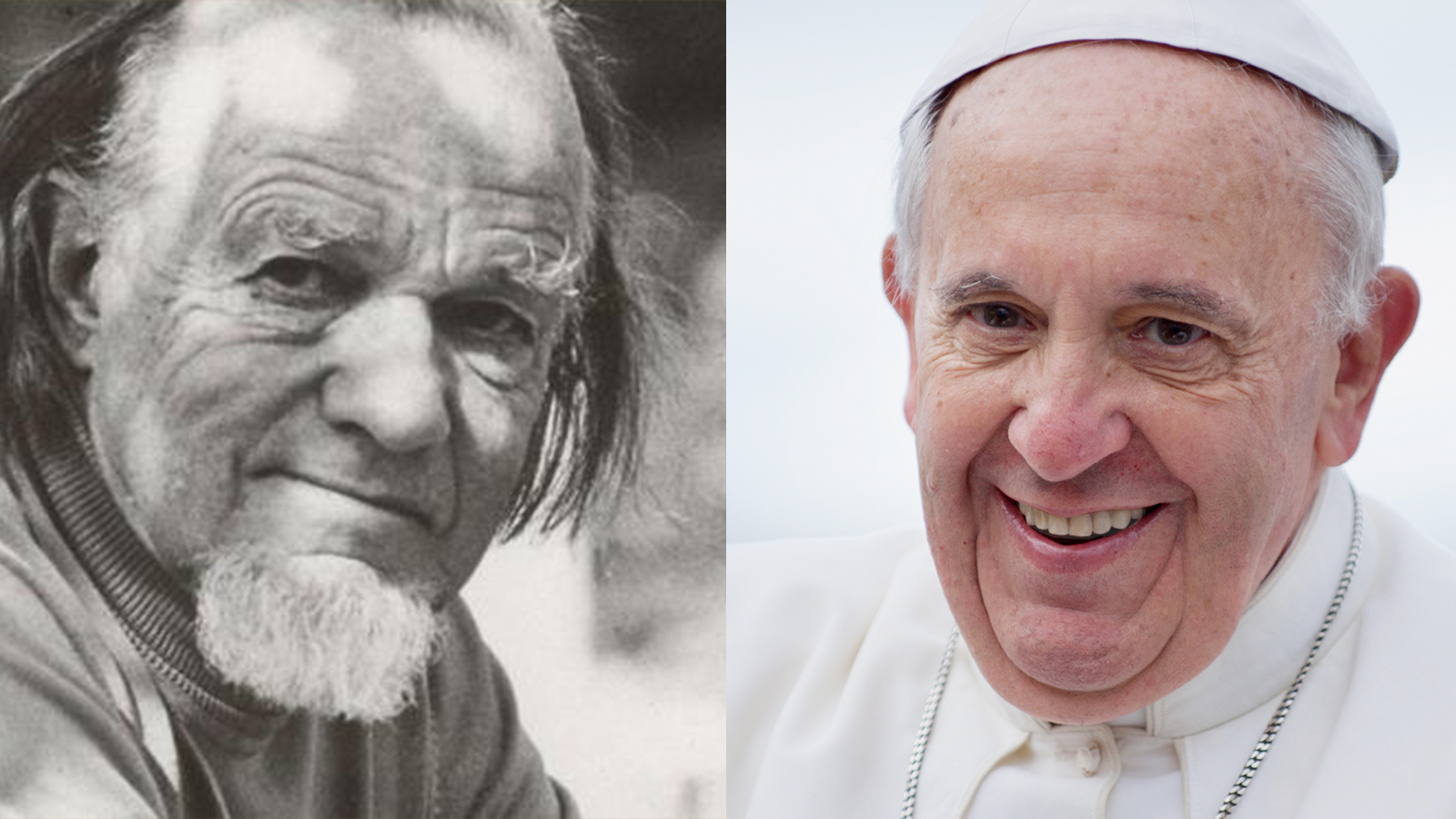

It begins, “What have they done to our fair sister?” If you have had a chance to skim the Vatican’s latest offering, you might understandably think you know from what I am quoting. After all, in Laudato Si’ (Praise Be to You) the second sentence introduces us to “our Sister, Mother Earth” and the third reads, “This sister cries out to us because of the harm we have inflicted on her.” Yet my opening words come not from the pope, but from another Francis—Francis Schaeffer. They initiate what one might well call an evangelical encyclical on the care of our common home. Pollution and the Death of Man was published in 1970 and has remained in print ever since, and in light of the recent missive from Rome, it is well worth reading again.

At the start of his lengthy exploration of humanity’s relationship in, to, and with God’s creation, Francis the pope quotes from the 13th-century Canticle of the Creatures written by his papal namesake hailing from Assisi, Italy. True to his penchant for engaging with the contemporary culture of his time, Francis the Presbyterian minister from Germantown, Pennsylvania, was quoting from the Doors.

Evangelicals, of course, recognize no popes of our own and bestow no official spiritual laurels. But over a decade after his death in 1984, CT canonized, if you will, Schaeffer as “Our Saint Francis” in a 1997 cover package. In his 2008 book, biographer Barry Hankins said Schaeffer was “the most popular and influential American evangelical of his time in reshaping evangelical attitudes toward culture, helping to move evangelicals from separatism to engagement.” He popularized the idea of “worldview” thinking and was never afraid to look at the world as it actually was—praising the good, diagnosing the bad, and always pointing his wide ranging listeners to the cultural fullness found in Christ.

