Every year, a few dozen folks from Willow Creek Community Church make a pilgrimage to 121 Kellogg Place in Wheaton, Illinois—the home of Gilbert Bilezikian and his wife, Maria. The pilgrims pass a sun porch where Bilezikian, the theologian behind Willow Creek, spends most of his time in the summer and fall.

“We built that porch a few years ago, right where Bill Hybels drove his motorcycle the day he came to see me in 1975,” Bilezikian says of his former student, who would become the church’s senior pastor.

The Willow Creek pilgrims make their way to the backyard, past Maria’s elaborate flower garden and the tomato and cucumber plants her husband tends (“I am better known for my salads than for any theological work I’ve ever done,” he notes, only half in jest), to the spot where Willow Creek was born.

“Right here,” says Bilezikian, standing in the middle of his lawn. There Hybels, then no more famous than any other recent college grad, roared up on his bike and said, “Dr. B., you and I are going to start a church.”

Building community

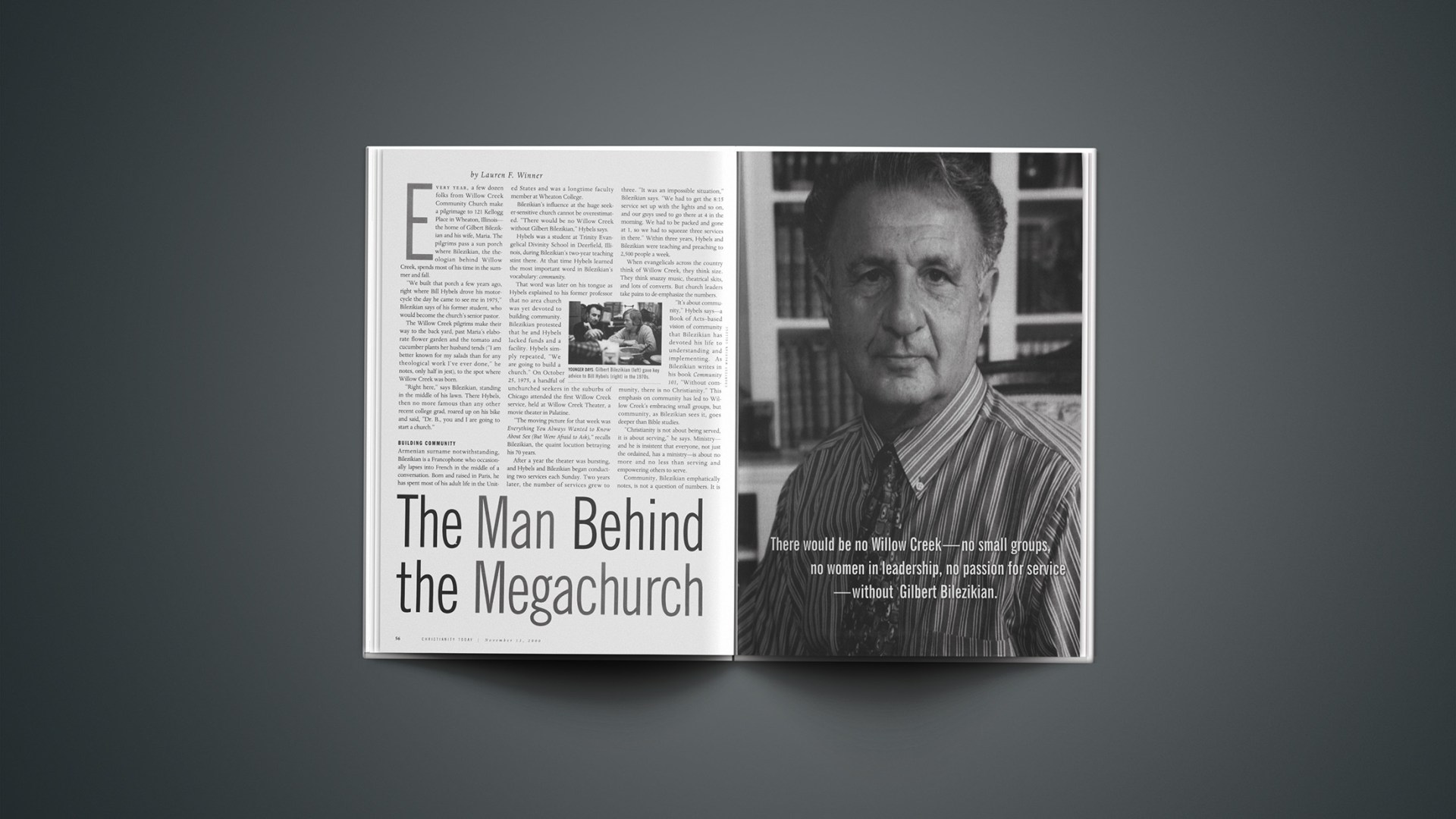

Armenian surname notwithstanding, Bilezikian is a Francophone who occasionally lapses into French in the middle of a conversation. Born and raised in Paris, he has spent most of his adult life in the United States and was a longtime faculty member at Wheaton College.

