I’ve come to this café often enough now to have a favorite table and a nodding relationship with a few regulars. I chose it because it’s on a main street downtown—locals filter in and out each day, ordering their favorites, talking, and laughing.

I committed to coming here every day and praying a simple prayer: to ask God to reveal his longing for this neighborhood. I’ve stuck to this commitment most days, watching what’s going on around me, waiting to hear from God.

But some days, it’s easier to scroll through Facebook than to study humans and God and try to figure out how they might come together.

Today I’m attempting to read Jeremiah. But the young woman at the next table is more interesting. She’s often here, chatting with friends or reading alone. Today she seems to be sketching, her pencil scratching away at loops and lines. From what I’ve picked up in overhearing her various conversations, she’s a thoughtful person: kind in offering her opinions, interested in important issues but quick to draw out the insights of her friends. She reads poetry and politics. Her yellow cardigan is hand-knitted—I assume it has an interesting story.

I make guesses about her career path. Maybe she’s an artist of some kind, but she makes ends meet with more practical—but still meaningful—work.

I might have chosen a life like that if I hadn’t gone to seminary. But I did go to seminary, and now I find myself here, studying the community and praying about a church plant.

I wonder what this woman would think if she knew my plans. Would she think I’m weird, assume I’m judgmental? I wouldn’t blame her. I have the same assumptions about church people sometimes.

I turn back to Jeremiah and begin to read: “Then, just as the Lord had said, my cousin Hanamel came to me in the courtyard of the guard and said, ‘Buy my field at Anathoth in the territory of Benjamin.’”

I look back at the woman next to me. What interest could she possibly have in a field at Anathoth?

Am I even interested in a field at Anathoth? It might take some effort.

I look at Jeremiah again and let my yearning flow out to God. If there were words, they would be something like: “It’s hard enough to understand the Bible, to understand this neighborhood, and to understand myself. Finding a way for them to come together seems impossible.”

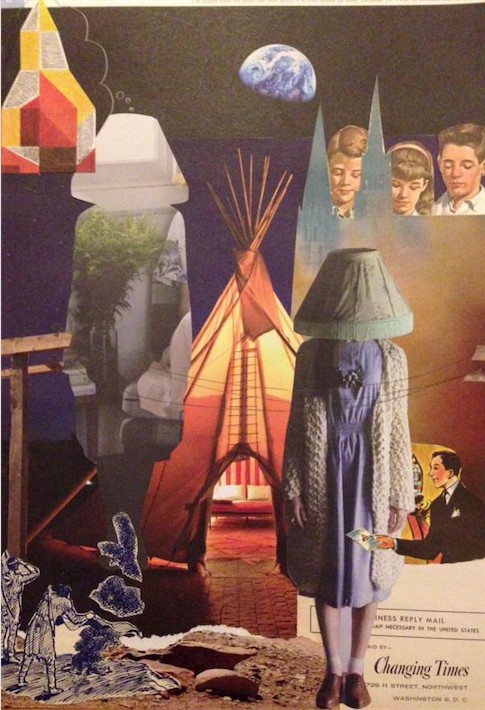

As I hang my head, longing leads me into imagining, imagining draws me into dreaming. The walls and roof of the café fall away—yet I’m still in the café.

The girl in the cardigan is still here, too. I find myself wanting her to like me, hoping she’ll notice my vintage shoes. It’s only now that I see she has a lampshade on her head.

Does she need help? She seems quite comfortable, standing still as a post. She obviously doesn’t want to be disturbed.

This is obvious to me but not to the man in the suit who’s trying to hand her a tract. She’s really not interested. I wish he’d just go away, but he stands there still, smiling awkwardly, holding it out for her to take. It’s easy for her to ignore him with a lampshade on her head.

For the first time, I notice a cathedral sitting behind her—one of the big, European ones. Ancient and glorious, but a long way off in miles and years. Between the spires of the cathedral, a choir of children sings in perfect harmonies: their Latin pronunciation flawless, their eyes directed ever so condescendingly at her.

Still, the girl is uninterested. Or maybe she’s not even aware of their efforts.

But now my eyes are drawn to a growing cloud of smoke. Behind the billows, I see an angel, flapping over the smoke, shaping clouds into signals. He watches the girl in hope that she will notice the efforts he’s making for her sake. But she can’t see the cloud he’s shaping, doesn’t know how much it looks like her. I will her to look, to see the strange plant growing within the smoke version of herself, a plant that is hopeful but not yet fully formed.

The smoke girl grows. In some ways, she seems more real than her human counterpart, so filled with the potential for life. This smoke girl’s dreams float over her head—visions of a strange, colorful church. It has a steeple, but the walls sway with color as if painted by Picasso. It’s hard to say what shape it takes as it pulses with life. Is it new for the sake of new? Cool for the sake of cool? Or is it something real and lasting? It has more life than the cathedral, more hope than the tract. I want to watch and see what her dream will become.

As I wait on all that’s growing, I begin to take in what is happening beneath and behind it all. The setting of this whole tableau is a desert. But there, not so far away, is an inviting scene: a huge tent has been built. Is it a revival tent? A tabernacle in the desert? I don’t know, but it stands empty and unnoticed.

It is filled with light. And the door flaps are tied back, open wide, ready for all who will come. Is that music I hear, inviting us in? Why is no one coming? Does anyone else see it? Does anyone else hear the music? Is that Leonard Cohen, singing “Hallelujah” over us all?

The drifting chords draw me out of my dream and back into a busy café on a Tuesday afternoon. The cash register rings; the door opens to admit a new customer.

Was it a prayer, a dream, or a vision? All I know is it grew from my longing. And from it, my longing is clearer: I long for a native expression of church, something that doesn’t feel so many steps away from this moment, this café, this girl in her yellow cardigan.

I long to find an expression of faith that grows from this ground, responds to the questions this community is asking. I wish “church” didn’t bring to mind 1950s evangelism, European feudalism, and a million other negative images. I long for Scripture to speak directly to the hurts and issues and questions of this moment and this place.

What can it mean to be a missionary to my own people?

What does it mean to see these people as my own when I feel like a missionary?

I snap myself back to the present moment. I am sitting in a café, reading Jeremiah.

The story of buying fields continues. God instructs Jeremiah to buy a field in his hometown, even though the siege barricades are against the walls and the people of Israel are about to be dragged into exile in Babylon. To spend the money now, to invest in the land of his fathers, to seal up the deed and store it away: it seems like the least realistic use of his time and money.

But God has chosen to use Jeremiah’s life as a place to reveal his promises to his people. Jeremiah allows his life to be used as a story of God’s faithfulness. He invests in a real place with an eye toward what God has in store.

Whatever my work will become, it will grow from that kind of life.

For now, I look over and share a sheepish smile with the girl in the yellow cardigan.