Recent legal attempts to balance religious freedom with LGBT anti-discrimination efforts have been compared to the push for racial equality during the civil rights movement in the United States decades before. But when conservative Christian-owned businesses decline to serve same-sex weddings, are the same principles at stake as when white-owned businesses refused to serve African Americans?

Justice Clarence Thomas, the only African American on the Supreme Court, brought up the comparison in his concurrent opinion in this month’s Masterpiece Cakeshop ruling. “It is also hard to see how [baker Jack] Phillips’ statement is worse than the racist, demeaning, and even threatening speech toward blacks that this Court has tolerated in previous decisions,” he wrote, citing past rulings in favor of cross burners and organizers of racist parades.

Though Thomas joined the 7–2 majority siding with Phillips’s First Amendment rights in the case, the American public is largely split over whether wedding vendors should be required to serve same-sex couples or if they should be free to turn down clients if they have religious objections, the Pew Research Center found in a 2016 survey.

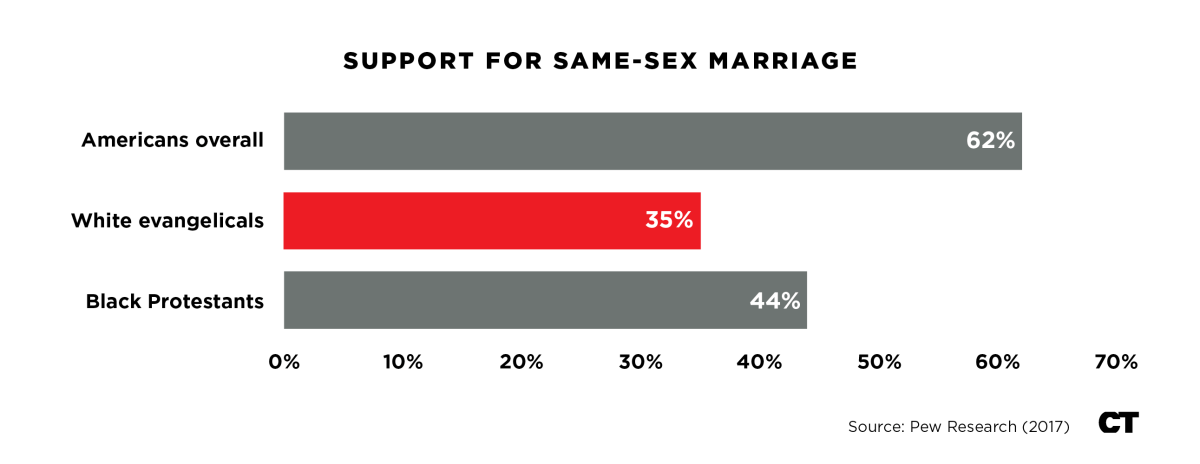

While American evangelicals have been the biggest supporters of Phillips’s case and the many similar cases, that support breaks down on racial grounds. Though both black and white born-again believers have long been the US religious groups most likely to oppose same-sex marriage, more African Americans don’t want to see owners refuse service to a particular group.

Pew found that black Protestants (most of whom identify as evangelical) were twice as likely as white evangelical Protestants—46 percent vs. 22 percent—to say businesses should be required to accommodate gay weddings. Among weekly worshipers, the difference was even more stark: 43 percent of black Protestants said businesses must provide services to same-sex couples; only 10 percent of white evangelical Protestants said the same. Meanwhile, 59 percent of white evangelicals sympathized only with the view that service refusals can occur for religious reasons, while only 27 percent of black Protestants said the same.

Christianity Today asked African American Christian leaders to weigh in on the Masterpiece Cakeshop decision and how the church can prioritize religious freedom while considering the broader concerns over discrimination.

Charles Watson Jr., associate director of education at the Baptist Joint Committee for Religious Liberty:

Theology plays a major role in the different reactions of African Americans to court cases surrounding same-sex marriage, but America’s racial history is equally as important. Many black Protestants and black evangelicals remember “God” being invoked to justify horrendous acts of violence and discrimination. These acts were supported by religious fervor, conviction, and sincerity from the church as well as our judicial system. A prime example would be the 1967 Loving v. Virginia case that cited a judge who proclaimed, “Almighty God created the races … The fact that he separated the races shows that he did not intend for the races to mix.”

Even with similar theology about same-sex marriage, people will wrestle with how that plays out in commercial settings and in the lives of their loved ones.

For those who believe every customer should be served no matter what, I remind them that the religious convictions of the business owner have to be taken seriously and sincerely. I ask them to think of a core belief that they themselves wouldn’t want to violate. For those who believe business owners should be able to refuse certain customers based on belief, I ask them think of what it would be like not to be served based on their identity or someone else’s religious convictions.

