A field of shattered dreams lies south of San Francisco along Highway 101 down to San Jose. Newly emptied office buildings in Silicon Valley are a visible sign that hard times have hit the multibillion-dollar technology industry. While the legendary founders of Silicon Valley are retired millionaires, some in the next generation of high-tech heroes are losing big time. Billions of dollars in stock-market equity have disappeared as investors have sold off stock in publicly traded firms. The tech-heavy Nasdaq market has lost over half its value in the last 18 months.

But even as the downward spiral of the high-tech industry persists, a potent spiritual transformation is unfolding. Is God at work through a new alliance of Christian executives in Silicon Valley? Their faith-centered approach to wealth and power is revealing that the "next new new thing" may be the timelessness of Jesus Christ.

As workaholic executives burn out, this growing network of faith-focused business leaders is determined to save Silicon Valley's soul. The executives' aim of bringing biblical values back into the marketplace has the potential to change the high-tech corporations that are changing the world of work.

These executives have turned to Os Guinness, the evangelical author, sociologist, and consultant, as a key resource. In an interview with Christianity Today, Guinness said Christian business leaders in Silicon Valley have an "extraordinary opportunity" to deploy their business enterprises in ways that embrace a Christian worldview. "Silicon Valley will have a longer lasting and more global impact than the 1960s," says Guinness, who has observed California's Bay Area for 30 years. For Guinness, the firms of Silicon Valley are at the forefront of a "second Industrial Revolution" in which information technology will transform how people live and work.

During a recent tour of Silicon Valley firms, Christianity Today spoke with several of the most prominent Christians there about their high-tech, high-finance world, and how faith influences their work.

