No, this is not a classful of prodigies. Gordon begins by going over the results of a test on the Genesis account of the Fall and the myth of Pandora’s Box. She is not pleased with her students’ performance.

“Why did Eve eat the apple? It was not because the apple was pretty, as one of you wrote.”

Gordon cajoles the students, teases them, and occasionally commends them, calling on them frequently by name (always prefaced by “Mr.” or “Miss”). Clearly they love her.

The class proceeds to Aristotle. They are working on his famous account of the nature of tragedy, and this session is devoted to reviewing the key terms, with a good deal of reading aloud and reciting definitions.

At this level, Gordon explains after class, the goal is to teach the students the basic vocabulary and analytic tools they will need to understand tragic drama. By the time they are seniors in high school, they will be able to employ these tools with great ease.

For the 7th-graders, she keeps the lesson simple, concrete, and fast-moving. The fall of a “man of noble birth”? Yes, President Clinton, guilty of hubris (and never mind that his birth was rather humble; he attained a high estate): “He thought he was above the moral law.” But then another example: “When he arranged the Watergate break-in, President Nixon thought he was above the law, too. That’s hubris.”

Established in 1995, Logos is one of thousands of schools, large and small, founded by evangelical Christians in the past 30 years. In 1960, when traditional Catholic parish schools were still going strong, evangelicals overwhelmingly sent their children to public schools. Today, a generation later, although a majority of evangelical children are still educated in public schools, a significant minority is attending Christian schools or is schooled at home.

In part this change came in response to the ongoing crisis in public education, the dimensions of which have been widely reported. Twenty-five years ago there was a fierce debate about the state of America’s schools, spurred by reports of falling scores on the Scholastic Aptitude Test (SAT). Critics traced the decline to changes made in the 1960s under the banner of “progressive” education. Defenders of the schools said that the fuss over test scores obscured the big picture: in fact, they said, public schools were better than ever!

Today it is much harder to find anyone taking that rosy view. President George W. Bush has said that education reform will be the top priority of his administration. Measures of student performance in the basic skills of reading, writing, and mathematics continue to be bleak. In Chicago’s schools, despite more than ten years of expensive and highly publicized reforms, just over a third of the students read at grade level. Violence in the schools is on the increase; in New York City schools, reports Robert Kolker in New York magazine, sex attacks have tripled in the last decade. Nor are such woes limited to big-city districts; consider the wave of shootings in schools large and small, suburban and rural.

On top of these concerns, there is an acute shortage of teachers. “Who Will Teach Our Kids?” asks a Newsweek cover story, adding that “Half of All Teachers Will Retire by 2010.” Right now, today, schools across the country are desperate to recruit qualified teachers—or at least a few live bodies.

But the explosive growth in Christian schools and home schooling can’t be attributed solely to the crisis in public education. Shocked by the drift of the culture, many Christian parents no longer see themselves as comfortably at home in a generically “Christian” America. They are convinced that their children need an explicitly biblical framework for their education, a countercultural grounding that will prepare them for life in a resolutely secular society. Indeed, many proponents of Christian education argue that there isn’t any other choice for parents who genuinely care about the formation of their children both intellectually and spiritually.

On the other side stand Christians who believe that now more than ever the public schools need the active support and participation of committed believers. Unlike private schools, public schools can’t pick and choose their students. They must take all students—including, under the terms of the Americans With Disabilities Act, those whose handicaps require enormously disproportionate resources of time and attention and money. Nor can the public schools count on strong parental involvement and a set of core values shared by families, teachers, and administrators. To abandon the public schools, these advocates of public education argue, is to forsake our Christian responsibilities to the society in which we live, particularly our responsibilities to its neediest members.

Both sides in this debate are passionate; both can draw persuasively on Scripture and Christian tradition. And the way they frame the issue leaves little room for common ground. In practice, though—in everyday reality—the battle lines are not so neatly drawn. Many staunch advocates of public education turn out to be sending their own children to private schools. Many Christian parents are quite happy to send their children to public schools when they live in cities and neighborhoods where the schools are excellent. Many public school teachers are committed Christians. Perhaps that’s one reason for the resounding defeat of voucher proposals in state after state last November.

