| • |

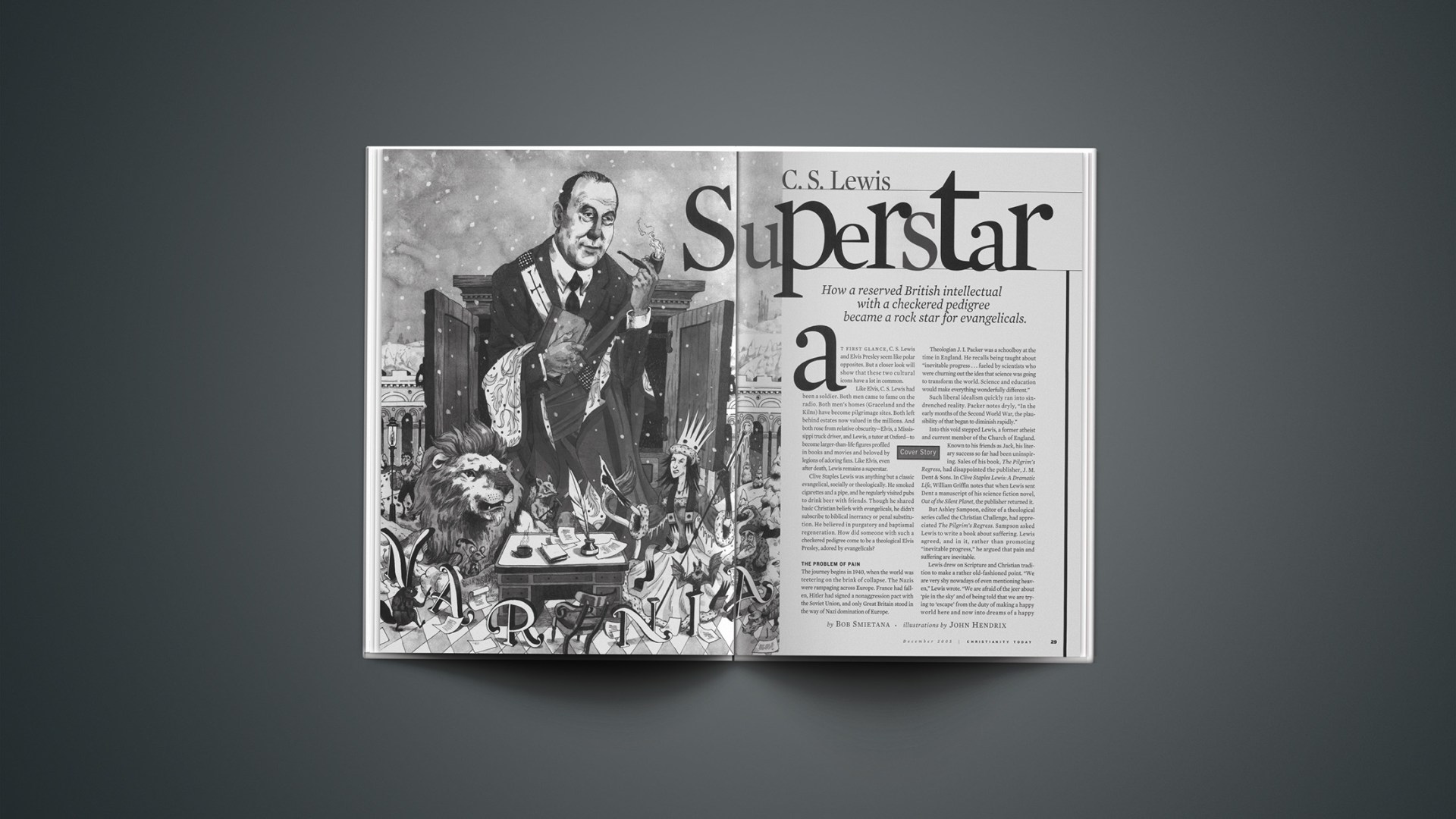

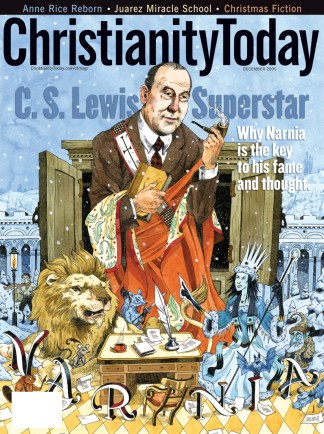

At first glance, C. S. Lewis and Elvis Presley seem like polar opposites. But a closer look will show that these two cultural icons have a lot in common.

Like Elvis, C. S. Lewis had been a soldier. Both men came to fame on the radio. Both men’s homes (Graceland and the Kilns) have become pilgrimage sites. Both left behind estates now valued in the millions. And both rose from relative obscurity—Elvis, a Mississippi truck driver, and Lewis, a tutor at Oxford—to become larger-than-life figures profiled in books and movies and beloved by legions of adoring fans. Like Elvis, even after death, Lewis remains a superstar.

Clive Staples Lewis was anything but a classic evangelical, socially or theologically. He smoked cigarettes and a pipe, and he regularly visited pubs to drink beer with friends. Though he shared basic Christian beliefs with evangelicals, he didn’t subscribe to biblical inerrancy or penal substitution. He believed in purgatory and baptismal regeneration. How did someone with such a checkered pedigree come to be a theological Elvis Presley, adored by evangelicals?

The Problem of Pain

The journey begins in 1940, when the world was teetering on the brink of collapse. The Nazis were rampaging across Europe. France had fallen, Hitler had signed a nonaggression pact with the Soviet Union, and only Great Britain stood in the way of Nazi domination of Europe.

Theologian J. I. Packer was a schoolboy at the time in England. He recalls being taught about “inevitable progress … fueled by scientists who were churning out the idea that science was going to transform the world. Science and education would make everything wonderfully different.”

Such liberal idealism quickly ran into sin-drenched reality. Packer notes dryly, “In the early months of the Second World War, the plausibility of that began to diminish rapidly.”

