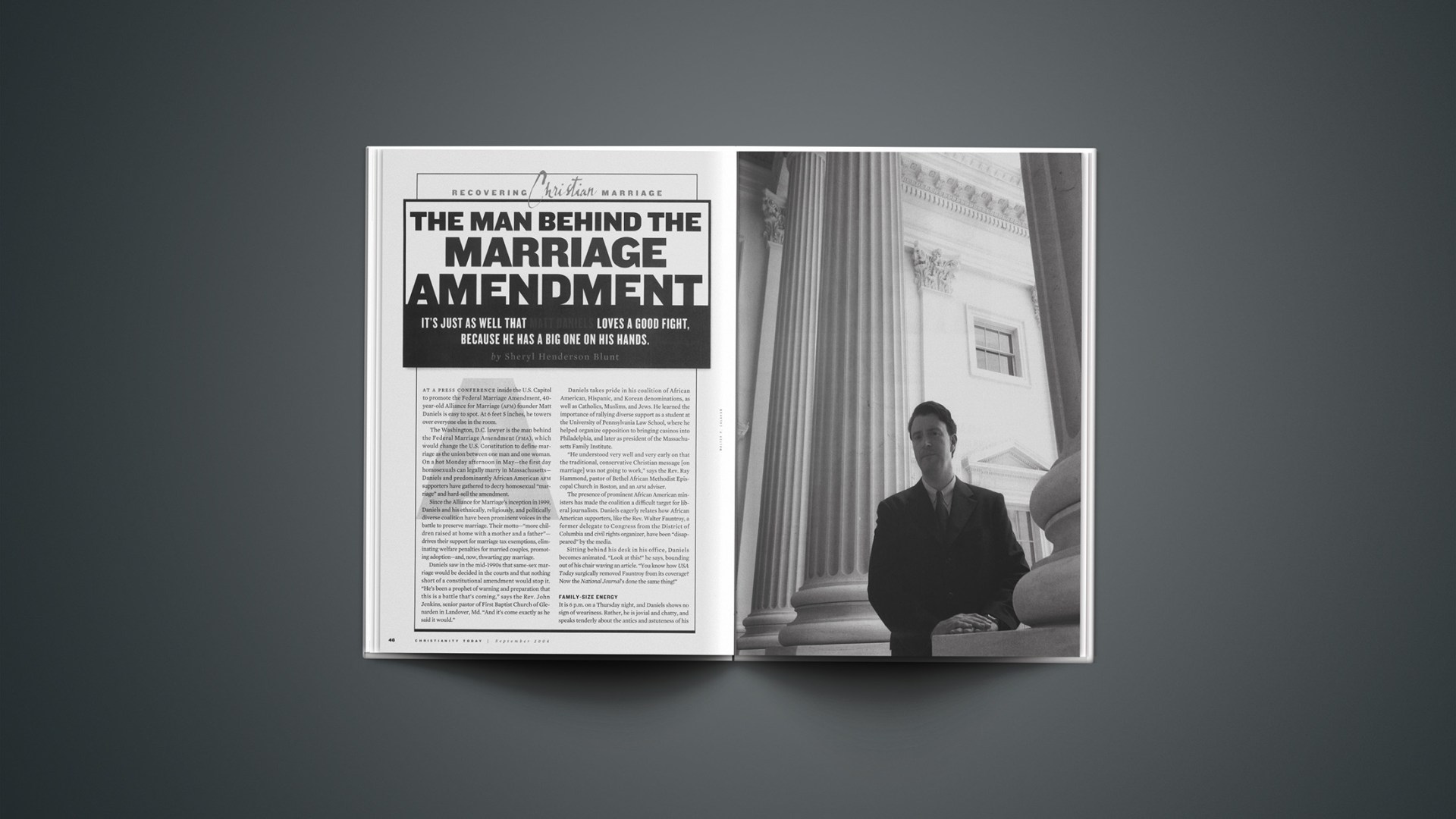

At a press conference inside the U.S. Capitol to promote the Federal Marriage Amendment, 40-year-old Alliance for Marriage (AFM) founder Matt Daniels is easy to spot. At 6 feet 5 inches, he towers over everyone else in the room.

The Washington, D.C. lawyer is the man behind the Federal Marriage Amendment (FMA), which would change the U.S. Constitution to define marriage as the union between one man and one woman. On a hot Monday afternoon in May-the first day homosexuals can legally marry in Massachusetts-Daniels and predominantly African American AFM supporters have gathered to decry homosexual “marriage” and hard-sell the amendment.