Bilezikian’s influence at the huge seeker-sensitive church cannot be overestimated. “There would be no Willow Creek without Gilbert Bilezikian,” Hybels says.

Hybels was a student at Trinity Evangelical Divinity School in Deerfield, Illinois, during Bilezikian’s two-year teaching stint there. At that time Hybels learned the most important word in Bilezikian’s vocabulary: community.

That word was later on his tongue as Hybels explained to his former professor that no area church was yet devoted to building community. Bilezikian protested that he and Hybels lacked funds and a facility. Hybels simply repeated, “We are going to build a church.” On October 25, 1975, a handful of unchurched seekers in the suburbs of Chicago attended the first Willow Creek service, held at Willow Creek Theater, a movie theater in Palatine.

“The moving picture for that week was Everything You Always Wanted to Know About Sex (But Were Afraid to Ask),” recalls Bilezikian, the quaint locution betraying his 70 years.

After a year the theater was bursting, and Hybels and Bilezikian began conducting two services each Sunday. Two years later, the number of services grew to three. “It was an impossible situation,” Bilezikian says. “We had to get the 8:15 service set up with the lights and so on, and our guys used to go there at 4 in the morning. We had to be packed and gone at 1, so we had to squeeze three services in there.” Within three years, Hybels and Bilezikian were teaching and preaching to 2,500 people a week.

When evangelicals across the country think of Willow Creek, they think size. They think snazzy music, theatrical skits, and lots of converts. But church leaders take pains to de-emphasize the numbers.

“It’s about community,” Hybels says—a Book of Acts–based vision of community that Bilezikian has devoted his life to understanding and implementing. As Bilezikian writes in his book Community 101, “Without community, there is no Christianity.” This emphasis on community has led to Willow Creek’s embracing small groups, but community, as Bilezikian sees it, goes deeper than Bible studies.

“Christianity is not about being served, it is about serving,” he says. Ministry—and he is insistent that everyone, not just the ordained, has a ministry—is about no more and no less than serving and empowering others to serve.

Community, Bilezikian emphatically notes, is not a question of numbers. It is qualitative rather than quantitative. You can have community with three or 3,000.

Just what does community look like? Bilezikian says there are two main components. The first is servanthood. Ask those who know Bilezikian, and they will tell you that he practices what he preaches—he is wont to wash coffee cups and other dishes even when there are others around who are paid to do so. John Ortberg, one of Willow Creek’s teaching pastors, says that understanding Bilezikian means understanding his zeal for servanthood.

“Once we were at the Wheaton College cafeteria, and a kid dropped an apple on the ground and left it there,” he says. “Gil was so bothered that he leaned down and picked it up. The kid assumed he was a janitor, but Gil the eminent theologian didn’t mind.”

Hybels tells a similar story, this one set in Germany during a Willow Creek seminar. Bilezikian had taught all day after spending the night on an airplane. But he was ready when Hybels realized they needed to move all their equipment from one auditorium to another.

“I called for volunteers to help, and there was Gil, then in his mid-60s, taking off his jacket, rolling up his sleeves, and carrying lighting equipment like a high-school kid,” Hybels says.

A woman’s place

Most Christians will not argue with the primacy of servanthood. But out of Bilezikian’s concept of community has come another teaching, more controversial in its outworking: gender equality.

“I am not a feminist,” Bilezikian says. “Feminism is about power, and I am about servanthood. I’m not pursuing equality for its own sake; there is no mandate in the Bible to pursue equality. But there is a mandate to establish community. And authentic community necessarily implies full participation of women and men on the basis of spiritual gifts, not on the basis of sex.”

Bilezikian was one of the proponents of mutual submission long before it was fashionable in evangelical circles. “Mutual submission is a biblical concept,” he says. “The words are used specifically in a number of texts but especially in Ephesians 5:21, where it says be mutually submitted to each other.” The wife submits to the husband just as the church does to Christ, but there is a reciprocity, he says: “Christ submits himself in-depth to the church, and the church submits itself in service to Christ. But then the husband is also under submission because he has to love his wife as he loves himself, even to the point of self-sacrifice as Christ loved the church.”

Both men and women, then, desire to serve the other rather than to control the other, Bilezikian says.