Into this void stepped Lewis, a former atheist and current member of the Church of England. Known to his friends as Jack, his literary success so far had been uninspiring. Sales of his book, The Pilgrim’s Regress, had disappointed the publisher, J. M. Dent & Sons. In Clive Staples Lewis: A Dramatic Life, William Griffin notes that when Lewis sent Dent a manuscript of his science fiction novel, Out of the Silent Planet, the publisher returned it.

But Ashley Sampson, editor of a theological series called the Christian Challenge, had appreciated The Pilgrim’s Regress. Sampson asked Lewis to write a book about suffering. Lewis agreed, and in it, rather than promoting “inevitable progress,” he argued that pain and suffering are inevitable.

Lewis drew on Scripture and Christian tradition to make a rather old-fashioned point. “We are very shy nowadays of even mentioning heaven,” Lewis wrote. “We are afraid of the jeer about ‘pie in the sky’ and of being told that we are trying to ‘escape’ from the duty of making a happy world here and now into dreams of a happy world elsewhere. But either there is ‘pie in the sky,’ or there is not. If there is not, then Christianity is false, for this doctrine is written into its whole fabric. If there is, then this truth, like any other, must be faced, whether it is useful at political meetings or not.”

On the Radio

The Problem of Pain became Lewis’s first publishing success. Soon after its release, Lewis received a letter from J. W. Welch, head of religious programming at the BBC. Would Lewis consider recording a series?

The idea astounded Lewis, who, Griffin notes, “hardly listened to the radio and could not remember having heard a religious program.” Welch suggested two options: a series about Christian influence on modern literature or “a positive restatement of Christian doctrines in lay language.” The second appealed to Lewis. He wrote to Welch, telling him he would be glad to help, provided the programs could wait until the summer holidays.