To put this often rancorous disagreement in perspective, and to get a closer look at the state of American schools at the beginning of a new century, Christianity Today visited two schools in Dallas: Logos Academy, “a private, Christ-centered, classical college preparatory school for students in the seventh through twelfth grades,” and L.G. Pinkston High School, a public school in a largely African-American section of town.

A West Side Story

West Dallas is a template of inner-city America in 2001. There is the obligatory sprinkling of boarded-up shopping centers and overcrowded public-housing tenements, and the familiar sight of currency-exchange shops and liquor stores with windows shrouded in metal bars. If a filmmaker needed a backdrop of standard-issue urban blight, this would be the place to shoot.But, as in many urban areas today, there are also signs of resurgence: a new supermarket and KFC restaurant have risen up in what used to be a vacated strip mall; affordable single-family homes occupy land that once held rows of housing projects; the Pinnacle Park industrial development, with a handful of bustling companies, now stands where once there was only a weed-infested field.

And then there’s L.G. Pinkston High School. The dingy white hallways and dated classrooms don’t suggest a cutting-edge educational facility. And, to be frank, Pinkston High is about as cutting edge as a butter knife. To those who have been around awhile, the school building does not look that much different from when it opened its doors in 1964—except that then it was fresh, and now it’s old. The metal detectors at the entrance are a new feature. Still, there is optimism stirring within Pinkston’s walls.

Four years ago, Texas’s Academic Excellence Indicator System (AEIS) listed Pinkston as a low-performing school. Reading levels were down. Dropout rates were up. And scores were below average on the all-important Texas Assessment of Academic Skills (TAAS), which President Bush has held up as a model for making schools accountable. Since then, Pinkston has lifted itself to an acceptable AEIS rating. The school is graduating more students, and has seen steady gains in reading and math scores. There’s still a sizable distance to climb before Pinkston can claim a spot among Dallas’s elite public schools, and some would dismiss such ambition as idealistic whimsy. But Pinkston’s current optimism stems from a willingness to indulge such dreams.

One of the forces behind this hope is the school’s new principal, J. Leonard Wright. A tall man who commands attention simply by walking into a room, Wright looks like he’d be just as commanding behind a preacher’s pulpit or on a judge’s bench. Before the first bell at 8 a.m., he’s on the job: meeting with teachers and staff, monitoring the premises, encouraging straggling students to head to class. Throughout the day, outside his office there is a steady buzz of people needing his attention. In between there is paperwork to be completed, phone calls to take, and more hall-monitoring during the lunch periods. Wright typically gets around to eating his own lunch at 3 p.m. School dismisses at 3:45.

“It’s a demanding job,” he says, “but I love what I do. I’m passionate about education. I’m passionate about teaching young people.”

Wright, 46, started his career as a high-school teacher in 1977. In the 1980s he did a stint as a petroleum technologist for an oil company, but after five years the lure of the classroom was too much. He returned to education and quickly worked his way into administrative duties. He came to Pinkston last year after several years as principal of a middle school in Wichita Falls, 125 miles northwest of Dallas. Today, in addition to his work at Pinkston, he is completing his Ph.D. in educational leadership. He likens the job of running a school to that of managing a large business. “There’s a certain amount of customer service that goes along with this,” he says. “We’re teaching young people, but we’re also listening to them, trying to discover who they are and what they need. When I talk to students, there’s a lot of counseling that happens. We’re helping them develop a compass for their lives.”

For many Americans, the prevailing image of an inner-city high-school principal is that of “Crazy” Joe Clark, the real-life New Jersey principal portrayed by Morgan Freeman in the 1989 film Lean on Me. This archetype of the urban school administrator is one who spends the bulk of his time keeping order. He carries a big stick (in Clark’s case, a baseball bat), and will not hesitate to circumvent “the rules” if it means getting through to a kid. He is stern but compassionate, controversial but effective. The most memorable scenes from Lean on Me saw the no-nonsense Clark confronting gangbangers and unruly students with vigilante courage. Without trying, Wright evokes the look of the fearless school chief and disciplinarian. But his work is decidedly less dramatic.

