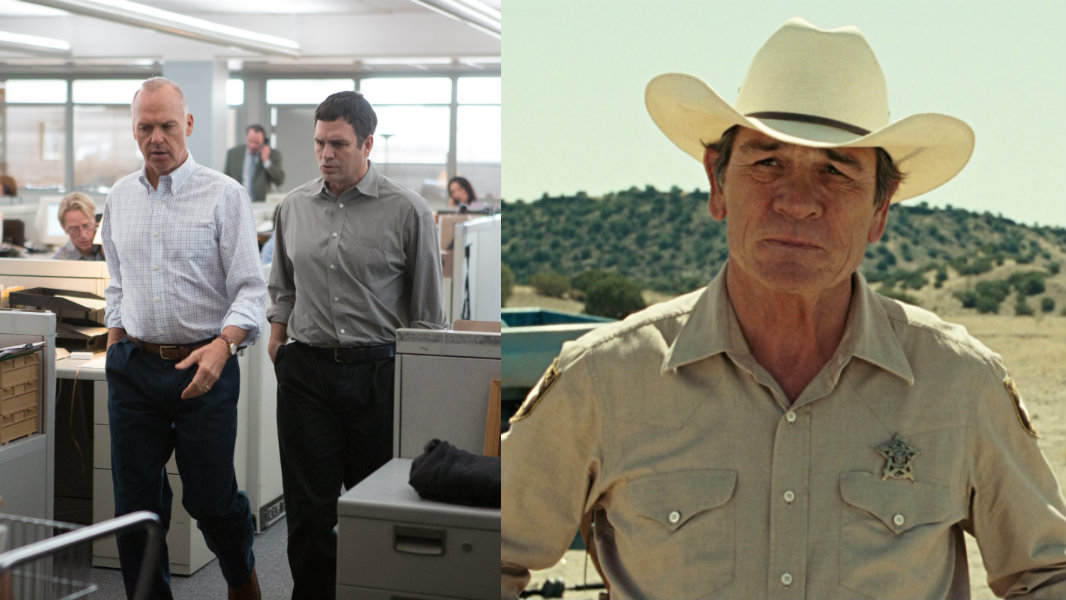

Open Road Films

Open Road FilmsAs I left the theater after seeing Spotlight, two members of the film’s publicity team asked for my thoughts on the film. I fumbled for words and said I was heartbroken. My wife mercifully pulled me away before I broke out in tears.

Spotlight left me helpless. The film, which tells the true tale of the Boston Globe investigative journalism team that uncovered the child molestation scandal in its local Catholic archdiocese in 2002, ends with a list of cities in which similar abuses have been discovered. I was overwhelmed by the scope of the atrocity, the knowledge that this sin-crime is not solely a Catholic problem, but a Christian problem, and the horror of realizing I, too, am complicit in this systemic injustice.

(Read CT’s review of Spotlight.)

Spotlight focuses on the little things that accumulate over time to create systems that either function well or deplorably. We watch characters have endless conversations with lawyers who won’t say anything; knock on doors hoping to get impromptu interviews, only to have them slammed instead; wait in government offices for hours only to be told they’ll have to come back tomorrow; and comb through decades of directories showing which priests were assigned where and when and for what reason.

These small investigative gains eventually yield great results, but the process requires Herculean patience. (The film subtly suggests that kind of patience is rarely seen—and even more rarely funded—in today’s “hot take” world.)

And Spotlight also shows how it was small decisions, all made in parallel, that created the kind of system that could allow child abuse to proliferate. People look the other way, or look at isolated instances instead of the big problem, or just choose to give up because the problem is too big. Some get distracted by everyday concerns. Some even retreat to catechisms instead of facing contemporary questions that require contemporary answers.

Spotlight damns a system that allows children to be abused by spiritual authorities and convicts everyone, including the reporters who failed to bring the story to light a decade before, allowing another generation of children to be abused.

Open Road Films

Open Road FilmsThis weighs heavily upon me. I’ve sat and tried to make sense of the evil the film records. (I’ve seen it three times now, and I’ve been working on this piece for two months.) I’ve tried to discern my place in the vastness of it. It is so big. I am so small. How could this happen? What can be done?

Where is God in all of this?

How can I stay committed to the institutional church if this abuse is the kind of thing the institution cultivates? Why did “God-fearing” Christians allow this to continue for so long? I know that this system of abuse broke God’s heart, but why didn’t it break the hearts of more Christians? Do I really want to count myself among them if this is the kind of thing they allow to continue?