In August 1941, Lewis began a series of four 15-minute programs for the BBC, with the assistance of a Presbyterian minister named Eric Fenn. The first series, “Right and Wrong: A Clue to the Meaning of the Universe,” was followed by talks on “What Christians Believe” and “Christian Behavior.” The three series would form the basis for Lewis’s masterwork of apologetics, Mere Christianity. He would appear 29 times on the radio, each with an estimated audience of 600,000 people.

The radio talks had to be brief, precisely scripted, approved by BBC censors, and then followed to the letter. Any unexpected pauses, as Justin Phillips pointed out in C. S. Lewis at the BBC, could have allowed the signal to be interrupted by the German propagandist “Lord Haw-Haw,” broadcasting on the same frequency. Fenn coached Lewis in the art of writing for radio. This skill sharpened Lewis’s writing, says Walter Hooper, Lewis’s literary executor. “Lewis was born with a talent for clarity and impatience with vagueness,” he writes, “but the BBC’s contribution was requiring Lewis to write short, crisp sentences, each of which made a precise contribution to Christian theology.”

The talks made Lewis a household name in Britain, says Christopher Mitchell, director of the Marion E. Wade Center at Wheaton College. “With the exception of Churchill,” Mitchell says, “Lewis was the most recognizable voice in Britain.”

Jerry Root, assistant professor of evangelism at Wheaton College, says that Lewis’s academic credentials gave him “some credibility right off the bat.” Also, Lewis had something to say when the opportunity came to him. “This wasn’t a guy who fumbled when the spotlight shined on him,” says Root.

Lewis’s popularity grew through another technological innovation. “His books came out at a time when trade paperbacks were becoming popular,” Root says. “Consequently, they were disseminated easily because he already had a [built-in] audience from the radio.”

Concurrently with the broadcast talks, The Guardian, a Church of England newspaper, began running another of Lewis’s literary inventions—a series of fictional letters from Screwtape, a senior devil, to his nephew, an entry-level tempter named Wormwood. The letters ran once a week from May to November 1941. Lewis’s payment: £62.

When they were published in book form in the spring of 1942, The Screwtape Letters became an instant success. From 1941 to 1947, readers in the United Kingdom and the United States bought a million copies of Lewis’s books, propelling him all the way to the December 1947 cover of Time magazine.

The timeliness of Lewis’s message was matched by his clarity as a writer.

“You can’t impact people if they don’t know what you are saying,” says Mitchell. “Lewis had just remarkable instincts about what to address and what not to address and how to address it.”

In his fiction, especially The Chronicles of Narnia, Mitchell says, Lewis was subtler in his presentation of Christianity and talked about “smuggling the gospel past watchful dragons.” In his apologetics, Lewis dispensed with subtlety. “He was not trying to be clever,” Mitchell says. “He was not trying to engage in a nonoffensive way or leave some measure of ambiguity. He was not concerned about putting people off. He was concerned about communicating as clearly and as forcefully as he could what Christians really do say.”

The writers and editors at Time in the 1940s and ’50s seemed captivated by Lewis, running eight substantial articles on him from 1943 to 1958. These included reviews of The Screwtape Letters (1943), Christian Behavior (1944), The Great Divorce (1946), Surprised by Joy (1956), and Till We Have Faces (1957), as well as a cover story, “Don Versus Devil” (1947), a story on Lewis’s first lecture as professor of medieval and Renaissance English literature at Cambridge (1958), and a recap of an essay Lewis wrote for The Christian Herald on faith and outer space.

The stories in Time are nearly unanimous in their praise. “Men who can write readable books about religion are almost as rare as saints. One such rarity is the Oxford don, Clive Staples Lewis,” wrote the reviewer of The Great Divorce.

“He would be the last to claim that what he says is new, but, like another eloquent and witty popularizer of Christianity, the late G. K. Chesterton, he has a talent for putting old-fashioned truths into a modern idiom,” the author of “Don Versus Devil” wrote. “With erudition, good humor, and skill, Lewis is writing about religion for a generation of religion-hungry readers brought up on a diet of scientific jargon and Freudian clichés.”