Since the Alliance for Marriage’s inception in 1999, Daniels and his ethnically, religiously, and politically diverse coalition have been prominent voices in the battle to preserve marriage. Their motto-“more children raised at home with a mother and a father”-

drives their support for marriage tax exemptions, eliminating welfare penalties for married couples, promoting adoption-and, now, thwarting gay marriage.

Daniels saw in the mid-1990s that same-sex marriage would be decided in the courts and that nothing short of a constitutional amendment would stop it. “He’s been a prophet of warning and preparation that this is a battle that’s coming,” says the Rev. John Jenkins, senior pastor of First Baptist Church of Glenarden in Landover, Md. “And it’s come exactly as he said it would.”

Daniels takes pride in his coalition of African American, Hispanic, and Korean denominations, as well as Catholics, Muslims, and Jews. He learned the importance of rallying diverse support as a student at the University of Pennsylvania Law School, where he helped organize opposition to bringing casinos into Philadelphia, and later as president of the Massachusetts Family Institute.

“He understood very well and very early on that the traditional, conservative Christian message [on marriage] was not going to work,” says the Rev. Ray Hammond, pastor of Bethel African Methodist Episcopal Church in Boston, and an afm adviser.

The presence of prominent African American ministers has made the coalition a difficult target for liberal journalists. Daniels eagerly relates how African American supporters, like the Rev. Walter Fauntroy, a former delegate to Congress from the District of Columbia and civil rights organizer, have been “disappeared” by the media.

Sitting behind his desk in his office, Daniels becomes animated. “Look at this!” he says, bounding out of his chair waving an article. “You know how USA Today surgically removed Fauntroy from its coverage? Now the National Journal‘s done the same thing!”

Family-size Energy

It is 6 p.m. on a Thursday night, and Daniels shows no sign of weariness. Rather, he is jovial and chatty, and speaks tenderly about the antics and astuteness of his two young children.

The Daniels family knows diversity. His wife, a family practice physician, is Korean American, and his closest relative, a half brother, is half black. Recounting his experiences with the AFM, Daniels suddenly launches into a comical impersonation of a high-profile religious figure he once met. It is this bounding enthusiasm, friends say, that is so appealing.

“When I met him, my first impression was that he’s very energetic and a great communicator,” says the Rev. Thann Young, pastor of Agape African Methodist Episcopal Church in Olney, Md., and one of the AFM’s advisers.

A protective father and husband, Daniels will not permit reporters to interview any immediate or extended family members. Numerous death threats directed at him and family members have made him cautious of exposing them to publicity, he says.

The AFM’s office location is a secret, and its entrance in a nondescript office park is unmarked. Daniels says the death threats started in 2001, when the AFM announced plans to introduce the amendment in the House. He has since come to expect them with each political success.

“The movement trying to destroy marriage is a very hateful, angry movement,” Daniels says. “The anger and hatred from many of the activists is quite intense.”

Daniels’s passion for preserving the traditional family stems from the conviction-solidified during law school and doctoral studies in politics at Brandeis University-that the courts are dismantling America’s democratic processes. “For him it’s very much a sense of calling … that this is what he has been equipped and called to do,” Hammond says.

His calling to defend the traditional family also comes from an urgent sense of responsibility toward his children and future generations. “If we fail to protect the legal status of marriage, our children will inherit a wasteland,” Daniels says. The erosion of traditional marriage “will change our social and cultural DNA.”

Violence and abandonment marked Daniels’s own unhappy childhood. He grew up in New York City’s Spanish Harlem, the son of a nominally Catholic mother and a father “intellectually hostile” to the gospel.

Daniels was two when his father, a writer and Russian-speaking translator, abandoned the family. It was the second of four marriages he would desert, leaving “a trail of human suffering in his wake.” Daniels recalls the uncertainty and fears of the resultant poverty.

“There was the constant sense that something terrible could happen to us at any moment,” he says.

One night Daniels’s mother got off at the wrong bus stop on her way home from work. Four men attacked her. Badly beaten and permanently disabled from a broken back, she turned to alcohol. She ended up on welfare.

Such experiences toughened Daniels; little seems to faze him now. He shrugs off criticism-which pours in from both liberals and conservatives-and relishes taking on critics.

