On remote Breueh Island, northern Sumatra, lie two fishing villages, Lhoh and Lampuyang, which serve as home to local fishermen. Lhoh faces west on the island’s inlet. Lampuyang is on the other side, much closer to the island’s mountains. Lhoh is smaller and is known for its popular coffee shop. Lampuyang is larger, richer, and has a vibrant downtown and the local mosque.

Stories of fishing adventures were being swapped the late December morning that a massive earthquake shook the region. Minutes later, a Lhoh villager shouted, “The water is disappearing!” The quake had moved thousands of square miles of ocean bottom to the east, triggering three gigantic waves—a tsunami of frightening proportions.

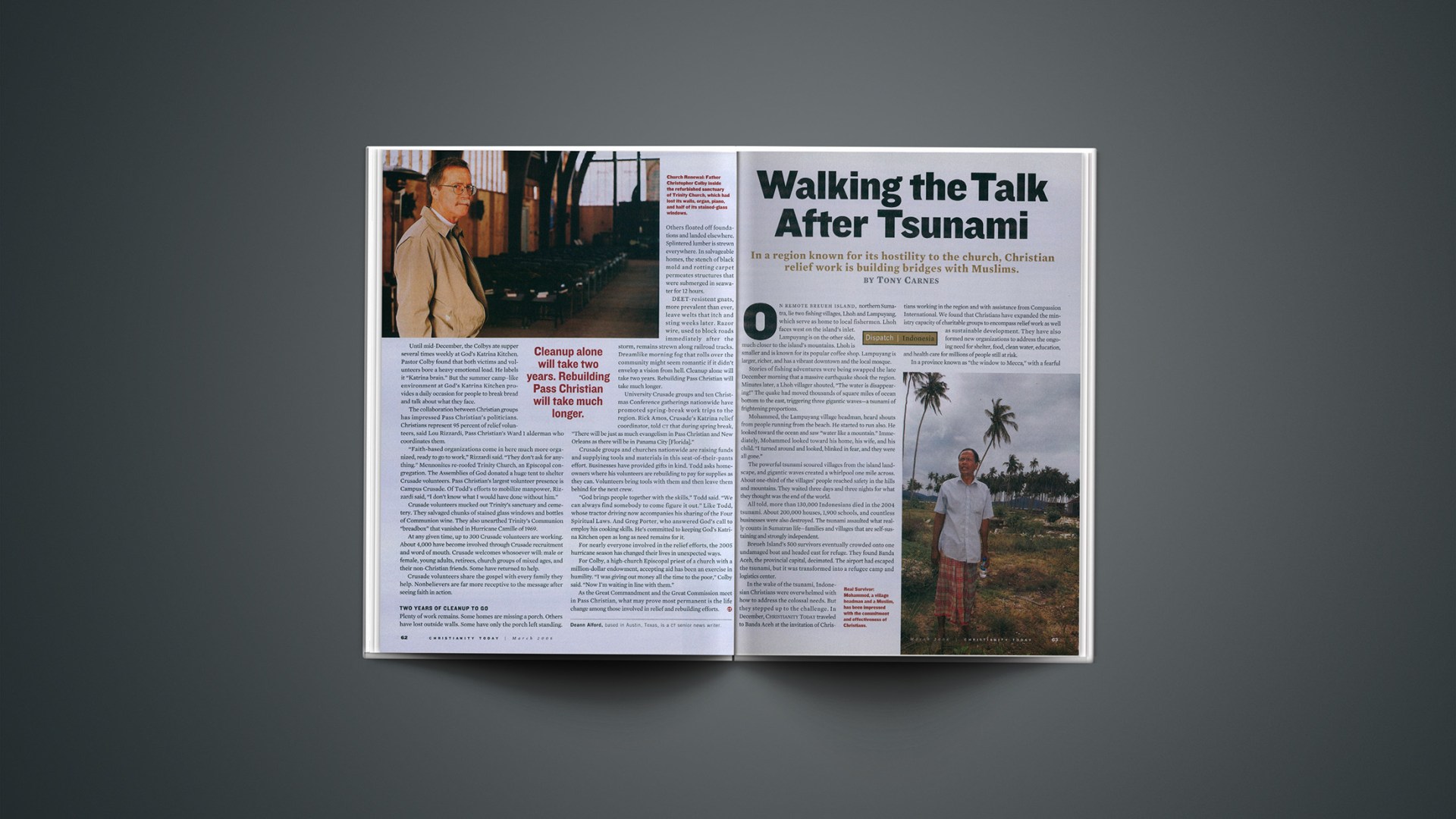

Mohammed, the Lampuyang village headman, heard shouts from people running from the beach. He started to run also. He looked toward the ocean and saw “water like a mountain.” Immediately, Mohammed looked toward his home, his wife, and his child. “I turned around and looked, blinked in fear, and they were all gone.”

The powerful tsunami scoured villages from the island landscape, and gigantic waves created a whirlpool one mile across. About one-third of the villages’ people reached safety in the hills and mountains. They waited three days and three nights for what they thought was the end of the world.

All told, more than 130,000 Indonesians died in the 2004 tsunami. About 200,000 houses, 1,900 schools, and countless businesses were also destroyed. The tsunami assaulted what really counts in Sumatran life—families and villages that are self-sustaining and strongly independent.

Breueh Island’s 500 survivors eventually crowded onto one undamaged boat and headed east for refuge. They found Banda Aceh, the provincial capital, decimated. The airport had escaped the tsunami, but it was transformed into a refugee camp and logistics center.

In the wake of the tsunami, Indonesian Christians were overwhelmed with how to address the colossal needs. But they stepped up to the challenge. In December, Christianity Today traveled to Banda Aceh at the invitation of Christians working in the region and with assistance from Compassion International. We found that Christians have expanded the ministry capacity of charitable groups to encompass relief work as well as sustainable development. They have also formed new organizations to address the ongoing need for shelter, food, clean water, education, and health care for millions of people still at risk.