Narnia

The one area Time ignored was Narnia. These books came out once a year from 1950 to 1956, again making Lewis a household name, says Packer. “Lots of people who weren’t Christians loved the Narnia stories,” he says. “They sold enormously from the start, and they really put him on the map in England and in the States. Previously, he’d just been one of the better-known Christian writers among those who read Christian writers, which wasn’t the majority of the population.”

The strange thing about the Narnia books is that Lewis never had children. According to his biographers, he was never particularly fond of them, either. But he had a rare ability to give “imaginative body to Christian doctrine,” says Mitchell.

The Chronicles also shaped Lewis’s legacy, says James Como, author of Branches to Heaven: the Geniuses of C. S. Lewis: “Lewis’s repute these days … very often radiates out from Narnia. Once Narnia hit, there seemed to be a focus on a certain Lewis—the children’s writer, the man of enormous imagination—and we get this second wind of rock stardom that goes on through the 1950s.”

During this period, Lewis began to build relationships with American evangelicals. In 1953, Clyde Kilby, professor of English at Wheaton, visited Lewis at Oxford, and the two began corresponding. Two years later, Carl Henry, the first editor of Christianity Today, contacted Lewis about contributing to the magazine. Lewis declined but wished Henry well.

Lewis did appear in the magazine’s pages several times during its first five years. The first time was in 1958 in Kilby’s article, “C. S. Lewis and His Critics,” which defended Lewis against a critique by W. Norman Pittinger in the Christian Century. Lewis’s orthodoxy and the straightforward approach of his writing bothered Pittinger.

“In all my reading of Lewis,” Kilby wrote, “I think one of his best qualities is his avoidance of technically theological language. It is the very thing which has made him spiritually thrilling to thousands of people around the world.”

Mitchell says that Lewis appealed to evangelicals because his conversion was so much like their own. “He had an evangelical experience, this personal encounter with the God of the universe.”

Speaking about Surprised by Joy, Lewis’s spiritual autobiography, Mitchell adds, “Lewis takes the entire book to get to theism and unpacks it carefully, but his actual movement to Christ happens in about two or three sentences. That is all he says. At the end of the day, Lewis believed that in Christianity you are confronted with a person that you either say yes to or no to … and that is very evangelical.”

Lewis’s standing as an intellectual also appealed to evangelicals, because so few academics gave Christianity much credence. “He came along at a time when the assumption was we had basically gotten rid of Christianity, that no one took it seriously,” says Mitchell.

Banking the Coals

As he grew older, Lewis feared that he would be “one of those men who was a famous writer in his forties and dies alone.” While those fears never came to pass, his writing fell out of fashion in the 1960s, says Como, and sales of his books slowed. “Honest to God comes out, and the ’60s happened,” Como says. Lewis was no longer seen as relevant. When Lewis died on Friday, November 22, 1963, the same day that JFK and Aldous Huxley died, it appeared that his influence on the broader culture would fade. In the next decade, the civil rights movement, Vietnam, and the drug and sexual revolutions thrust aside interest in classic apologetics or children’s literature for many readers.

But under the cultural radar, a number of critical things were happening.

First, “the indefatigable and indispensable Walter Hooper was at work, editing Lewis’s unpublished works,” says Como. Hooper, who became literary executor of the Lewis estate, began compiling Lewis’s articles, letters, sermons, and other material into book form and negotiating with a new publisher, Collins Publishers.

“My primary job was to edit new Lewis books and make sure the publishers kept Lewis’s other books in print,” Hooper told CT. “I made it clear that Collins would get a new Lewis book on the condition they reprinted two books that had gone out of print. It was tough going at first, but eventually they understood that Lewis would be around for a long time.”

Consequently, though his books were not at the forefront of cultural conversation, thousands still had ready access.