For decades, Francis and his wife, Edith, welcomed spiritual wanderers from the famous to the nameless into the shelter of their L’Abri retreat in the Swiss Alps. And from that unlikely perch, the goateed and knickerbockers-wearing Schaeffer wrote, lectured, and filmed his way to an unparalleled cultural influence within American evangelicalism. Only Billy Graham had a larger overall impact on this subculture in the latter half of the 20th century. But in the realm of politics, Schaeffer probably did more than Graham to shape the partisan coalitions that are still relevant today.

In the late 1970s and early ’80s, Schaeffer was the key figure organizing evangelical opposition to abortion and judicial overreach. Jerry Falwell Sr., whose Moral Majority organization was widely credited with helping elect President Ronald Reagan, said Schaeffer “pushed me into the arena and told me to put on the gloves.” Schaeffer also convinced Falwell and company to overcome a culture of isolation and tag team with Catholics and other “co-belligerents.” Schaeffer did not single-handedly make the Religious Right, but it is unlikely that it would have been made without him.

Caring for Our Fellow Creatures

Given the present inclination of religious conservatives towards environmental concerns—white evangelicals now consistently poll among the least concerned about such issues—it may strike some as odd that one of the first published works from the godfather of the Religious Right movement would center on matters green. Schaeffer, though, loved spending time outdoors; he mourned over human actions that marred nature’s beauty and he did not own a car for the final 36 years of his life. He was critical of philosophical elements within the then nascent environmental movement, but his solution was not the ostracism that is regularly practiced today. Instead, he called for the church to lead by example and stand as a “pilot plant” that demonstrated the “substantial healing” of creation that is possible in the here and now.

Schaeffer thought it key to maintain the dynamic tension between humanity’s uniqueness and our continuing connection to the rest of creation. Schaeffer worried that the pantheism motivating many of the millions that took to the streets on the first Earth Day—April 22, 1970—could reduce humans to “no more than grass.”

“If the West turns to pantheism to solve its ecological problems,” wrote Schaeffer, “the human will be even more reduced, and impersonal technology will reign even more securely.” He affirmed that as divine image-bearers, people were distinct from the rest of creation. But at the same time, he lamented that much of evangelical Christianity had adopted a dualistic view of the world that did not take nature seriously. For Schaeffer, there was more to life than just finding the road to heaven.

Schaeffer instead emphasized that our shared finiteness created a bond with the rest of creation. We should look on our “fellow creatures” with both a sense of responsibility and a sense of relatedness. In his book, Schaeffer highlighted a particular sect that had no qualms about beating its soulless farm animals and declared that they practiced a “perverted form” of Christianity.

There was a God-created hierarchy in play—a rock should be treated differently than a plant, and similarly a plant differently than an animal. All had intrinsic value to God, who retained full ownership. “Man’s dominion,” Schaeffer emphasized, “is under God’s dominion.” These creations had purposes that extended beyond providing pleasure to humans, and so, while our use was authorized, “we must not allow ourselves individually, nor our technology, to do everything we or it can do.”

Schaeffer railed against the ravages of “greed and haste” and warned that if we treat other people and creation as mere machines, then “we make ourselves machines” and “the wonder of humanity will begin to disappear.” He sadly saw much of the church around him practicing a form of “sub-Christianity,” and by doing so it forfeited a part of its calling as well as “an evangelistic opportunity.” This attitude partly explained to him why the church then appeared “irrelevant and helpless.”

I suspect that Schaeffer would find much to like in Laudato Si’. First, Schaeffer too was a great admirer of Francis of Assisi. He wrote,

Saint Francis’s use of the term “brothers to the birds” is not only theologically correct, but a thing to be intellectually thought of and practically practiced. More, it is to be psychologically felt as I face the tree, the bird, the ant. If this is what the Doors meant when they spoke of “our fair sister,” it would have been beautiful. Used correctly in the Christian framework, that expression is magnificent.

Moreover, Pope Francis shares with Schaeffer an appreciation for the multifaceted relationship between humanity and the rest of creation. Laudato Si’ notes the “infinite distance between God and the things of this world” and how, in such shared finiteness, all created things are “linked by unseen bonds and together form a kind of universal family.” In the next breath, however, Pope Francis rightly notes, “This is not to put all living beings on the same level nor to deprive human beings of their unique worth and the tremendous responsibility it entails.” Indeed, the pontiff decries “an obsession with denying any pre-eminence to the human person.” All of this tracks well with Schaeffer’s thought—as do the pope’s calls for recognizing beauty, limiting our use of technology, and placing other values before financial profit.

Both men also demonstrate, contrary to current American political expectations, that a care for the earth should dovetail with a care for people, especially the unborn. As the pope said, “A sense of deep communion with the rest of nature cannot be real if our hearts lack tenderness, compassion for our fellow human beings.” True concern for nature is, therefore, “incompatible” with justifications for abortion.

Toward the end of his encyclical, Pope Francis offers what sounds a bit like an evangelical altar call:

In calling to mind the figure of Saint Francis of Assisi, we come to realize that a healthy relationship with creation is one dimension of overall personal conversion, which entails the recognition of our errors, sins, faults, and failures, and leads to heartfelt repentance and desire to change.

What we need, said the pope, is an “‘ecological conversion’ whereby the effects of [our] encounter with Jesus Christ become evident in [our] relationship with the world around [us].” Schaeffer closes Pollution and the Death of Man with this exhortation: “[N]one of this will happen if it is only a gimmick. We have to be in the right relationship to him in the way he has provided, and then, as Christians, have and practice the Christian view of nature.”

I close by saying to both of them, “Amen, Francis!”

John Murdock is a natural resources attorney who writes from Texas. He helps direct Conservatives for Responsible Stewardship and the Earth Stewardship Alliance, and exists online at johnmurdock.org.