“Our natural tendency is to compete or take advantage of,” he says. “The Bible says lay down your arms and instead extend your hands toward each other to help each other and to support each other; and for the relationship to be one of partnership and mutuality rather than one of hierarchy.”

Bilezikian says he tries to live out these principles in his marriage, and they are also evident at his church. Not everyone at Willow Creek initially agreed with Bilezikian’s position on women’s ministry: among others, Hybels himself taught the traditional view of male headship. After months of study and debate, the church decided that it would support women in any position of leadership—teacher, preacher, elder.

Bilezikian says that if the group had come to the opposite conclusion, there would be no Willow Creek Community Church. “Among the elders there has been from the beginning a bunch of very strong women—very sharp, intelligent women who I think have helped us shape the church. If we had gone the other way, I probably would not have stayed at the church. But then there would have been not much to stay for.”

The church has garnered some criticism because it requires that a potential member be able to “joyfully sit under the teaching of women teachers at Willow Creek” and “joyfully submit to the leadership of women in various leadership positions at Willow Creek” before joining the church. Laurie Pederson, who was a student of Bilezikian’s at Wheaton and one of the first elders at Willow Creek, thinks the criticisms are off-base.

“That women are in positions of leadership is an essential part of Willow Creek church,” she says. “We don’t say that all Christians have to agree with us. We just think that if you can’t embrace this teaching, practically speaking, you’d probably be happier at some other church.”

Handling critics

Bilezikian has inspired a lot of ire among Christians who disagree with him about gender roles. He still receives hate mail about his book Beyond Sex Roles (1985), which argues that before the Fall there were no gender roles, which were introduced as a result of sin and God’s curse.

In sending his Son to Earth, God is “reclaim[ing] human beings so that his original creation purposes could be worked out in their lives and in their corporate destiny,” Bilezikian writes.

Through a careful reading of Scripture, Bilezikian argues that “secular socializations regarding sex roles,” whereby men are cut out for certain tasks and women for others, have no place in a Christian community. Some, though, consider his teachings misguided. Tim Bayly of the Council for Biblical Manhood and Womanhood believes that male headship starts from the very moment of creation, as Adam was created before Eve.

Wayne Grudem, another biblical scholar who advocates male headship, charges that Bilezikian is responsible not just for the collapse of gender roles in the church but also for popularizing an approach to Scripture that will have even more dire consequences.

“Beyond Sex Roles has regrettably been widely influential,” Grudem says. “Gilbert Bilezikian has been one of the three or four most influential egalitarian scholars.”

It is a slippery slope, Grudem says, from gender egalitarianism to accepting homosexuality. “Over the course of decades, the methods of interpreting Scripture by which Paul’s teachings on women and men are culturally relative will likely be used to make other issues culturally relative.”

Bilezikian has taken pains to distance himself from legitimizing homosexuality, as have other egalitarian scholars. The kingdom of God has been built up through thousands of people coming to Christ through Willow Creek, Grudem says, “but I disagree with Willow Creek’s stand on [egalitarianism].”

Egalitarian gallant

Walking the halls of Willow Creek with Bilezikian is like walking through a shopping mall with a movie star. People stare, and he can’t complete a sentence without someone waving and calling, “Hey, Dr. B.!” Women of 83 and girls of 6 rush up to him, knowing he will kiss their hand and compliment their ravishing beauty.

Bilezikian chalks up his effusive appreciation of female beauty to his mother’s early death. “I idealized her. As a young man, I was always searching for that elusive perfection in womanhood, which was such an enigma, for someone growing up with no sisters and no mother.”

To some degree, the enigma of womanhood is still with him—he can’t figure out why one of his daughters got a tattoo on her derri#232;re.

“Women at Willow Creek fall in love with him all the time,” Ortberg says. “He has legions of female followers. He manages to be thoroughly egalitarian and thoroughly French at the same time.”

Besides his French eye for beauty, Bilezikian also enjoys a Frenchman’s palate. He continues to serve guests p#226;t#232;, although his cardiologist has forbidden him to partake of it. He enjoys a glass of red wine with his meal, though his fondness for vino presented a problem when he began at Wheaton, which requires faculty members to sign a pledge to swear off alcohol. After a few weeks of devout teetotaling, Bilezikian presented the Wheaton administration with a letter from his doctor declaring that the biblical scholar required one glass of wine a day.

Childhood and Hitler

One could speculate that Bilezikian’s obsession with community is rooted in the societal destruction he witnessed as a child. His parents fled Armenia during the genocide of 1915.

Says Bilezikian: “When Hitler was developing his programs of ethnic cleansing, some of his advisers said, ‘You won’t be able to get away with this,’ and Hitler replied, ‘Who remembers the Armenians today?’ ” Bilezikian remembers the Armenians and the Jews. Standing in his kitchen with tears streaming down wrinkled cheeks, Bilezikian recounts the Holocaust’s descent on Paris, when he was 11.