Meanwhile, at Wheaton College, Kilby compiled A Mind Awake, the first anthology of Lewis’s work. He also began collecting Lewis’s books and papers, a collection now housed at the Marion E. Wade Center at Wheaton. Kilby, says Como, was “planting seeds and keeping the coals burning”—passing Lewis on to a new generation of readers.

In 1969, devotees organized the New York C. S. Lewis Society, the first of its kind. Others soon followed, creating a network where devotees of Lewis could congregate and discuss his work. Como, one of the founders of the New York society, says these groups provided a way to pass on Lewis’s legacy. “They had read Lewis in the 1940s and 1950s, and they started to remind those of us who were younger how great this man was,” Como says.

The real heroes, says Douglas Gresham, C. S. Lewis’s stepson, are parents.

“The children who first read The Chronicles of Narnia and loved them have read them to their children, and those children are now reading them to their children,” Gresham told CT. “This starts youngsters off with an appreciation of literature, and they will turn to Jack’s more grownup works later in life.”

During the early 1970s, popular Christian authors such as apologist Josh McDowell and the newly converted Chuck Colson wove Lewis’s works into their own. McDowell, in his book Evidence that Demands a Verdict, made use of Lewis’s famous description of Jesus as “liar, lunatic, or Lord.”

Thin Places

This was an era of renewed interest in the life of the mind among Christian college students, the era of Paul Little’s apologetic works and John Stott’s classic, Basic Christianity. On college campuses, Lewis’s books had a “profound impact” for decades on InterVarsity Christian Fellowship (IVCF), says Bob Fryling, the executive director of InterVarsity Press. Lewis’s books were (and still are) read by Christian students and others curious about the faith. ivcf used Lewis at evangelistic discussions in college dorms. “Outside of the Scriptures themselves, Lewis is probably the greatest authority and example of a thoughtful Christian faith,” says Fryling.

By 1977, Lewis’s books were selling 2 million copies a year. Once again, he was on his way to stardom. Seven years later, Lewis was back on the BBC, this time portrayed by actor Joss Ackland in Shadowlands, a film about Lewis’s romance with Joy Davidman Gresham. Soon after, the BBC broadcasted a live-action version of The Lion, the Witch and the Wardrobe.

By the late 1980s, Lewis seemed to be popping up everywhere, even in Tom Wolfe’s The Bonfire of the Vanities. Phyllis Tickle, an author and former religion editor for Publishers Weekly, recalls that in the early 1990s, Lewis’s books began to appear on the religion bestseller lists of secular bookstores. This trend continued after the Hollywood version of Shadowlands, starring Anthony Hopkins and Debra Winger, was released in 1994. According to Gary Ink, librarian at Publishers Weekly, Mere Christianity has been on the religion bestseller list ever since. According to Harper Collins, Lewis’s publisher, sales of his books have increased 125 percent since 2001.

Part of Lewis’s current appeal, says Tickle, is a postmodern interest in “thin places”—places where the physical world and the spiritual world meet—and for myth that makes sense of life in a way that rational thinking can’t. For their dose of myth, postmoderns turn to The Matrix, The Lord of the Rings, Star Wars, Harry Potter, and, of course, Narnia.

“Fantasy allows you to explain and grasp and integrate into your life things that are not logical,” she says. “Which is not to say that we’re fantasizing about our lives. It is to say that we can tell each other truth in story.”

Though Lewis’s reputation was revived through his apologetic works, currently (as in the 1950s) his imaginative literature is capturing the attention of evangelicals and others in this latest phase of his rock-star-like popularity. The Hollywood release of The Lion, The Witch and The Wardrobe is playing no small part.

The Question of God

In the 1940s, Lewis wrote about God to a generation “raised on Freudian clichés.” In 2004, he took on Freud himself—in a PBS series called “The Question of God.” The series was based on a more substantive book by Armand Nicholi, a Harvard psychiatrist who had for 35 years been exploring the meaning of life with his students through Freud and Lewis.