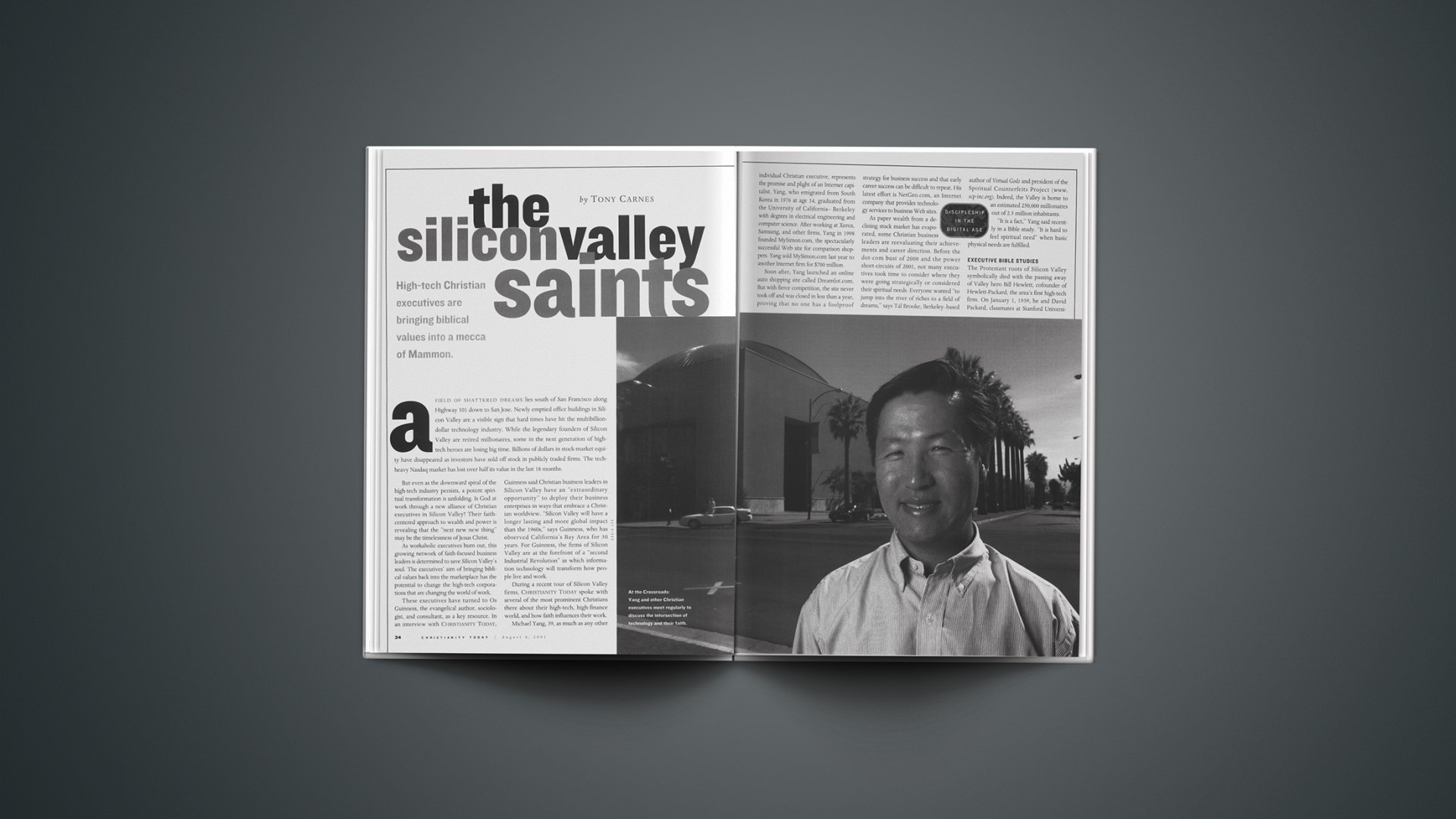

Michael Yang, 39, as much as any other individual Christian executive, represents the promise and plight of an Internet capitalist. Yang, who emigrated from South Korea in 1976 at age 14, graduated from the University of California- Berkeley with degrees in electrical engineering and computer science. After working at Xerox, Samsung, and other firms, Yang in 1998 founded MySimon.com, the spectacularly successful Web site for comparison shoppers. Yang sold MySimon.com last year to another Internet firm for $700 million.

Soon after, Yang launched an online auto shopping site called Dreamlot.com. But with fierce competition, the site never took off and was closed in less than a year, proving that no one has a foolproof strategy for business success and that early career success can be difficult to repeat. His latest effort is NetGeo.com, an Internet company that provides technology services to business Web sites.

As paper wealth from a declining stock market has evaporated, some Christian business leaders are reevaluating their achievements and career direction. Before the dot-com bust of 2000 and the power short-circuits of 2001, not many executives took time to consider where they were going strategically or considered their spiritual needs. Everyone wanted "to jump into the river of riches to a field of dreams," says Tal Brooke, Berkeley-based author of Virtual Gods and president of the Spiritual Counterfeits Project. Indeed, the Valley is home to an estimated 250,000 millionaires out of 2.5 million inhabitants.

"It is a fact," Yang said recently in a Bible study. "It is hard to feel spiritual need" when basic physical needs are fulfilled.

Executive Bible Studies

The Protestant roots of Silicon Valley symbolically died with the passing away of Valley hero Bill Hewlett, cofounder of Hewlett-Packard, the area's first high-tech firm. On January 1, 1939, he and David Packard, classmates at Stanford University, launched an electronic measuring-device company from a one-car garage in Palo Alto. Six decades later, Hewlett-Packard led the Valley in revenues, with $47.1 billion.

A close friend remembers that Hewlett, a longtime member of the liberal Palo Alto Presbyterian Church, had an old-fashioned devotion to God and country. Hewlett's son recalls how he would sit in his father's lap and learn "how to follow the score of Handel's Messiah." Out of his traditional Protestant ethic came the famous "HP Way" of teamwork, flat hierarchy, innovation, and quality.

In the last two decades, church attendance in the Valley has been hardly the norm. It was, in fact, a curiosity. Today, however, as executives count the empty workplace parking slots as layoffs persist, parking spots at evening Bible studies are in short supply.

"I could hardly get to sleep last night; I was so excited about what is spiritually happening here," says John Brandon, a top executive at Apple Computer, in an interview with CT. Start-up churches, new Bible studies, and a growing network of prayer groups are having a subtle but significant influence on the high-tech industry by changing the hearts and minds of entrepreneurs, who in turn are changing the way they work.

Silicon Valley Fellowship has emerged as a network of Christian high-tech leaders. It has organized itself into a parachurch ministry that sponsors small groups as well as monthly lunches. At a January event, for example, former Microsoft executive John Sage traced his career from Harvard to high-tech to founding Pura Vida Coffee, which markets high-quality coffee beans to support Christian ministry in Costa Rica.

At one of the new Silicon Valley Bible studies, Christian executives (many of whom asked not to be named) face their fears. During the session, the mood is glum. "I am sitting in the midst of company turmoil," David tells his fellow Silicon Valley executives.

"We are in a recession," another says.

"No, a depression," another CEO corrects.

