Three years ago, the Billy Graham Evangelistic Association (BGEA) shifted its focus to online evangelism. It laid off about 50 people—10 percent of its staff—and “redeployed resources to focus on areas of greater impact.”

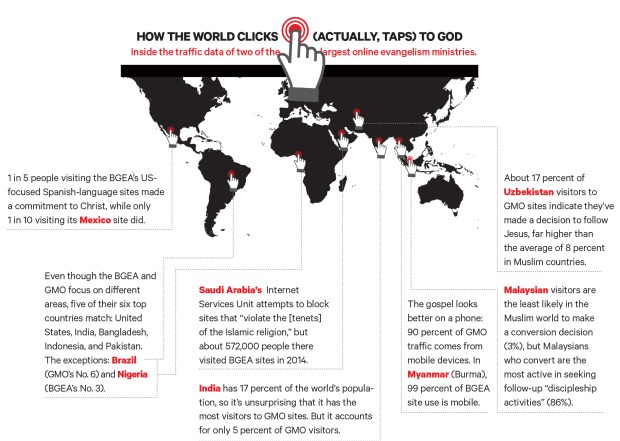

The change seems to be paying off. In 2014, the BGEA shared the gospel with almost 9.5 million people around the world. Of those, only about 180,000 were in a live audience at a crusade, while 7.5 million were reached through BGEA websites.

Of the 1.6 million people who told the BGEA they prayed “to accept Jesus Christ as [their] Savior” in 2014, less than 15,000 did so in person, while more than 1.5 million did so with the click of a mouse.

Since the BGEA launched its family of evangelistic websites—which include SearchForJesus.net and PeaceWithGod.net—less than 4 years ago, more than 5 million people have indicated a decision for Jesus.

More than 20,000 people view a gospel presentation every day, essentially “a crusade a day online,” said John Cass, the BGEA’s Internet evangelism director.

And the BGEA isn’t even the biggest kid on the block. Global Outreach Media (GMO), which began in 2004 as part of Campus Crusade for Christ (Cru) and spun off in 2011, reports more than 30 million online decisions for Jesus in 2014 out of 400 million viewed presentations across its 250 sites.

The numbers are mind-boggling—and accurate, said Michelle Diedrich, GMO’s chief marketing officer. “We have had our tracking and reporting verified and our systems audited. The great thing about the Internet is it’s all trackable.”

While some doubt that eternal salvation can be gained with the click of a button, it’s no different than raising your hand in church, Diedrich said.

Cass agrees. “If somebody’s responding to the gospel, we should assume God is doing a work in their life,” he said.

The biggest advantage to online evangelism is being able to engage people’s hearts anywhere, anytime, Cass said. The use of mobile phones has made it possible to connect with people even in the strictest of societies.

Evangelicals have been quicker to adopt online evangelism than the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, a group famous for its missionary zeal. Until April 2013, the Mormon church had strict rules on missionaries’ Internet use. Two months later, it announced “Facebook, blogs, email, and text messages” would be part of missionaries’ daily work. While door-to-door Mormon missionaries convert about 6 people during their 18- to 24-month service, online missionaries see about 30 converts in the same time.

It’s cheaper than door-to-door or mass evangelism, too. GMO spends less than five cents per gospel exposure. To put it in perspective: The latest calculations by the Center for the Study of Global Christianity show that, to baptize a convert in the United States, the Christian community spends more than $1.5 million. While some areas of the world are considerably cheaper—a convert in Tanzania costs about $2,500—nothing comes close to the cost efficiency of online outreach.

“Even if only 2 percent of the more than 135 million indicated decisions [since 2004] were long-term, with real spiritual transformation, I still haven’t seen anything that rivals that in terms of effectiveness,” Diedrich said.

The BGEA and GMO spend their dollars on display ads and search terms such as “Why doesn’t God answer prayer?” or “Why does God hate me?” Seekers who enter those phrases will see a link to a ministry page that answers the question and then points to a gospel presentation.

At the end of the BGEA’s four-step gospel presentation or video, visitors are given two buttons to click: “Yes, I’ve prayed the prayer” or “No, but I have a question.”

The process is neat. Maybe too neat, said Mary Schaller, president of Q Place, which operates small, local Bible studies—the antithesis of online evangelism.

“It can set up the false expectation that you have salvation” by clicking the right button, she said. “Belief is a regular and frequent turning toward Jesus, not a single event that guarantees your salvation.”

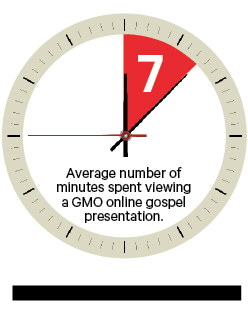

It’s also too quick, some say. The average time spent on a visit to a GMO website is about seven minutes, with visitors hitting just six pages.

“Is seven minutes enough time to enter into the momentous decision to follow Jesus in a wholehearted way?” said Richard Peace, an evangelism professor at Fuller Theological Seminary. “The impulse behind this reductionism is well intentioned. But it seems to me that the message may be so reduced that it is not really biblical.”

About 70 percent of conversions aren’t the result of a single event, but a journey of decisions, he said. “This is why evangelism is really a community process, not an online event.”

The lack of a physical presence can make online evangelism look like online education, said David Gustafson, a professor at Trinity Evangelical Divinity School. “There are real advantages in terms of delivery, but it’s primarily a transmission of information.”

Seekers also need physical role models and community, he said. A “hybrid model of delivery,” in which people find Jesus online but are directed to a real-life community, might be the best model going forward.

No online ministry disputes that. But moving responders to an online discipleship program or a real-life community is what Diedrich calls “the biggest challenge” for online evangelism.

Historically, GMO moves only 5 to 10 percent of its “indicated decisions” into “discipleship activities,” which include connecting with an online mentor or finding a local church.

“We can actually track from the time someone visits a site to when they get connected on the ground,” Diedrich said. “We hoped when we started this whole thing that there was some international organization to which we could say, ‘Okay, here you go!’ It’s been very regional instead.”

The close-knit culture of some regions, such as Brazil or Africa, makes the local connection easy, she said. Others, like China, are more difficult.

Making that connection depends in large part on the convert, and “one of the reasons people go to the Internet is because it’s anonymous,” Diedrich said.

At 2 a.m., she said, seekers will tell you anything. They communicate through email, chat, or Facebook messages with online missionaries, many of whom are retirees or Christian college students. During a partnership with Liberty University in 2013, GMO sites reached 2.4 million people in a single day, with Liberty students following up with new believers online.

But those encounters are by their nature more of a one-time conversation than a relationship. Of the 7.5 million who viewed the BGEA’s gospel presentation last year, fewer than 230,000 provided contact information for follow-up, Cass said.

By contrast, about 80 percent of those who come to a live event come with someone they know, which provides a support system, he said. (One-half to three-fourths of those who make decisions are rededications instead of first-time commitments, according to Graham biographer Grant Wacker.) When people come forward, the BGEA asks local churches to follow up with them and report back. The BGEA aims for a 90 to 95 percent response rate from churches, said Cass.

“Discipleship is nowhere near where we want it to be,” he said. Making the step from online to offline is “really where our heart ministry is. We want to see people connected relationally.”

Being sensitive to culture is one way to do that, he said. Another might be asking converts for the contact information of a believer that they know, so the organization could make the connection.

“True growth doesn’t come from clicking a button saying you’ve prayed a prayer, but from beginning to understand how God loves you,” Cass said. “Ultimately, we want to see people handed off to a local body of believers.”