In a province known as “the window to Mecca,” with a fearful reputation due to radical Islamist and rebel violence, this newfound commitment to relief work is earning Christians respect within the Muslim community.

The tsunami also spurred immediate and impressive political change. Desperation threw together an odd alliance. The Indonesian government, the rebel separatist group GAM (“Free Aceh Movement”), Western governments, and faith-based ministries all determined to seize every opportunity to ease tensions. The government and GAM militants struck a truce. More than 700 nongovernmental organizations piled into Sumatra in a ministry free-for-all unlike any seen since the fall of the Berlin Wall and the Soviet Union.

Innovations

Evangelical groups included both familiar and lesser-known relief agencies, many inexperienced in emergency relief. Banda Aceh was largely unknown in Christian missions circles, because the government had forbidden missionaries to work there due to radical Islam. Yet these groups stretched beyond their comfort zones in providing innovative support:

- Compassion International, a child sponsorship agency, helped to build houses.

- Samaritan’s Purse, skilled in medical intervention and housing, assisted in rebuilding fishing boats.

- Mission Aviation Fellowship, renowned for helping missionaries to remote locales, flew in relief supplies for the government.

Governments, agencies, and individuals pledged a record total of $13.6 billion in aid. The aid cleaned up tons of debris, restored schools by the thousands, prevented outbreaks of disease, restarted tens of thousands of businesses, and provided thousands of homes.

Bambang Budijanto of Hong Kong was among the first Christians to arrive in Banda Aceh from the outside. During the previous five years, Bambang had rescued the Indonesian office of Compassion from the brink of bankruptcy. As a result of this effort, he was put in charge of all Asian operations and relocated to Hong Kong. Now his heart was aching for his home country.

Bambang is part of a new generation of Indonesian Christian leaders educated in the West and committed to democracy. He returned to Asia after completing his doctorate in development work, specializing in Muslim villages. He challenged his Christian friends to live and teach in Muslim villages. They formed a ministry called Pesat to improve the welfare of Muslims and promote religious tolerance, partnering with Compassion in Banda Aceh.