“As a rule, I don’t do discipline,” Wright says. “We have a philosophy here that the principal should not be involved in the day-to-day disciplining because we want the student to know that when he comes to see me, it’s really serious.”

In fact, Pinkston runs counter to many of the stereotypical notions about urban high schools. Pinkston records few instances of violence or student disruption. Gang activity has decreased significantly over the years, thanks in part to better partnerships between the school, parents, and churches.

To be sure, the majority of Pinkston’s 820 students come from nonwhite backgrounds; according to Wright, the school is 53 percent African American and 42 percent Hispanic. And, yes, the school has faced challenges in finding its academic legs—and the kind of funding that could help it update its equipment and facilities. (It doesn’t help that the number of students has declined significantly since the school opened.) Nevertheless, Pinkston continues to produce sharp graduates, many of whom go on to become doctors, lawyers, and teachers. Dwayne Moffitt Jr. will soon be one of those alumni.

Moffitt, who graduates this month, has maintained good grades throughout his four years at Pinkston. He was named this year’s “Mr. Pinkston,” the school’s top student ambassador. In the fall, he plans to attend Dallas Christian College to study theology and business. His long-term goal is to return to the West Dallas area as a minister and civic leader. “I want to give back to the community,” he says. “I’d eventually like to start the first black-owned bank in this neighborhood.”

Some might look at Moffitt as the shining exception to the rule. Earlier this year, The Dallas Morning News wrote about him in terms of what he hadn’t done: “He could have joined a gang. He could have dropped out of high school. He could be serving time in jail. Instead . …” Such sermonizing is understandable, given the statistics on being a black man in today’s society. Still, it minimizes Moffitt’s intelligence, hard work, and faith when he’s viewed as having escaped rather than achieved.

Moffitt and other top Pinkston students are used to these types of inverted perceptions. “There’s so much hidden talent here, but you might not recognize it because of the way our schools have been stereotyped,” Moffitt says. “Pinkston is a good school. It’s not what they have labeled it to be. They say that West Dallas will never go anywhere and never amount to anything and that the students who go to schools here will never succeed past the 12th grade, but that’s not true.”

Transforming Pinkston’s image is one of Wright’s top priorities as principal, and he plans to do it, in part, through boosting the school’s academic credibility (a feat that would also invite increased government funding). A school should be driven by instruction, he says, and Pinkston needs to adopt that mindset.

“We don’t have a single National Merit Scholar,” Wright says. “For a school our size, that’s not good. I would like to see some National Merit Scholars coming out of this building. I would like to see greater emphasis placed on our AP [advanced placement] program. Students making good scores in the ap program will make us competitive with other high schools. We have a lot of students who get scholarships, but I would like to see us go to that next level.”

Wright is also working to improve his school’s technological assets. New computers, with Internet access in every classroom, have been an ongoing promise to Pinkston’s teachers and students for years now, but the school district funds never seem to materialize. Wright, however, was able to get some of the computers this year.

Some blame Pinkston’s lack of funding on a long history of racial segregation in Dallas. In 1985, a group of West Dallas residents filed suit against the city and the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development, claiming that the city’s public-housing system (one of the largest low-rise housing developments in the nation) had been segregated and unequal for decades. A federal judge agreed and ruled that the system be reformed. Substantial improvements have been made during the past 10 years, but many critics still point to that case as evidence of systematic discrimination against the West Dallas community—and its schools.

For now, Wright feels Pinkston is doing wonders with the cards it has been dealt. The school has launched several vocational programs, including a state-certified school of cosmetology and advanced courses in auto mechanics and computer maintenance, as well as a special-education program as mandated by the Americans With Disabilities Act.

The new principal says he’d like to see all of his students embrace “a post-secondary orientation.” But, he adds, training students for skilled trades doesn’t undermine that vision. “The reality is that everyone is not going to go to college. So I think the other options we offer here are important.” It’s what he calls good “customer service.”