He enjoys recounting stories of hostile press interviews and goes into such encounters believing he has more to gain than lose. “You know why I do these interviews even when I know they will do an ambush?” he asks. “It’s because the public is so deeply with us that any coverage increases our support.”

Young says that Daniels seems to thrive amid conflict: “He’s a very strong person.” He notes that Daniels regularly disarms angry reporters from gay-rights publications or advocacy groups. “He dumbfounds them,” he says. “He’s quick on his feet.”

Once after a hostile press conference, Fauntroy received a torrent of angry threats after gay-rights activists made public his home phone number. “Matt came to his defense like a tiger,” Young says. “He got on the phone with the group and said what an affront it was, that they were supposed to be about justice and human rights. He took them on.”

Conservative Pummeling

Yet Daniels is no darling of the Right either. Some conservative groups, including Concerned Women for America (CWA) and the Home School Legal Defense Association (HSLDA), criticized the Federal Marriage Amendment because it does not prevent state legislatures from approving same-sex civil unions and marriage benefits.

“The issue is, what is the legal recognition we give to people?” HSLDA chairman and general counsel Michael Farris says. “If [homosexual couples] can get 100 percent of the benefits of marriage, that’s marriage. And if Matt Daniels is willing to give them that, he’s disillusioning people and destroying the pro-family movement permanently.”

Many conservatives also complain that the afm avoids debate over the morality of homosexuality. Instead it relies on sociological and economic arguments.

“He has discouraged any honest discussion of homosexuality, which is what this debate should be about and is what the homosexual activists want to avoid at all costs,” says Robert Knight, president of the CWA-affiliated Culture and Family Institute. “Some people think it’s more pragmatic to throw away the moral card and the behavioral card and try to defeat homosexual activists by only touting the benefits of marriage. That is a losing strategy.”

Daniels replies that conservatives “position and posture to their subscriber base. It’s pleasing to those who read their newsletters, but if you want to win, you have to be realistic.” So he studiously avoids the moral dimension. He laughs when recounting a story of a national newspaper reporter who started off an interview by demanding to know his view of same-sex marriage. When Daniels insisted that the reporter answer the same question, he backed down.

He is a pragmatist who says he has learned from the failure of the Human Life Amendment: In striving for the perfect, one risks getting nothing. “If we had gone with our critics on the right, our effort would have suffered the same fate,” he says. “We had to fend off competing amendments.”

As a case in point, a group of conservative organizations known as the Arlington Group voted 25-2 against the FMA because they opposed the amendment’s “permissive” wording on civil unions.

As one Arlington Group member put it, “Basically Daniels said, ‘Look, I’ve done it. Either help or get out of the way.'”

Due largely to Daniels’s aggresive lobbying, most of the Arlington Group now stands with him. But, ironically, Senate opponents (liberal and conservative) tried to drop the FMA’s allowance for same-sex civil unions, rendering it more likely to fail.

Gospel Roots

Daniels is a practicing Presbyterian, but his Christian faith took root in the African American church when he was in his early 20s. Following the death of his parents two years apart, he felt “spiritually empty,” so he began volunteering in a search to find meaning.

“After being hit with the reality of death, I decided I didn’t have a foundation for my life,” Daniels says. “I believed I could build a superstructure, but there would be nothing underneath it.”

His search drew him into New York City’s homeless shelters, where he met African American volunteers. Their love and compassion impressed him.

“They started sharing the gospel with me, [and] the reason I listened to them in spite of the intellectual hostility I carried was their credibility.” The more he was around them, Daniels says, the more his “heart kept warming to God and the gospel.”

Daniels began attending black churches, where he says he was “warmly embraced as the only white guy in the place.”

“It was a grueling process,” Daniels recalls. “My mind had to be uprooted, in a sense, and it was a soil that was utterly hostile to faith and to God in particular.”

When he left for law school, Daniels took his newfound faith and passion for homeless ministry with him.

“It was a watershed moment for me when I came to Christ,” Daniels says. “I could clearly envision … how empty it would be as a partner at some law firm without a foundation for my life. After I became a Christian, law school took on a different meaning.”

Near the Penn campus, Daniels found a Presbyterian church and became involved in its outreach to homeless men. He also met his future wife, a co-leader of the church youth group.

“She thought I was some nice guy from the Midwest,” Daniels says with a laugh. “She was disappointed to find out I was a New Yorker.”