After the tsunami, Bambang realized that he could put to the test all he had learned about relational outreach to Muslims. After Bambang met the village headman, Mohammed, and toured Breueh Island with him, Mohammed was impressed. Here was a Christian man willing to spend the night in a place that even government officials were afraid to visit.

On the boat ride and over a dinner of sardines, rice, carrots, and cabbage, Bambang and Mohammed got to know each other better. But government officials inadvertently interrupted this budding friendship. They assigned Bambang to help Lhoh, Breueh’s smaller village, and another group to help Lampuyang.

Unprecedented Invitation

Housing is one of the most vexing problems after many major disasters, including the Asian tsunami. More than 67,000 Acehnese still huddle in tents. Most of the rest live in shelters, not homes. Much money for housing has been raised, but little has been spent. The American Red Cross, for instance, received $568 million but spent only $110 million in the six months after the tsunami.

Aceh officials are getting impatient. They say they will soon kick out groups that have failed to fulfill their promises. Kuntoro Mangkusubroto, head of reconstruction for the region, told CT that he plans on moving every refugee from tents and temporary barracks into permanent homes by the end of this year. But frustrations are running high. Mohammed is not alone in saying, “All we get are promises, promises.”

While the organization working in Lampuyang has asked for three more years to rebuild homes, Bambang’s team finished rebuilding Lhoh by December. Kuntoro points to Bambang’s outreach as an example of what others should do. Keeping promises and building bridges to Muslim communities, Kuntoro said, will create “an open, progressive society.” But Kuntoro warned, “Other [agencies] are not even building yet. I want to know why.”

Bambang’s example is one reason Muslims and Christians met in Lampuyang at a gathering of village elders to talk about working together longterm.

In recent months, fundamentalist Muslims had attempted to get Christian ministry teams kicked out of Banda Aceh. But Mohammed considers Bambang a part of Lampuyang. The headman even taught Bambang a few secret fishing techniques.

So in December, Mohammed opened the village meeting by saying with a commanding voice, “The other ngo says it will take three years to rebuild Lampuyang. We need more food to come to this village, not to Lhoh.” Mohammed set forth a risky idea: Christians should rebuild Lampuyang. He had seen 240 houses go up in Lhoh and other villages under Bambang’s management, while Mohammed’s much larger and more prestigious village remained mostly empty.

On the other hand, Bambang knew better than to let Mohammed rush him into a commitment against the wishes of the government. He faced a dilemma of success. He had kept his word about rebuilding Lhoh, formed a deep friendship with Mohammed, and now his friend wanted him to help rebuild Lampuyang and also build a kindergarten with Christian teachers. That request would have been unthinkable before the tsunami. In fact, a highly placed political source told CT that a fundamentalist faction within Indonesia’s government will still attempt to force local Muslim leaders to sever all ties with Christian charities sometime this year.

Bambang could neither refuse to help, nor take over. So he offered to secure more food, help with fishing boats, and build roofs. And he said, “We will try to build you 20 houses. But our workplace is at Lhoh, not here.”

Mohammed sighed over the constraints of the situation. “I desperately want your help to come to my village.” At the meeting, someone suggested the government could help. Mohammed laughed. “The government help? Many people say they want to help out, but few actually help. They all make promises, but we are stuck here.”

Talking further, the Lampuyang council, comprised entirely of Muslims, committed the village to working with Christians.

Afterward, Bambang reflected on Mohammed: “He is a man of dignity. Previously, people came to him for help. Now he depends on people.”

For local Indonesian Christians, their worst nightmare of Islamic aggression has temporarily faded away in light of the village’s commitment. Bambang said at first local Christians thought they would become martyrs in Banda Aceh. “We have discovered that Banda Aceh people are not so bad,” he said. “We now live in each other’s minds. Grace can walk through open doors.”

Tony Carnes is a senior writer for CT.

Copyright © 2006 Christianity Today. Click for reprint information.

Related Elsewhere:

Yesterday we posted an update on ministry after Hurricane Katrina.

Our full tsunami coverage is collected on our website.