Countercultural Scholarship

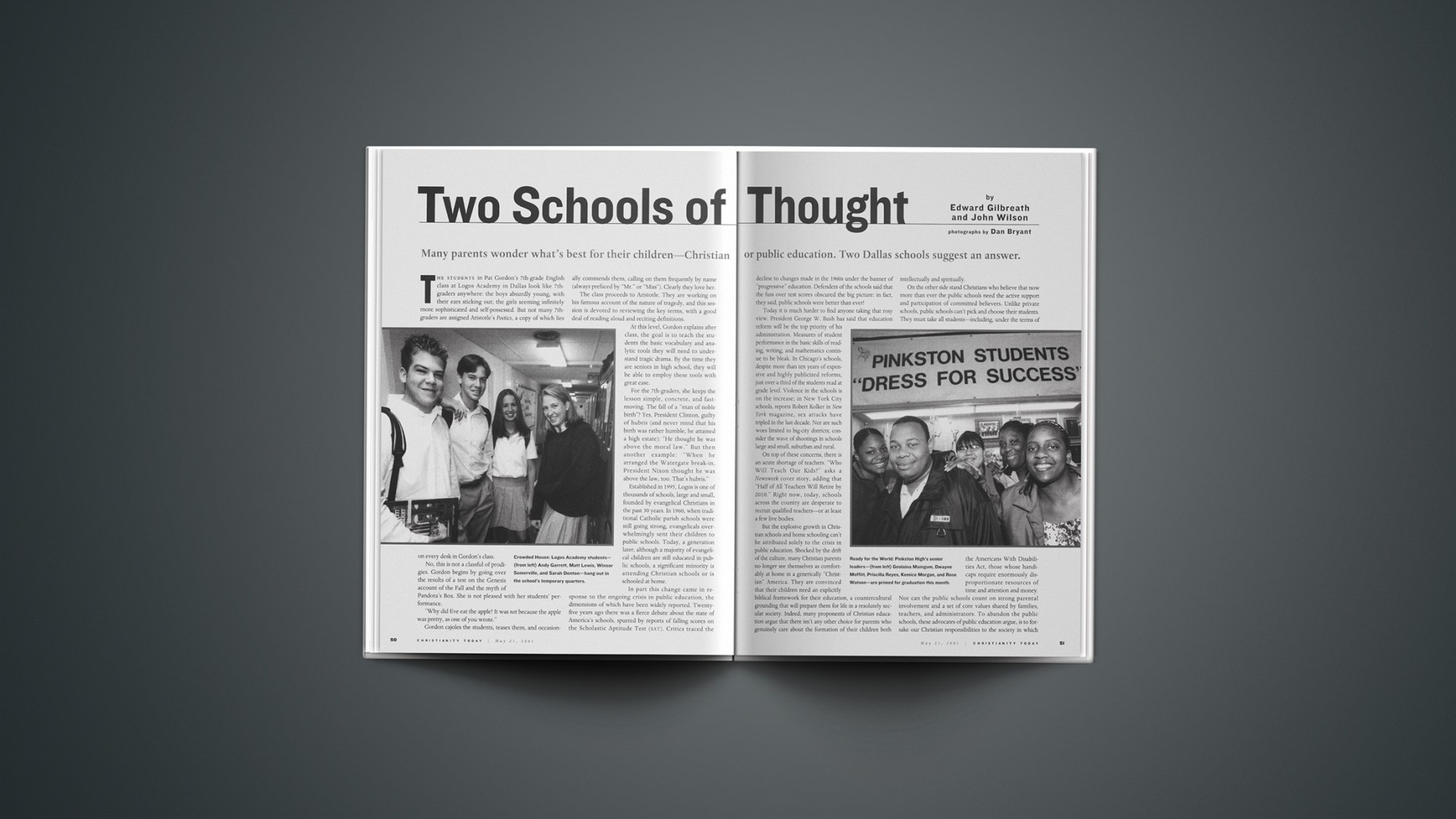

Across town from Pinkston, in a neighborhood of strip malls and modest suburban homes, Logos Academy is housed in temporary quarters on a church property, where classes meet in Sunday-school rooms. The students, arrayed in the official Logos uniforms of white shirts, blue sweaters, and khaki slacks or skirts, seem at home in the church’s cramped confines. Approximately 90 students are enrolled at Logos, which hopes to move to its new campus in northwest Dallas next year.Logos defines itself “first and foremost” as “a community of like-minded families. The school is a parent-involved institution. Faculty and staff serve parents.” Headmaster John Seel Jr. emphasizes the importance of a family interview for prospective students. He’s passionate about the need for parents to be deeply involved in their children’s education and indeed in every aspect of their lives, while at the same time instilling independence.

Only in the modern era, Seel observes, have students been so rigidly segregated from the adult world. “I don’t believe in adolescence,” he says. “We treat our students as young adults.” Demands are high, but students are given an unusual degree of responsibility as well. When considering a potential faculty member, Seel meets with the five student prefects, who will have had a chance to see the candidate in action. “I will never hire a faculty member unless the students give me the thumbs-up,” he says.

If the word earnest could be retrieved from mothballs—if it could be used without irony—that would be the word for Seel. With his owlish spectacles, suspenders, and blue blazer, his athlete’s build (football was his sport), and his unfeigned passion for moral education, he is the very model of a modern Christian headmaster.

Raised in Korea, where his parents were medical missionaries, Seel, 48, received an M.Div. from Covenant Theological Seminary and a Ph.D. in American Studies from the University of Maryland, College Park. An astute cultural commentator—he quotes from Rolling Stone and Wired as well as from Augustine and Calvin—he has written and edited several books, including most recently Parenting Without Perfection: Being a Kingdom Influence in a Toxic World.

In addition to Seel, Logos has attracted a number of highly qualified teachers. Most of the 14 or 15 faculty members have advanced degrees; five have doctorates. They are masters of their subject matter, and the school’s claim that every class is taught at the advanced placement level is no idle boast.