These questions aren’t particular to me and my wrestling with Spotlight. The most recent Pew Research study on religious life in America reveals that between 2007 and 2014, American Christians unwilling to identify with any established tradition or denomination grew 6.7 percent while all other affiliations fell by as much as 3.4 percent.

So in addition to my spiritual community and the Bible, I turned to an unlikely place to help me make sense of it all: the movies. Even more unlikely, the film that helped me was Joel and Ethan Coen’s No Country for Old Men.

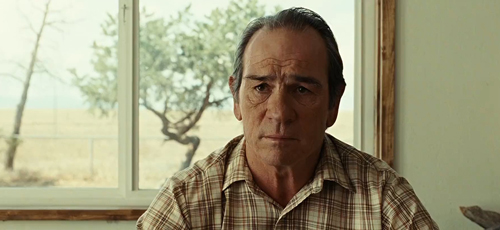

Miramax

MiramaxNo Country for Old Men is a movie about men motivated by greed doing terrible things to other people. In part, it explores whether people who long and work for justice can find hope in a brutally unjust world. It is concerned with the senselessness of evil and evil’s power in these times. (The film is set in the 1980s, which to me has always suggested that things may be even worse now.)

No Country for Old Men is about one man, Sheriff Ed Tom Bell (Tommy Lee Jones), searching for meaning among the bloodshed. He doesn’t find it, so he searches for hope instead. Any hope he finds is hard won.

In the film’s opening monologue, Bell says:

The crime you see now, it’s hard to even take its measure. It’s not that I’m afraid of it. I always knew you had to be willing to die to even do this job, but I don’t want to push my chips forward and go out and meet something I don’t understand. A man would have to put his soul at hazard. You’d have to say, “Okay. I’ll be part of this world.”

That’s exactly how I feel watching Spotlight, how I feel as I contemplate my work for a seminary training pastors, and how I feel as a Christian committed to maintaining a relationship with the institutional church. The more I learn about the abuses of power that are too common in institutional Christianity—abuses that extend beyond sexual abuse—I feel like I have to “put my soul at hazard” to remain “part of this world.”

Miramax

MiramaxIn Spotlight, reporter Mike Rezendes (Mark Ruffalo) asks one character how he can call himself a Catholic knowing what he knows about the prevalence of child abuse amongst priests. (Rezendes and Sacha Pfeiffer [Rachel McAdams] discuss this amongst themselves at another time in the film as well. It’s a quandary very much on the film’s mind.) The response is that it’s tricky, but he tries to think of the Church as something eternal and the institution as a temporary thing—“temporary,” that is, in relation to the eternal.

I think that’s what we all have to do. We have to admit the contemporary injustices left to fester by the institutional church. We have to own those. And we have to remain committed to rooting them out. To do that, we have to remain committed to the institution. Christ’s incarnation suggests that change happens from the inside. Spotlight suggests that while change can be inspired by outsiders (like new editor Marty Baron), it’s only when those within the system change that the system itself changes.

Miramax

MiramaxAnd we have to keep the eternal in view. Here, Sheriff Ed Tom Bell helps us again.

At the end of No Country for Old Men, after Sheriff Bell has investigated and pursued greedy, violent men and found only heartache, he retires from his work. I don’t see this as an act of hopelessness. Being willing to rest is often an act of faith that something beyond you is ultimately responsible for the completion of your work. In retirement, he recounts a dream in which, though the night is dark, he sees a fire up ahead waiting for him when he gets there. This suggestion of a hopeful image (it’s delivered via dialogue only) closes the Coens’ in large part hopeless film.

I am not yet at the end of my life. I have many years of justice-minded work ahead of me, much of it, no doubt, in service of the institutional church. I will recognize the temporary problems, work to fix them, but keep an eternal mindset through it all. I will keep my eyes fixed on that fire in the distance.

As Spotlight suggests, change will come because I do what I can with my talents and skills in concert with others to root out injustice in our system. There is work yet to be done. As No Country for Old Men suggests, the work will be carried on by those who come after me. It will be completed by One beyond me. And in that, there is hope.

Elijah Davidson is co-director of the Reel Spirituality initiative at Fuller Seminary's Brehm Center. He received his Master of Arts in Intercultural Studies and Theology and Art at Fuller.