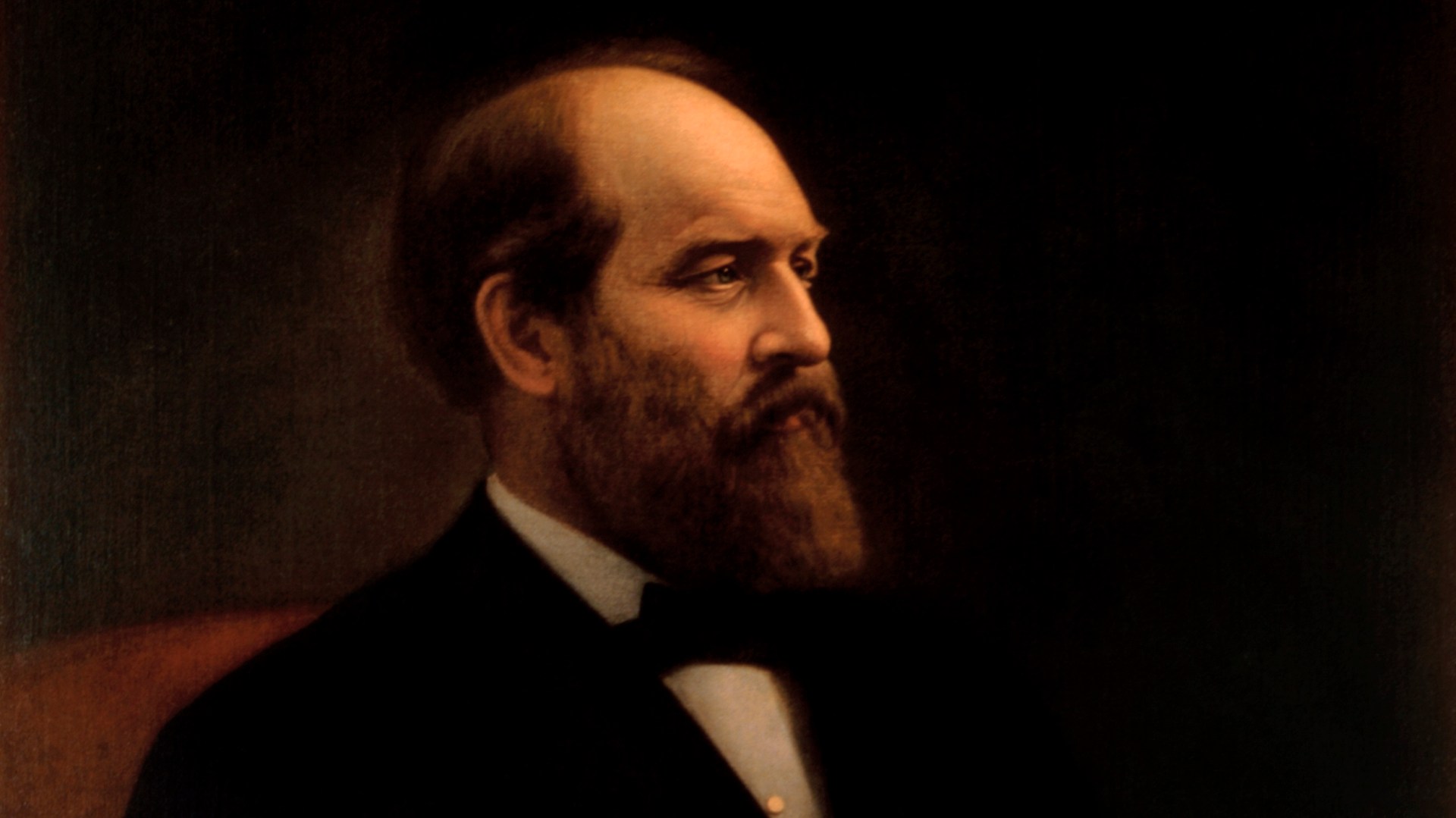

When most people hear the name "Garfield,” odds are that James Abram Garfield, the United States’ 20th president, doesn’t come to mind—if anything, they probably think of a certain orange cat who just hates Mondays. Beyond the fog of post-Civil War history, though, there are two surprising facts that make Garfield a person of note for ministry leaders: he was the only President to also serve as an ordained minister, and he never actually aspired to be President in the first place.

Garfield’s presidential candidacy came as a surprise even to himself. In 1880, he was selected to give the Republican National Convention stump speech for his fellow Ohioan and hopeful nominee John Sherman. Looking out at the contentious Chicago convention hall, Garfield started his speech by addressing the party's divisiveness: “This assemblage seems to be a human ocean in tempest . . . but I remember that it is not the billows, but the calm level of the sea, from which all heights and depths are measured.”

The audience was hypnotized. As Garfield settled into the rhythm of his speech, the tone of the room noticeably changed. After building the necessary lead-in for Sherman's nominating motion, Garfield’s voice rose: “What shall we do?”

Someone broke the silence with an unexpected shout: “Nominate Garfield!"

Shocked, Garfield demurred, trying to rebuild the momentum for Sherman. But the seed was planted. Despite Garfield's attempts to stop the stampede, the scales had decidedly shifted. On the thirty-sixth ballot, the humble man from Ohio found himself chosen by his party to run for the highest office in the land without ever giving consent. As the celebratory guns fired from Chicago's lakefront, Garfield excused himself, got in a carriage, and left the convention hall, trying to understand what had just happened. Whelmed by the weight of his impending influence, he went back to his modest hotel room, closed the door, and sat in silence.

Garfield’s modesty would make him seem wildly out of place in today's political arena, but it fits his role as a lay-minister well. Of the church leaders I’ve known, those who have contributed the most to those in their care have achieved their influence as a result of character that’s unseen and humility that’s steady. It’s never been done through declarative muscle; instead, like Garfield, they faithfully followed the humble path and have inspired others to do the same. They’re the pastors who hang around after everyone’s gone, get out the mop, and clean up red Kool-Aid stains in the church kitchen without thought of recompense or recognition. They’re the tired-but-tireless Sunday school teachers who are in their fifth decade of helping children understand what Jesus meant when he said, “Take up your cross and follow me.” They’re everywhere—but rarely rewarded. And that’s probably how they want things to be.

Garfield’s relative anonymity in history shouldn’t surprise us—an assassin’s bullet tragically ended his life less than seven months into his term. His legacy, however, is important because his story relates an enduring lesson: true, dignified influence is often achieved not through force or compulsion, but through quiet humility.

Recommended for further reading:

The Destiny of the Republic by Candice Millard Dark Horse by Kenneth Ackerman