A cynic might wonder why someone so highly qualified would want to teach high-schoolers, let alone 7th-graders. Sometimes the cynic would be right. Faculty have come and gone, sometimes in midyear, sometimes with a push from the administration.

But others—like Jon Bailey, who has his Ph.D. in theological studies from the University of Notre Dame, and Preston Jones, a contributing editor for CT’s sister publication, Books & Culture, who has his Ph.D. in history from the University of Ottawa—have come to Logos because they find there an attractive alternative to an academic culture that has lost its moorings.

Jones has the intensity of his Welsh ancestors (fierce nonconformists, one suspects). He’s a young man of strong convictions, strongly expressed. He came to Logos last year from California State University, Sonoma, where most of the students he taught were en route to certification for classroom teaching. “The Cal State system is the biggest producer of public education in the U.S.,” Jones says, “and of the hundreds of students I taught, there was only one I would be happy to have teaching my own child.” Surely, we said, the students weren’t that bad. But Jones was adamant. These teachers-to-be, he said, had been abysmally educated themselves, and were qualified only to pass on the sort of inferior education they had received.

In contrast, he said, “it’s our aim at Logos to produce Christian students who are bright, keen, capable, and humble; students who will know American history better than the adjunct professors at their universities; students who can read Virgil and St. Paul in the original; students who are, in Neil Postman’s words, ‘crap detectors.'”

Jones acknowledges that maintaining an active intellectual life and staying current in his field (publishing articles in professional journals, for example) while teaching a full load at Logos has been more difficult than he imagined. “I don’t know how long I’ll be able to keep it up,” he says near the end of his first year. If Logos is serious about creating a learning community in which genuine scholarship plays a part, the school will have to free up some time for the faculty members who are scholars as well as teachers.

A commitment to scholarship at that level would be countercultural in the largely evangelical culture from which Logos draws its students. Much of the literature that Logos uses to sell itself emphasizes the contrast between public schooling (in caricature) and Christian schooling. That’s a pragmatic strategy: most Christian kids in Dallas go to public schools, Seel told us, so public education is the competition. But the real context of what Logos is trying to accomplish, he added, is what Mark Noll calls “the scandal of the evangelical mind.”