“Every day I walked to school, and on my way to school, I met one neighborhood boy, and a few blocks later, a second neighborhood boy. Every day we walked to school to gether. One day, one of my friends wasn’t there. A second day he wasn’t there. That afternoon, we thought maybe he was sick. We thought we’d go up to his apartment to say hello.

“We got to his apartment and there was a big red ribbon with a swastika pasted across the doorframe. I never saw him again.”

The son of Armenian refugees who grew up in occupied France, Bilezikian never intended to settle in America—but a series of providential events eventually brought him not only to the United States but into contact with Hybels.

From boxer to medic

As a young man, he had a promising future in Paris in an unlikely field: pugilism. But he was converted at a Salvation Army meeting, and Bilezikian traded in his boxing gloves for the Bible. He planned to study theology in France, but when his first love died suddenly, Bilezikian was plunged into despair. “I had to leave France. I had to leave everything I knew.”

He had an uncle in Boston, so Bilezikian headed for Gordon–Conwell Theological Seminary. He stayed to study for his doctorate, too, earning his Ph.D. from Boston University, and then was called back to France to serve in the army. Before he was through, Bilezikian had done several reluctant stints with the French military.

“It is hard to imagine him in the army,” says Mark Discher, a Wheaton graduate and onetime Willow Creek employee. “Anyone who knows him knows that he is a gentle, kind, meek, almost placid, pacifistic in nature kind of individual.”

Even Bilezikian’s war stories reflect his pacifism. Called to his superior’s quarters during boot camp, Bilezikian learned that he was to be promoted to officer. The army was looking for educated men. “I turned down that promotion,” he says. “I knew it would get me out of the grueling drudgery of boot camp, it would mean an easier army life, but I told them I could not be responsible for other men killing. I could only be responsible for myself.”

Later he was sent to a hospital in Algeria. “They told me they needed doctors, and they saw that I had a doctorate. When I explained that my doctorate was in theology, the officer said, ‘I don’t know what theology is, but if it’s a disease, we’ve got it here.’ “

Bilezikian’s superior at the field hospital was a wonderful man who was usually drunk, he says. During sober moments, he showed Bilezikian how to bandage and cut, disinfect, and medicate. While the medical doctor was sleeping off his hangovers, the theology doctor was healing soldiers. “So, God sent me there for a purpose,” Bilezikian says.

After teaching for a few years in France, Bilezikian returned to upstate New York, where he pastored a church for two years before plunging back into the academic life. From there he went to Wheaton, and from Wheaton to Lebanon, where he became the president of a university.

“I was meant to be there for six or seven years, but I had to come back after two.” His son Lionel needed special medical attention. Bilezikian has never blamed God for his son’s medical problems, but he has praised God for bringing goodness out of pain. It was then that Bilezikian secured a post at Trinity.

“I was only there for two years—the very two years Hybels was there as a transfer student,” Bilezikian says. “So God builds great things out of suffering. Lionel has suffered because of his health, but out of that suffering God built the relationship between Hybels and me, and out of that he built Willow Creek.”

Lauren Winner is a staff writer for CT.

Related Elsewhere

Visit the Willow Creek Community Church homepage.

One of Willow Creek’s largest controversies has been its endorsement of women as elders and pastors. To learn more about Bilezikian’s influence on the gender equality debate within evangelicalism read World‘s “Femme Fatale ” or visit the Christians for Biblical Equality homepage.

Gilbert Bilezikian’s books are available from Worthybooks.com: Beyond Sex Roles: A Guide for the Study of Female Roles in the Bible, Christianity 101: Your Guide to Eight Basic Christian Beliefs, and Community 101: Reclaiming the Church as a Community of Oneness.

Other articles about Willow Creek’s growth and influence include:

Willow Creek’s growth came by word-of-mouth, not advertising —The Baptist Standard (April 17, 2000)

Network’s management style puts an unlikely mix of congregations on the cutting edge —The Dallas Morning News (June 20, 1998)

Commonly Asked Questions About Willow Creek Community Church —The Atlantic Monthly

Previous Christianity Today articles about Willow Creek include:

Repentance or Propaganda? | At Willow Creek conference, President Clinton reviews his moral failures, details his spiritual recovery. (Aug. 11, 2000)

Willow Creek Church Readies for Megagrowth | New auditorium will seat 7,000. (May 5, 2000)

Willow Creek’s Methods Gain German Following | (April 26, 1999)

Hybels Does Hamburg | Will Willow Creek’s model float in Germany? (January 6, 1997)

Copyright © 2000 Christianity Today. Click for reprint information.