choir until he passed away. The choir’s favorite hymns are an unusual combination of folk tunes and harvest songs, accompanied by both the piano and the tro.

Khmer-English translator Thaly Cavanaugh describes the power of singing in the Khmer choir, regardless of whether non-Cambodian congregants understand the lyrics:

When you sing [the word of God], you sing from your heart and soul. And, you feel the joy and are able to share it. We get comments about how [the rest of the congregation] appreciates our Cambodian choir. They don’t even know what we are singing, but they can read the translation [in the bulletin]. It’s a big part of their lives and that helps motivate and inspire us, knowing that we work together for a common faith.

Some groups, like the Anuak congregation at Christ Lutheran Church, have largely converted to Christianity in the context of a refugee camp. East African Anuaks are relatively new to Lutheranism, and it shows in their music. Songs are always started by a female “call” that is responded to by the group. Accompaniment involves hand claps and shakers, most of the time using three two-sided drums and sometimes featuring a synthesizer. The call-and-response structure is not unfamiliar to US Christianity, but the tone quality of the singers and ululations distinctively place the music back in the heartland of the Gambela region of Ethiopia.

A New and Joyful Noise

All of these congregations make music to both remember their roots and plant new ones.

While Orthodox Christianity has been practiced in Ethiopia since the fourth century, Protestantism gained popularity more recently. The musical style at Our Redeemer Oromo Evangelical Church, an ELCA congregation in Minneapolis, is derived from the Lutheran Ethiopian Evangelical Church Mekane Yesus (EECMY), founded in 1959. The church is made up of Protestants from Oromia, Ethiopia, and is considered the mother church for Oromo Diaspora churches. It is also one of the largest immigrant churches in the ELCA.

The musical introduction to the service can take up to 45 minutes. During a heavily amplified prelude led by vocalists and a keyboard, choir members dance in the aisles and church members may speak in tongues. The slow-fast-slow tempo of the music sets the mood of the congregants, who appear reflective, then ecstatic. Flexibility and improvisation, two characteristics virtually absent from most Euro-American services, are key elements to the spontaneity that make the service so exhilarating.

Not every congregation is a new, ethnically homogenous group. In some places, integration has gone a step further. Such is the case at Christ Lutheran on Capitol Hill in St. Paul, one of the most diverse Lutheran churches I visited. Here, Cambodians, Africans, white Americans, and African Americans all worship together. The music is accordingly diverse: The traditional choir sings songs in English and the Khmer choir sings Cambodian folk tunes set to Christian lyrics. Congregational singing is entirely new to the Cambodian Americans who have chosen to join the choir.

Paul Swenson, the white, US-born accompanist of the Khmer Choir at Christ Lutheran on Capitol Hill, observes how the deep faith of his fellow Cambodian Lutherans manifests in their music. While European-descended Lutherans have inherited their tradition and may simply sing the hymns because “we’ve always done it that way,” he said, these newcomers are adopting and adapting hymns in ways that require searching and examination.

Because of that work, Swenson said, “In a sense, I think their faith is more vital, more alive.”

Allison Adrian specializes in ethnomusicology and musicology at St. Catherine University in St. Paul, Minnesota. She recently served as a Fulbright Scholar in Ecuador where she studied how migration and globalization have influenced indigenous music-making in the Andes.