For too long, Seel believes, evangelicals have underestimated or even actively disdained the role of learning in the Christian life. The classically based Logos curriculum, which includes three years of Latin as a graduation requirement, stands in stark contrast not only to current trends in public education but also to much that passes under the name of Christian education.

Logos is countercultural outside the curriculum as well. The school offers a series of public evening lectures featuring outside speakers and Logos faculty. In January, for example, Logos students and parents heard prizewinning architect David Stocker speaking on “A History of Academic Architecture: The Importance of Context in the Life of the Mind.” Stocker challenged what he called the “architectural gnosticism” that prevails in the evangelical community, the implicit notion that “matter doesn’t matter.” Such learning outside the classroom doesn’t lead to a degree or some other measurable goal; it is a good in itself.

Of God and Choices

Matt Lewis, a junior at Logos Academy, spent his freshman and sophomore years at Highland Park High School, one of Dallas’s most wealthy and accomplished public schools. Lewis was an excellent student at Highland Park, but, he says, both he and his parents felt the school lacked a moral thrust. “I transferred to Logos because I wanted Christ to be at the center of my education,” he explains. Winsor Somerville, also a junior, was home-schooled before entering Logos. For her, a classical Christian education was a natural next step.Both Lewis and Somerville came to Logos because there was a sense that public education has abandoned Christian values and falls short in shaping the total person. Though their concerns may be valid, the influence of committed Christians in public schools is often underestimated.

Lunch hours at L.G. Pinkston, as at most high schools, are filled with boisterous teenagers discussing the weighty issues of adolescent life over plastic trays full of nondescript cafeteria food. But three days a week at Pinkston, in addition to the teachers and staff assigned to patrol the hallways, you’ll also find volunteers from West Dallas Community Church. On a recent Tuesday, church members James Boyd and Jeff Strong roamed the lunchroom, checking up on students who participate in their outreach programs at the church’s community development center.

At many public schools around the nation, Boyd and Strong’s presence on campus during school hours would come dangerously close to flouting church-state boundaries—might even provoke a lawsuit. At Pinkston, however, the subject is hardly an issue. For years, long before President Bush made “faith-based programs” front-page news, volunteers from the West Dallas congregation have mentored Pinkston students and tutored them in class work and for TAAS testing. According to Pinkston community liaison Hope Williams, any reputable group committed to serving the school is welcome. “Many ministries in the area have gone out of their way to assist our students,” Williams says. “West Dallas Community Church has, more or less, adopted the school.” Indeed, the church’s pastor, Arrvel Wilson, was a member of Pinkston’s first graduating class and serves as a community adviser to the school.

Boyd, who is the youth pastor at West Dallas Community Church, also has worked as a substitute teacher at Pinkston. He says most of the students are just happy to know someone is taking an interest in them. “We mainly talk to the kids about life,” he says. “Every student that I know wants to show me his or her report card. They see us as authority figures who care about what’s going on in their lives.”

Charles Fisher, Pinkston’s principal for 13 years before J. Leonard Wright’s arrival, had an open-door policy for religious groups. So far, Principal Wright, a Baptist who sometimes teaches Sunday school, is following suit.

The decor in Wright’s office is sparse. There are stacks of papers and spiral binders on his desk. The place looks lived in, but it’s clear that he hasn’t lived there long. On the shelves is an assortment of books, family photos, trophies—and a Bible. It’s evident that he takes his beliefs seriously. Still, he understands and respects the established lines of separation. “A generation ago, the consistency of religious tradition among all people could be assumed,” Wright says. “That has changed. Now it’s much more pluralistic.”

Wright’s allegiance to public education comes through loud and clear when he addresses the hotly debated issue of providing school vouchers for families who want to remove their children from inferior public schools. “I’m not in favor of taking money away from the public schools,” he says. “How are you going to aid and assist public schools by taking their funding and putting it somewhere else?”