“Who would have guessed,” Como asks, “that Sigmund Freud—one of the intellectual giants of the 20th century—would now be seen on equal footing with C. S. Lewis?”

Hollywood is certainly convinced that Lewis is hot. How long he remains so will depend on the box office take of The Lion, The Witch and The Wardrobe.

“The Passion let them know that religion sells, and Tolkien’s Lord of the Rings [let them know] that fantasy sells,” Mitchell says. “So who brings the two together? Lewis.”

Yet whether Lewis sells will be beside the point for most evangelicals. The Oxford don with a mixed pedigree is not likely to go out of favor with a movement that stands for classic Christian faith and loves a good story.

Bob Smietana is features editor of The Covenant Companion.

Copyright © 2005 Christianity Today. Click for reprint information.

Related Elsewhere:

CT’s sister publication Christian History & Biographydevoted an issue to C.S. Lewis in 1985. It’s Winter 2005 issue, available Nov. 30, also covers Lewis, and is available for purchase from our site.

Christian History & Biography also featured Lewis in its top ten Christians issue: Apologetics: C.S. Lewis | The atheist scholar who became an Anglican, an apologist, and a patron saint of Christians everywhere.

In 1998 J.I. Packer, another former Oxford student, also discussed why Lewis became an evangelical celebrity.

Still Surprised by Lewis | Why this nonevangelical Oxford don has become our patron saint. (Sept. 7, 1998)

Previous CT articles on “Jack” include:

C.S. Lewis, the Sneaky Pagan | The author of A Field Guide to Narnia says Lewis wove pre-Christian ideas into a story for a post-Christian culture. (June 28, 2004)

J. R. R. Tolkien and C. S. Lewis, a Legendary Friendship | A new book reveals how these two famous friends conspired to bring myth and legend—and Truth—to modern readers. (Aug. 29, 2003)

The Dour Analyst and the Joyous Christian | In the realm of mental balance and personal peace, Sigmund Freud had nothing on C. S. Lewis. (April 19, 2002)

Two Cultural Giants | Both Sigmund Freud and C. S. Lewis were emotionally wounded as boys and struggled with depression as men. But a worldview can make a tremendous difference. (April 19, 2002)

Wisdom in a Time of War | What Oswald Chambers and C.S. Lewis teach us about living through the long battle with terrorism. (Jan. 4, 2002)

Forget ‘Normal’ | C.S. Lewis’s warning against panic during World War II resonates in our new crisis. (Oct. 19, 2001)

Mere Marketing? | Publisher, estate under fire for handling of C.S. Lewis’s identity. (August 6, 2001)

Aslan Is Still on the Move | There’s too little evidence to prove that anyone is ‘de-Christianizing’ C.S. Lewis. (August 6, 2001)

Myth Matters | C. S. Lewis bequeathed us a method and a language for sharing the gospel with the modern and postmodern world. (April 17, 2001)

Spring in Purgatory: Dante, Botticelli, C. S. Lewis, and a Lost Masterpiece | For slightly over five hundred years, the most famous and popular illustration of Dante’s Divine Comedy has remained effectively “lost.” (Feb. 7, 2000)

Walking Where Lewis Walked | My reluctant entry into the world of pilgrimage. (Feb. 7, 2000)

C.S. Lewis on Christmas | Lewis summed up Christmas in one sentence: “The Son of God became a man to enable men to become the sons of God.” (December 20, 1999)

Reflections | Clive Staples Lewis in his lifetime gave us many writings that explicate the Christian faith and walk. (Nov. 16, 1998)

Jack Is Back | The search for the historical Lewis. (Feb. 3, 1997)

If you’re really interested in Lewis, Into the Wardrobe should fill your every desire.

The Discovery Institute’s C.S. Lewis and Public Life site is another wonderful resource of papers about and by Lewis.

Still hungry for more? You’ll probably never have the time to read everything linked at the C.S. Lewis Mega-Links page.

The C.S. Lewis Foundation has even more on the man, as well as conferences, programs, and resources for Lewis aficionados.