Having never seen a lifelong marriage modeled, Daniels doubted his ability to commit to one. He sought counseling from married couples within the church. “It seemed undoable to me,” he says. “But my Christian faith was also telling me that I wasn’t just going into this with my own resources, so I didn’t have to be in fear.”

Daniels is alert to the dangers his hard-driving personality and passion pose to family life.

“He is a very intense and committed guy who quickly understood his own propensity to cross the line between being very committed and very driven,” says Hammond, adding that Daniels deliberately sought out people to hold him accountable. “He’s said, ‘It makes no sense to be out there advocating marriage and have my own marriage go down the tubes.'”

Pressing On

Daniels’s tenacity and dedication to the Federal Marriage Amendment have taken him to the White House and to the Vatican, where he has made formidable allies.

Along with some in the Republican Party leadership, he has tried to place the debate on center stage in the 2004 presidential and congressional elections.

While Senate supporters were unable to bring the FMA to a vote in July, Daniels insists it is only the beginning. Wrapping up his press conference, Daniels predicts that more state supreme court rulings allowing gay marriage will galvanize public support for the FMA.

“When these lawsuits start, we will have the political trigger pulled in this national referendum on marriage and family,” he says. “We have real momentum now, but the best is yet to come.”

Sheryl Henderson Blunt is senior news writer for Christianity Today.

Copyright © 2004 Christianity Today. Click for reprint information.

Related Elsewhere:

The Atlantic Monthly has a profile of Matt Daniels, available to subscribers; USA Today‘s profile is available for free.

The Alliance for Marriage has more information on its activities, the proposed marriage amendment, how to get involved, information on marriage, and press excerpts on the amendment.

Christianity Today‘s past coverage of the gay marriage debate includes:

A Crumbling Institution | How social revolutions cracked the pillars of marriage. (Aug. 24, 2004)

What God Hath Not Joined | Why marriage was designed for male and female. (Aug. 20, 2004)

The Next Sexual Revolution | By practicing what it preaches on marriage, the church could transform society. (Aug. 27, 2003)

My Two Dads? Not in Florida | U.S. Circuit Court upholds ban on gay adoption (March 11, 2004)

Speaking Out: Why Gay Marriage Would Be Harmful | Institutionalizing homosexual marriage would be bad for marriage, bad for children, and bad for society. (Feb. 19, 2004)

Let No Law Put Asunder | A constitutional amendment defending marriage is worth the effort. (Jan. 26, 2004)

Massachusetts Court Backs Gay Marriage | Christians say gay activists will overturn marriage laws (Dec. 10, 2003)

‘AMan and a Woman’ | Activists say the Federal Marriage Amendment will be the defining issue in the next election. (Nov. 24, 2003)

The Marriage Battle Begins | Profamily and gay activists agree: Texas decision sets significant precedent. (Aug. 11, 2003)

Canada Backs Gay Marriages | Conservatives say decision could put pressure on dissenting churches. (July 16, 2003)

Marriage in the Dock | Massachusetts case on gay marriage could set off chain reaction. (April 25, 2003)

Christian Conservatives Split on Federal Marriage Amendment | Law would protect marriage from courts, but legislatures could still extend marital benefits to same-sex unions. (July 20, 2002)

Defining Marriage | Conservatives advocate amendment to preserve traditional matrimony. (October 1, 2001)

No Balm in Denver | Episcopalians defer debate over same-sex blessings for another three years. (July 17, 2001)

Marriage Laws Embroil Legislatures | New Englanders push for domestic-partner benefits. (April 26, 2001)

Presbyterians Propose Ban on Same-Sex Ceremonies | Change to church constitution, which passes by only 17 votes, now goes to presbyteries. (July 5, 2001)

Sticking With the Status Quo | United Methodists reject gay marriage, ordination. (May 15, 2000)

Presbyterians Vote Down Ban on Same-Sex Unions | Opponents say vague wording led to defeat. (March 29, 2001)

States Consider Laws on Same-Sex Unions California to vote on ‘limit on marriage’ in March (Jan. 10, 1999)

Presbyterians Support Same-Sex Unions (Dec. 10, 1999)

Pastor Suspended in Test of Same-Sex Marriage Ban (Apr. 26, 1999)

Same-Sex Rites Cause Campus Stir (Aug. 11, 1997)

State Lawmakers Scramble to Ban Same-Sex Marriages (Feb. 3, 1997)

Clinton Signs Law Backing Heterosexual Marriage (Oct. 28, 1996)