Greg Slayton, the CEO of ClickAction.com, functions as the elder statesman of the Bible study. Slayton remembers that when he came to Silicon Valley, he sensed how even Christian leaders were under its spell.

"I couldn't get them to return my phone calls. I wasn't an immediate IPO [initial public offering of a stock] prospect," Slayton reminiscences with a touch of bitterness.

Now in his early 40s, Slayton's habit of walking light on his feet, as if he is ready to race at any moment, makes one want to run after him wherever he goes. But this evening, he too is on the edge of exhaustion from his frantic pace. "The sense of isolation is a curse," Slayton warns. "It is the curse of 10,000 acquaintances. You find no one to talk to when things go really bad."

During the meeting, one new member recounts his challenge. "I am winding down a company," he says. "There is such ugliness and not much charity." He was ill-prepared by his business school to make ethical decisions while in catastrophe. "I could have made a lot of money for the company and myself by ripping off our customers before we go out of business." As he speaks, his cheeks redden with anxiety and pain. He might have sold software that would have been orphaned one minute after his company died.

Many Christian executives in Silicon Valley keep something in their office to remind themselves of where they came from and to whom they are responsible. One executive's wall features three framed newspaper articles denouncing his ethics and leadership abilities.

"It keeps me humble," he says. Slayton has his kids' artwork spilling off the walls of his office into the hallway—looking more like the kids' finger-painting room than the office of the president. "It reminds me not to forget my family, and reminds my employees too."

As the discussion turns to how these executives may be Christian witnesses in the workplace, the Bible study has come to exactly where Slayton wants it: How to bring about lasting change. "What are we taking away to do differently tomorrow?" Slayton asks. "If there isn't some practical impact, we are wasting our time."

Praying for Intel

Immigrant-owned enterprises are now a majority of all start-up corporations in the Valley. A quick drive down Highway 101 to the south end of the Valley brings into view via Technologies, where an openly born-again executive, Chen Wen-chi, is turning his company away from its reputation as a cold-blooded attack dog in the chipmaking business to being both competitive and compassionate.

You would not guess, at first appearance, that Chen is head of the third-largest chipmaker in the world. He moves diffidently, even shyly, down the hall, in his rumpled black suit, white shirt, and dark tie. His calm and alert exterior signals his intelligence, discernment, and an ability to plan ahead. He quickly checks off the large and small changes he has made in the company to glorify Christ: strategic decision meetings preceded by prayer in every via facility worldwide, Bible studies and praise sessions at the end of the work week, and increased attention to needs in the local community.

"We don't just plop a factory down and forget the community now. We help with water treatment and give engineering scholarships," Chen says. "Even our chip names—Joshua, Samuel, Ezra—tell of our business struggles and how God has led us." Yet at first the feisty chipmaker put off invitations to attend church with replies like "You have got to be kidding! I tried it!"

Chen took a job at via Technologies in 1987, becoming CEO in 1993. Chen thought he couldn't fail, but he did. Under his leadership, the company foundered. Intel sued to put via out of business over patent infringements.

Suffering business pressure each weekday, he dismissed friends' invitations to church so he could catch up on his sleep. Whether he was in Taiwan, Hong Kong, China, or Silicon Valley, Chen's answer was always "No, I'm not interested."

But Chen couldn't sleep on any continent. He says he wasn't bothered by the state of business as much as by his feeling that the crisis showed he lacked some essential ingredient of life. He tried diets, fortunetelling, and more work. One of via's owners kept suggesting he go to church.

Finally, he says, "I thought I would give God a challenge. I asked, 'Lead me to believe you.'" His Christian friends joined in the prayer, though his older friends were more skeptical. "It was [God's] miracle that I changed. It took place by God continually placing challenges before me. Then in 1995 I decided the Bible is a logical book, and I became a Christian."

Chen announced his decision to his astonished employees. He and the chairwoman of his board started to pray that God would save the company and transform it to his glory. Chen knew that his life and his company were being changed fundamentally. He saw answers to prayer and old business partnerships renewed. His friends and acquaintances from earlier days do a double take when they see his big, dog-eared Bible flop on the table during business meetings.

"God is placing me in Silicon Valley so I can be his servant here," he says. "And it gives me more rewards. They now come from within. Before, I would fluctuate like the stock market." His view of business has changed, Chen says with a wry smile. "I even pray for the people at Intel now!"

