Two recent documents remind us of the importance of doctrinal clarity and how hard it is to achieve unity on doctrine.

The Nashville Statement addresses a burning issue of our day: human sexuality. The social and political pressures to deny the biblical teaching on God’s intent for our sexuality are immense, and we believe the statement’s creators clearly grasp the need to stand firm. This is not merely an ethical debate about what one can and cannot do in the bedroom; in fact, on this issue rest crucial aspects of the doctrine of Scripture and theological anthropology.

Unfortunately, in attempting to clarify classic orthodox belief, the Nashville Statement ended up confusing some issues and has divided advocates of biblical sexuality. This is in part because it was largely driven by The Council on Biblical Manhood and Womanhood (although the group had conversations with other organizations) and lacked broader participation, failing to garner a consensus among those most deeply sympathetic to its main affirmations.

For example, the Nashville Statement says, “We deny that adopting a homosexual or transgender self-conception is consistent with God’s holy purposes in creation and redemption.” This critiques those who, while honoring the Bible’s teaching to refrain from same-sex relations, still describe themselves as “gay Christians.” Some signers of the statement have argued that our identity cannot be grounded in a broken state but instead must be grounded in Christ. This argument fails to appreciate the nuances of identity, however.

Take the parallel example of Christians who are alcoholics—an admittedly tired and imperfect comparison but one that is still apt. Some long for peace and relief from anxiety—this is a good longing!—but believe alcohol is a shortcut to that end. They discover, of course, that this can become their idol at best and their destruction at worst. The attraction to alcohol is so strong and destructive, the recovering alcoholic stands at an AA meeting and identifies himself by his brokenness: “My name is John, and I’m an alcoholic.”

Of course his ultimate identity is in Christ. But alcoholism gives alcoholics deep insights into themselves and others like them, not to mention into the mercy and goodness of God—so much so, they can say their alcoholism is a “gift.” They don’t mean this literally because that would make God the author of evil. Instead, they are speaking with Paul when he revels in his weakness, for his thorn in the flesh was, in fact, the means by which he had a deeper experience of God’s grace (1 Cor. 12).

God’s original intent is that all men and women have heterosexual desires. In fact, as Wesley Hills notes in Spiritual Friendship, even at the root of same-sex attraction lies a genuine good: the longing for deep friendship. But like all good longings, this can go awry, and like all things that can go awry, God is more than able to redeem it.

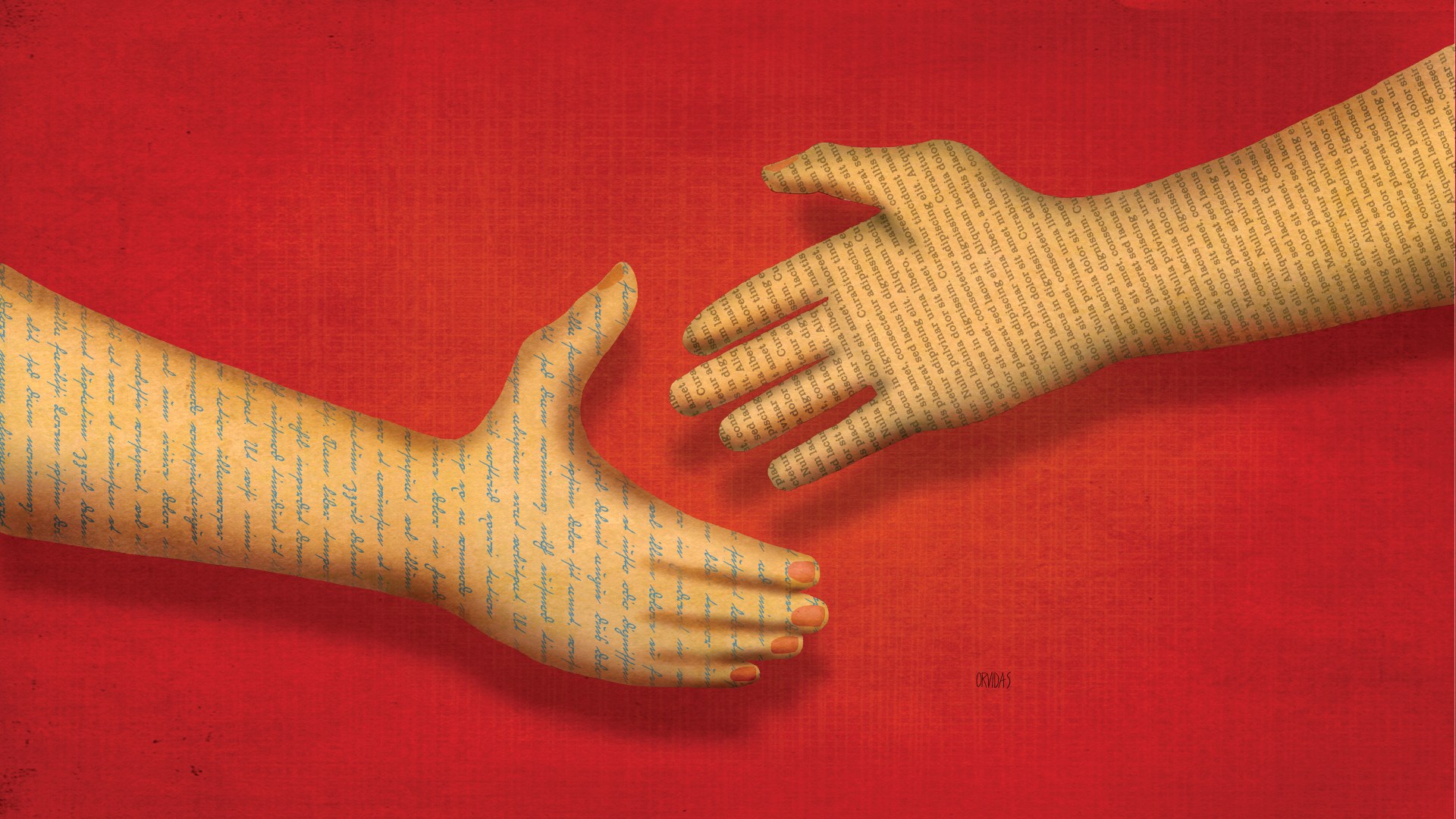

In contrast to the Nashville Statement, the Reforming Catholic Confession (RCC) includes wide representation in seeking a unified confession, and thus stands on steadier ground from the beginning. It addresses the argument that the Reformation is mostly a tragedy, having led to more church divisions than ever. But Protestants have believed that genuine unity can transcend church structures, and the RCC wisely outlines how orthodox Protestants across the world are in fact unified on a range of core and distinctive theological issues.

Both documents attempt to articulate core Christian beliefs, and both need time and discussion to clarify what they do and do not say. The RCC grasps that, recognizing the need to “continue the discussion, humbly listening to one another as we together harken to God’s word.” Unfortunately, some are already using the untested Nashville Statement to determine others’ orthodoxy or as a requirement to join their organization. This is premature. We recall The Chicago Statement on Inerrancy of 1978, which reads,

We invite response to this statement from any who see reason to amend its affirmations about Scripture by the light of Scripture itself, under whose infallible authority we stand as we speak. We claim no personal infallibility for the witness we bear, and for any help which enables us to strengthen this testimony to God’s Word we shall be grateful.

May we in the evangelical community approach these documents with the same humility and patience.

Mark Galli is editor in chief of Christianity Today.

Do you agree? Disagree? Let us know here.