Wright adds, however, that he’s in favor of reforming or shutting down any school that continues to be ineffective after it has been given a fair shot to succeed.

Some of Pinkston’s leading students would welcome a voucher program if it could help them attend a better school. But that’s doubtful, they say. “Yes, I’d take vouchers to go to a private school in a minute,” says Rose Watson, senior class vice president. “But from what I’ve read about them, it would not be realistic to think that they would provide enough money to pay for a private-school education.”

More families are choosing where they want their children to go to school, whether it be to private religious schools or charter and magnet schools in the public system. President Bush’s education proposals seek to extend those options. Wright and Watson remind us, however, that in the effort to “leave no child behind,” real-world economics often conspire against good intentions.

Parallel Paths

The closer you look at real schools—schools like Logos and Pinkston—the more absurd it seems to argue that Christians must throw their weight either with public education or with private Christian education. Both Logos and Pinkston are founded on a vision of community. The Logos community is intentional, exclusive, and self-defined. It entails a shared commitment to Christian values. The Pinkston community is shaped by proximity, inclusive, defined by state and local governments. It entails a shared commitment to American democratic values. There are Christian warrants for both visions.At Logos, in a meeting with the school’s five prefects, there is spirited talk about future plans. The students agree that Logos has prepared them for life beyond a Christian school. None express anxiety about living out their faith in less insular environs. At least two seniors, Elizabeth Baxter and John Campbell, reveal that they have applied to secular colleges.

In a way, their journey mirrors that of Pinkston students like Dwayne Moffitt, who is leaving a public high school to attend a Christian college. All are excellent students. All are passionate Christians. And all want to use their education to make a difference.

Edward Gilbreath is associate editor of CT and John Wilson is editor of Books & Culture.

Copyright © 2001 Christianity Today. Click for reprint information.

Related Elsewhere

More Christianity Today articles on public and private schools are available in our education area.Further ReadingDiane Ravitch’s Left Back: A Century of Failed School Reforms (Simon & Schuster, 2000) puts the current crisis in American public education in historical perspective, showing how schools have been used to promote shifting social agendas. Her modest conclusion: “To be effective, schools must concentrate on their fundamental mission of teaching and learning. And they must do it for all children.” In Tinkering Toward Utopia: A Century of Public School Reform (Harvard University Press, 1995), David Tyack and Larry Cuban cover some of the same territory; they too offer a modest realism in contrast to the extravagant claims of many educational reformers, with a focus on helping teachers become more effective.The leading figure in the classical Christian education movement is Douglas Wilson, whose Logos School, founded in Moscow, Idaho, in 1980, is the prototype. Wilson’s book, Recovering the Lost Tools of Learning: An Approach to Distinctively Christian Education (Crossway, 1991), is the best introduction to the ethos of the movement.

Yahoo’s has links to news articles and opinion pieces in its full coverage areas on Education Curriculum and Policy and School Choice and Tuition Vouchers.

Public Agenda‘s education area is one of the best sites for nonpartisan statistics, demographics, and opinion-poll results. It also has several articles outlining education reform issues, who has taken what sides, and what’s at stake.

The U.S. Department of Education site has statistics, “the nation’s report card,” and other resources.

Some “local” resources are excellent for readers around the country. The Texas Education Agency site is a handy reference for information about the public education in Logos Academy’s and Pinkston High’s state. The Washington Post‘s education section archives all of the paper’s related news articles, columns, and other pieces. Chicago public radio station WBEZ’s “Chicago Matters” series on education, “Education Matters,” runs through the end of this month. All of the audio segments, of which there are dozens, are available online.

SchoolReformers.com has links to news stories and other resources favoring charter schools, vouchers, tuition tax credits, and other such “market-based school reforms.” The Center for Education Reform, meanwhile, is one of the leading organizations pushing for such reforms.

Douglas Wilson’s Association of Classical & Christian Schools seeks “:to promote, establish, and equip schools committed to a classical approach to education in the light of a Christian world view grounded in the Old and New Testament Scriptures” through the Trivium (grammar, logic, and rhetoric).