Stepping Through God's Doors

Many other Christian executives are fighting for the survival of their firms, however, and some will lose. Katherine Leary, a New York transplant in Silicon Valley and the top executive with the distance-learning start-up Pensare, recently tried to merge her firm with another in a desperate attempt at financial viability.

Pensare started out with great buzz in 1997. There were the legendary founders like Dean Hovey, an entrepreneur sought by Steve Jobs for advice on designing the look for Apple Computer's Macintosh line. There were the education superstars like Harvard Business School, which adopted Pensare's system of delivering a high-quality graduate education and advice to corporate executives via the Internet. In January Mother Jones magazine featured Pensare as one of the two important shapers of a new high-tech style of long-distance learning. But inside the company there were round-the-clock meetings on how to survive.

"As a Christian, there is a huge opportunity when you are running a company to help find a road map through the confusion that goes on when you are going under, having a takeover, or layoffs, We have burned $37 million in four years and only have $1.5 million revenue to show for it," Leary says.

In spring 2000, the company was diving hard after three years of happy chaos. The CEO was a great Foosball (table soccer) player, and one cofounder claimed to be the best Foosball player in the Valley. While executives huddled in the back game room, creditors pounded at the front door.

Leary had resolved to quit, even though she originally had believed Pensare was a closed door that God had opened. Leary had played it safe in New York's corporate world for years, but she had a sense that she was more afraid of change than standing for Christ. Eventually she embraced change, taking a position at Pensare. After three difficult years, she went to the CEO and resigned.

"You can't resign because I am quitting first," he told a stunned Leary. She stumbled home in a daze. "I prayed, 'God, I thought we were really clear on this!'" The same day she intended to resign, Leary took over the CEO's job. "I believe that God put me in these circumstances for one reason or another. He cares as much about the job I do here as what I do in church."

But in March, the curtain on Pensare came down quickly. Leary was having lunch when she took a call from a Philadelphia executive, whose firm decided not to buy out Pensare. Within days, the first of 80 Pensare workers were laid off without severance pay. Within weeks, Pensare filed for bankruptcy and an auctioneer sold off its physical assets and products.

In late June, Leary, told CT, "We tried to be as noble as we could in shutting down Pensare." Workers gave her and another executive a standing ovation minutes after the layoffs were announced.

Leary said she has struggled with guilt since the firm closed, trying to determine what she could have done differently. "If there is a little personal hell, that is what it is. You go over every single move you made."

Leary told CT that her pastor pointed out to her that Peter didn't walk on water until he got "out of the boat." For Leary, getting out of the boat means leaving the corporate world for a job at Menlo Park Presbyterian. Leary will focus on the field of business leadership. "There is little relevant stuff about how to work, how to balance, break new ground."

Jumping off a Cliff

In Silicon Valley, financial risk-taking is a premier sport. Milo Medin, head of technology at ExciteAtHome, a leading broadband Internet service provider, once said the company could succeed only by investors' throwing themselves off a cliff. He had few volunteers.

But Medin's coworkers at ExciteAtHome understand: an emblem of the firm's whimsical, risk-taking culture is a slide that allows workers to move between floors at their headquarters.

"Two years ago, our network put on a lot of users," Medin told CT in an interview. "We needed a new backbone structure unlike anything anyone had built before."

He needed investors badly, and he told venture capitalists that they needed to bet the company on his new high-speed Internet structure. Even for ExciteAtHome, the risk was unnerving. "It was not a conservative bet," Medin says.

Much of Medin's credibility comes from his success in advocating TCP/IP (a computer protocol for the Internet) while he worked at NASA's Ames Research Center. "He's evangelical in his approach," recalls Christine Falsetti, project manager for NASA's research and education network. "Milo marshaled the fight to make TCP/IP the de facto standard."

ExciteAtHome is a joint venture of two companies: Excite—which hosts the world's fourth-largest Internet portal after AOL, Yahoo, and MSN—and At Home, a broadband Internet service. At Home's broadband system is Medin's brainchild. The reason he's about to bet the company on his plan is because of his faith in Christ. "Christians can be more aggressive risk-takers in the Valley," Medin says. "Our values are not wrapped up in business and career."

Before getting the go ahead, he asked himself, "What if nobody will do it the way we want?" He checked his engineering and he checked himself. "My answer was that God has put me here and led me along this path, so it will work out how he wants."

ExciteAtHome has taken Medin's bet, and Medin's souped-up network may rescue the company from other woes. As a Bank of America analyst puts it, Medin's network is a hidden jewel that will become the crown jewel. If it does, the execution of the business will fall largely on the shoulders of fellow Christian Byron Smith, the head of the consumer broadband unit.