My former barber and I often discussed these issues. I would ask, “If I were getting married to a man tomorrow and asked you to cut my hair for the ceremony, would you?” His response was, “Yes, what you do after I render my service is your business.” Since he also sings at weddings, I asked, “Would you sing at that wedding?” He responded, “That’s a little much for me.”

People of faith on different sides of the issue must be willing to have these conversations and acknowledge that the answer often depends on context.

Lisa Robinson, theology blogger and editor of Kaleoscope:

As an African American woman, it might seem reasonable for me to have qualms about the recent ruling the Supreme Court delivered in support of a Christian baker. Jack Phillips’s refusal to serve these individuals smacks of the same kind of infringement that African Americans in this country experienced. However, three factors give me pause in this line of thinking and lead me to applaud the Supreme Court’s decision.

First, the case is not about discrimination, but religious conscience. The civil rights movement was started because a whole class of people were pervasively denied acceptance based on who they were biologically. Discrimination ensued because they weren’t deemed to be fit to share the same services, space, or civic obligations in a white society.

The Masterpiece Cakeshop case wasn’t about the people, but the ceremony. I think likening the two cases—discrimination against blacks and denial of cake-baking for a ceremony—undermines the cause of the civil rights movement, which was about affirming the dignity of personhood irrespective of lifestyle choices.

I can appreciate arguments that say whites believed upholding the purity of races was rooted in their Christian convictions; however, the racist line of thinking that prevailed for so long has no basis in Scripture (consider the marriages of Solomon and Moses), whereas endorsing same-sex marriage is explicitly prohibited.

Second, reliance on state-sanctioned intervention can have negative implications for how we value fellow image bearers apart from their choices. I confess that I have a love-hate perspective toward the governmental intervention needed to address discrimination against African Americans. Unfortunately, we ultimately had to rely the state to define discrimination rather than God himself and his requirements for what kind of activity his people should or should not support.

Lastly, equating refusal to participate in same-sex ceremonies with active discrimination against a class of people puts us in a precarious position of lending support to same-sex marriage because we don’t want to reject people. We ought to be free to distinguish between the value of persons and the values they espouse. At the end of the day, commitment to Christian convictions matters most.

Kathryn Freeman, director of public policy for the Christian Life Commission of the Baptist General Convention of Texas:

Many African Americans are cautious in their response because there was a time in this country when religion was used as a reason to exclude them from many facets of American life. Because of this history, they tend to be more focused on procuring their freedom from racial injustice than religious freedom. But I think many African American Christians are also aware of anti-Christian animus in public life.

The majority culture could take some lessons from the black church tradition on what it means to live as a prophetic minority when the larger culture rejects your worldview, as many rejected Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. then and reject former San Francisco 49ers player Eric Reid now.

We cannot retreat from public life. Our faith is an important part of our lives and should be reflected in all we do, but we must also learn to live with and love those with whom we disagree.

Justin Giboney, attorney and founder of the AND Campaign:

The free exercise clause gives Americans of all faiths the right to maintain and live out unpopular or even offensive religious beliefs despite sincere opposition based on the spirit of the day. Without this protection, our timeless convictions would be subject to the ever-changing preferences and whims of the world around us.

Unfortunately, American Christianity has a history of using its faith as a pretext or even justification for bigotry and hate. African Americans have often been on the receiving end of this practice. We’ve had to reconcile how a faith that revealed the source of human dignity to the world could be misused to promote behavior and systems denying the same. Decades of racial violence and discrimination proved that the Christian label doesn’t guarantee Christ-like compassion.

It’s not surprising that black Protestants are more likely to believe vendors should serve same-sex weddings than their white counterparts. We might agree theologically, but historically speaking, we have little reason to believe the concerns aren’t pretext for prejudicial impulses. There’s very simply a lack of trust, and it’s better to err on the side of caution than to be complicit in furthering bad faith and un-Christlike endeavors.

Christians are required to be impartial and sacrificial in our commitment to living out the Bible’s “love thy neighbor” mandate. This obligation is unconditional, extending even to those with whom we fundamentally disagree. Thus, our first instinct should be to embrace and serve others, especially when our talents and resources have been requested.

That said, the biblical love and service imperative is coupled with truth-telling and a responsibility to honor what God has deemed good. Accordingly, we must also profess God’s Word and refrain from participating in certain activities that obscure his design even when our witness conflicts with the sensibilities of the larger society. Thus, a pastor—or a baker—who’s been asked to participate in a wedding ceremony should be able to refuse if compelled by religious conscience; however, services generally should not be declined outside of very limited circumstances.