Having managed consumer brands like Downy fabric softener and Mr. Clean for Procter & Gamble, and created the One Rate plan for AT&T, Smith came to ExciteAtHome a year ago to help the company market Medin's system.

Smith and Medin faced some hard questions when they proposed restrictions against pornography and adult chat rooms (called "clubs" at Excite). "The people here are incredibly libertarian, but at the same time, they are very ethical about their work, and to the stockholders." Smith and Medin were able to join forces to rein in the smut on the Excite Web site. They had to convince libertarian-minded executives that some boundaries are good. "I tried to draw some lines," Smith recalls. He appealed to the libertarian ethic and the good of the company. "There is some frankly illegal stuff going on, but it is very hard to control," he says. Smith also argued that the pornographic chat rooms were growing so fast that it was costing the company too much to carry them. "The bad stuff takes over."

Playing the Lord's Way

Guinness says that Silicon Valley Christians may draw inspiration from William Wilberforce's Clapham Circle, a group of 18th-century Christian friends and industrialists who focused attention on England's social ills and on developing moral leadership. "Wilberforce was on the board of 69 different initiatives at one time, from founding the first Bible society to abolishing slavery to establishing the national art gallery," says Guinness.

Yang, for his part, is a key supporter of a new Christian university in Korea. Slayton, who worships at a poor and predominantly African-American church in Palo Alto, champions Christian microenterprise development in poor countries. Nonetheless, spiritual renewal in Silicon Valley is just beginning. It will take decades to determine if, in fact, the renewal will have a lasting influence.

In the meantime, Slayton says the future of Silicon Valley hangs in the balance, and Christian business leaders play a critical role in being a moral counterweight to the pursuit of wealth and success.

Thousands of private planes take off and land at the airport just around the corner from Slayton's office in Palo Alto. Across the street sits the stately Ming's Chinese Restaurant, the regular site of multimillion- and multibillion-dollar deals. Slayton's own company hasn't done too badly either, seeing a 1,300 percent increase in revenue from third quarter 1999 to third quarter 2000. The Jaguars and Benzes flow along the street onto the entrance ramp of Highway 101 in front of Slayton's office.

"It is never quite enough," Slayton says. He knows. At one point he was so busy running a previous company that he forgot his wife's birthday and his promises to be together on their wedding anniversary. He learned that he needed to play the game in the Lord's way. "I have told Marina a hundred times since then that she was right. Now I rarely work on Sunday."

Slayton encourages all his employees to do the same, and to go home no later than 7:30 each evening. Slayton and his fellow Christians, Chen, Leary, and Medin, are redefining community, business, success, and risk.

"If you are willing to bet your job on your beliefs, you can go a long way," says Medin's oft-repeated war cry. Christians in high tech realize that the second act of the Internet revolution may see its power brokers trade their shattered dreams for God's grace and truth.

Tony Carnes is CT's senior news writer and the editor, with Anna Karpathakis, of New York Glory: Religions in the City (New York University Press).

Copyright © 2001 Christianity Today. Click for reprint information.

Related Elsewhere

A ready-to-download Bible Study on this article is available at ChristianBibleStudies.com. These unique Bible studies use articles from current issues of Christianity Today to prompt thought-provoking discussions in adult Sunday school classes or small groups.

Related articles appearing on our site today include A Church for Internet Entrepreneurs and Reporting with the Top Down.

Silicon Valley Fellowship is a community of Bay Area business professionals that equips and encourages its members in their pursuit of Christ-like living and a transformed Silicon Valley.

When Electronic Business recently profiled Wen-Chi Chen, he came to the interview Bible in hand.

Companies discussed in the article include: mySimon.com, NetGeo.com, Hewlett-Packard, Apple Computer, ClickAction.com, and Excite@Home.

"The Silicon Valley" name is derived from the dense concentration of electronics and computer companies there since the mid-20th century.

A December 2000 study found more Internet users log on for religious purposes than for many secular reasons.

Tal Brooke's Spirtual Counterfeits Project is online. His book Virtual Gods is available at Amazon.com and other book retailers.

Read January's Mother Jones article on Pensare and long-distance learning.

Pura Vida Coffee's Web site offers five kinds of coffee and more information on where their money goes.

Previous Christianity Today coverage of Pura Vida includes:

Coffee That Cares | A Costa Rican church underwrites an urban outreach effort with premium coffee sales." (Oct. 5, 1998)